How informed or uninformed are bank depositors in a banking crisis? Can depositors anticipate which banks will fail? Understanding the behavior of depositors in financial crises is key to evaluating the policy measures, such as deposit insurance, designed to prevent them. But this is difficult in modern settings. The fact that bank runs are rare and deposit insurance universal implies that it is rare to be able to observe how depositors would behave in absence of the policy. Hence, as empiricists, we are lacking the counterfactual of depositor behavior during a run that is undistorted by the policy. In this blog post and the staff report on which it is based, we go back in history and study a bank run that took place in Germany in 1931 in the absence of deposit insurance for insight.

The German Crisis of 1931

We study the run on the German banks in spring of 1931, which occurred at the height of the Great Depression in Europe. It remains one of the most prominent system-wide bank runs in history.

This setting is ideal to study depositor behavior for three reasons. First, the German banking system at the time had no deposit insurance. Moreover, it was generally lightly regulated and there were no capital or liquidity regulations imposed on banks. Consequently, bank creditors had reason to believe that they would lose money if their bank defaulted, unlike the contemporary banking system in which many creditors have access to deposit insurance. Second, because government interventions were limited, the crisis featured many bank failures. Around 15 of more than 120 banks in our sample fail during or after the run. Third, we digitize granular balance sheets for a representative part of the banking system that are available at a monthly frequency, unlike most contemporary banking data—such as the Federal Reserve’s FR Y-9C—that are only available at a quarterly frequency. The availability of historical data at the monthly frequency allows us to better study the dynamics of the run than existing studies.

Taken together, these three facts create conditions for us to see into the evolution of deposits in failing and surviving banks and ultimately allow us to answer the question: Which depositors can tell which banks will fail?

Can Depositors Tell Which Banks Will Fail?

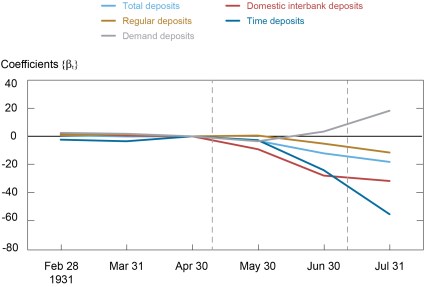

The chart below plots the evolution of different types of bank deposits for the time just before and during the run. We find that throughout the run, which lasts around two months and ends with the declaration of a banking holiday (more details on the exact sequence of events can be found in the paper), the German banking system loses around 20 percent of its overall deposit funding. Importantly, the run is centered around a contraction of interbank deposits (deposits that domestic banks held with other banks). Interbank deposits fall by around 30 percent on average. Regular deposits (retail and non-financial wholesale deposits) fall by around 18 percent on average. Further, demand deposits increase towards the end of the run while the withdrawals are mostly centered around the outflow of time deposits. Demand deposits increase rather than decrease as depositors that do not withdraw from the banking system are increasingly taking a cautious stance and convert their time deposits into demand deposits in preparation of withdrawing their funds.

Aggregate Deposit Flows Relative to April 1931

Source: Blickle, Brunnermeier, and Luck. 2022. “Who Can Tell Which Banks Will Fail?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 1005 (February).

Notes: The chart depicts aggregate deposit flows in the German banking System. We show flows in total deposits as well as regular, domestic interbank, demand, and time (wholesale) deposits separately. All flows are indexed to the last pre-crisis month (April 1931). The first vertical line marks the failure of the Creditanstalt on May 11, 1931, and the start of the crisis, and the second marks the failure of the Danatbank at the height of the crisis on July 13, 1931.

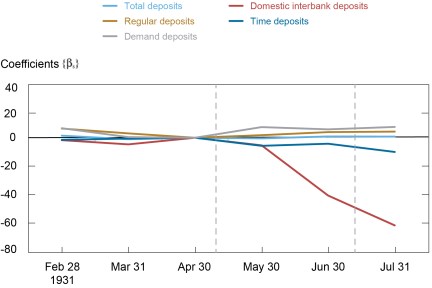

We next analyze whether there are differences in the deposit flows for banks that failed or survived after the run. In the next chart, we plot the difference in deposits between failing and surviving banks in the month before and during the run. Strikingly, irrespective of whether a bank fails or not, deposits fall by the same amount. That is, there is no difference in total deposit outflows between failing and surviving banks. This implies that, on average, depositors are seemingly unable to successfully identify which banks are likely to fail.

Deposit Flows in Failing and Surviving Banks

Source: Blickle, Brunnermeier, and Luck. 2022. “Who Can Tell Which Banks Will Fail?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 1005 (February).

Notes: This chart depicts relative deposit flows in German banks, comparing failed to non-failing banks. We regress bank deposits in a given month on a number of bank characteristics and an indicator denoting whether the bank eventually fails. The plot shows the coefficient on the indicator variable, which represents the degree to which failed banks—after accounting for a host of controls—experience different deposit flows from non-failed banks. We show flows in total deposits as well as regular, domestic interbank, demand, and time (wholesale) deposits separately. All flows are indexed to the last pre-crisis month (April 1931). The first vertical line marks the failure of the Creditanstalt and the start of the crisis, and the second marks the failure of the Danatbank at the height of the crisis.

