The first post of this series found that small businesses owned by people of color are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters. In this post, we focus on the aftermath of disasters, and examine disparities in the ability of firms to reopen their businesses and access disaster relief. Our results indicate that Black-owned firms are more likely to remain closed for longer periods and face greater difficulties in obtaining the immediate relief needed to cope with a natural disaster.

How Often and How Long Do Small Businesses Close After Disasters?

The Federal Reserve’s 2021 Small Business Credit Survey (SBCS) asked disaster-affected firms: “Did your business temporarily close because of this natural disaster?” Amongst firms that responded yes, the survey also asked them to estimate the length of time for which they were temporarily closed. These responses likely represent lower bounds for closure since a firm that was closed temporarily at the time of survey completion may have ended up remaining closed for longer than reported.

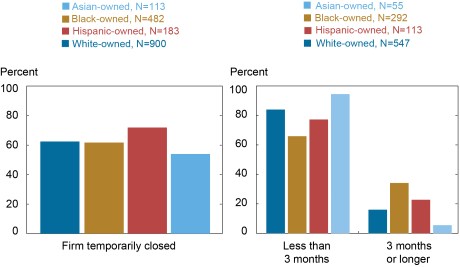

Sixty-three percent of small businesses that reported natural disaster-related losses were forced to close temporarily. Although the fraction of firms that temporarily closed is relatively similar between Black- and white-owned firms, Hispanic-owned firms were more likely to be forced to temporarily shut their doors (see left panel of the chart below). There are also pronounced disparities in the length of closures for impacted firms (see right panel of the chart below). For example, 34 percent of Black-owned firms and 23 percent of Hispanic-owned firms were forced to keep their doors shut for greater than three months as compared to only 16 percent of white-owned and 6 percent of Asian-owned small businesses.

Part of this disparity may be explained by the finding in our previous post that losses from natural disasters make up a greater share of total revenue for firms owned by people of color. More generally, the severity of a disaster’s impact can be compounded by existing disparities in access to financial resources available to business owners prior to a disaster (for example, because Black and Hispanic small business owners have a lower level of starting wealth).

Firms Owned by People of Color Remain Closed for Longer

Notes: The left panel includes only firms that reported disaster-related losses. For respondents in each race/ethnicity category, the bars plot the percentage of firms that responded yes to the question: “Did your business temporarily close because of this natural disaster?” The panel on the right further limits the sample to firms that temporarily closed because of a natural disaster. For each race/ethnicity category this panel shows the percentage of firms that were closed for the length indicated on the x-axis at the time of survey completion. A firm is considered Black-, Hispanic-, or Asian-owned if at least 51 percent of the firm’s equity stake is held by owners identifying with the group. A firm is defined as white-owned if at least 50 percent of the firm’s equity stake is held by non-Hispanic white owners. Race/ethnicity categories are not mutually exclusive. An observation is excluded from the sample if it is missing a response to the question or if the owner’s race is not observed. The sample pools employer and nonemployer firms. Responses by employer and nonemployer firms are weighted separately on a variety of firm characteristics to match the national population of employer and nonemployer firms, respectively. To construct a pooled weight, we use the employer (nonemployer) weight if the firm is an employer (nonemployer). Fielded September-November 2021.

What Sources Can Small Businesses Turn to for Relief?

In the aftermath of a disaster, small businesses experience an increase in demand for funding to replace damaged properties and replace lost revenues while they are temporarily closed or operating at reduced capacity. Immediately after a natural hazard, firms can tap into existing cash reserves or emergency funds. According to research by the JPMorgan Chase Institute (JPMCI), the median small business holds a cash buffer large enough to support twenty-seven days of their typical outflows. However, this number does not account for funds needed to repair or replace property and physical assets damaged in a disaster. Moreover, firms in labor intensive and low-wage industries have fewer buffer days relative to high-technology or professional service enterprises.

Property insurance can help firms repair and replace direct physical damages, and business disruption insurance can cover lost incomes and operating expenses that continue while the business is closed. Previous research has documented that only 30-40 percent of small businesses have business disruption insurance.

Firms whose losses are not fully covered by insurance can turn to funding from the federal government if located in a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)-designated disaster area. The Small Business Association (SBA) provides long-term, low-interest loans to repair or replace damaged property. The SBA also offers Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDLs) of up to $2 million to meet expenses the business would have paid if the disaster had not occurred. FEMA provides recovery grants to small businesses, but only through referral upon completion of the SBA loan application. State and local relief programs intended for small businesses are limited, and state governments often appropriate emergency funds only after a disaster declaration is made, which delays immediate assistance.

Beyond these sources, firms with additional need can take on debt, loans, or lines of credit from banks, online lenders, or public private partnerships, and natural disasters are associated with higher demand for credit from such lenders. Securing a loan or line of credit of moderate size requires collateral, but a disaster can limit the ability of firm-owners to pledge their homes that are damaged in disasters.

How Do Funding Sources Vary Across Owner Race and Ethnicity?

More limited access to financial relief following a disaster may drive the longer closure periods for small businesses owned by people of color. For example, lower home values can make it relatively more difficult for them to put up adequate collateral for loans. And disparities in the allocation of government aid to affected firms may make it more difficult for firms owned by people of color to reopen their doors and recover revenues following a disaster. However, if these firms apply for government aid at a high rate, their take-up of these loans could be substantial even with low approval rates.

In 2021, the SBCS asked respondents that reported disaster losses to indicate the source(s) that they relied on to cope with their losses. Firms could select from multiple options as shown in the table below. A higher fraction of white-owned firms (12 percent) relied on disaster insurance funds compared to Black-owned firms (6 percent). This gap may be driven by a lower fraction of firms owned by people of color possessing insurance; younger, smaller, and financially constrained firms are less likely to insure—a profile that often fits firms owned by people of color. Further, conditional on having insurance, agencies may be less likely to pay claims of businesses owned by people of color, and so the latter may rely less on this source of funding.

Disparities in Funding Sources to Assist with Disaster Relief