However, the behavior of the average depositor obscures the distinct behaviors of different types of depositors. As indicated above, our data allow us to distinguish between regular deposits on the one hand and interbank deposits on the other hand. We find that regular depositors do not discriminate between failing and surviving banks. There is no difference in regular deposit flows prior to the run compared with after as seen by the gold-colored line in the first chart above. If at all, regular deposits fall by less than other types of deposits in failing banks.

By contrast, interbank depositors identify failing banks with a high degree of precision: failing banks start to lose access to the interbank market early in the run, and by the time the banking system collapses, they are essentially shut out of the interbank market (see the red line in the second chart). However, because interbank deposits are a small share of overall deposit funding, the sum of all deposits falls by about the same in failing and non-failing banks over the period.

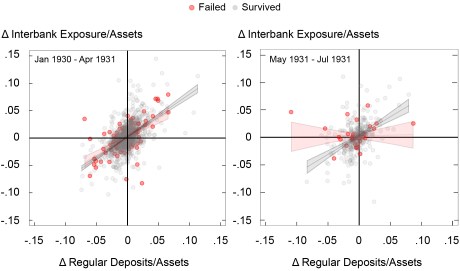

Furthermore, banks do not hoard liquid funds during the run. Rather, they continue to lend to other banks —but only to those that survive. This finding is illustrated in the next chart, which correlates the change in deposits over a month for a bank (x-axis) with a bank’s change in net borrowing/lending in the interbank market (y-axis). In a functioning interbank market, this correlation is close to one: banks with deposit outflows are borrowing in the interbank market from banks with deposit inflows. Splitting the sample into those banks that fail and those that survive, the left panel shows that the interbank market works for both types of banks prior to the run, as seen by the positive correlation. In the right panel, when studying the same correlation during the run, we find that the correlation is low for failing banks, but it is almost unchanged from the pre-run period for surviving banks. Hence, the interbank market, while collapsing for failing banks, remains functioning during times of high financial distress for surviving banks. We interpret this as evidence that banks not only identify which banks will fail, they are also very confident about which banks will survive.

Interbank Market Collapses for Failing Banks in the Crisis

Source: Blickle, Brunnermeier, and Luck. 2022. “Who Can Tell Which Banks Will Fail?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 1005 (February).

Notes: This chart depicts the correlation between changes in regular (non-interbank) deposits normalized by total assets and interbank exposure (defined as (Interbank Lending–Interbank Deposits)/Assets). The left panel shows the pre-crisis relationship where all banks have similar access to the interbank market. The right panel shows that the relationship breaks down for failing banks in the crisis.

What Do We Learn?

Taken together, our findings suggest that there is a considerable heterogeneity in the way different types of depositors behave in a financial panic. Regular depositors are strikingly uninformed about the likelihood of their bank to survive the run even though they are at high risk of realizing losses if their banks fail. Banks themselves, however, seem to have very precise information about which banks will fail and which will survive the run.

Why are these findings important? Understanding the roles of depositors in bank runs is key to evaluating policies designed to prevent runs, such as deposit insurance. Deposit insurance is arguably one of the most universal/pervasive forms of government intervention in the modern financial system. Almost one third of all liabilities (and almost two thirds of all deposits) for large U.S. bank holdings companies are insured by the FDIC. In theory, however, we know that deposit insurance can have positive and negative effects. On the one hand, such insurance is desirable if it prevents self-fulfilling and inefficient banking panics. On the other hand, it is not desirable if it amplifies a moral hazard and ultimately leads to bank managers taking more and undesirable types of risk. Given that theories of banking are not entirely clear on whether it is a useful policy, it becomes crucial to study the subject empirically.

While it is important to be cautious when generalizing from historical experience—after all the U.S. banking system is quite different than the German banking system in 1931—a logical conclusion from our evidence is that the potential for a deposit insurance scheme, which targets regular depositors, to undermine the disciplining effect of short-term debt is somewhat limited. We find that retail and non-financial wholesale depositors—even if uninsured—may not run at all, and to the extent that they do run, they don’t discriminate between banks by their likelihood of failure. Thus, retail-depositor oriented insurance schemes do not undermine discipline or exacerbate moral hazard. In the case of the German Crisis of 1931, a deposit insurance scheme for retail deposit accounts would have plausibly only prevented withdrawals from those depositors that were unable to distinguish between weak and strong banks and thus it is unlikely to have undermined depositor discipline.

While interbank markets are typically considered to be valuable, as they allow banks to insure against liquidity shocks, our evidence hence suggests that the existence of a functioning interbank market can also be valuable for its informational content. Thus, it may also be beneficial to maintain and promote active and functioning interbank markets to avoid losing this valuable information.

Kristian Blickle is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Markus Brunnermeier is a professor of economics at Princeton University.

Stephan Luck is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics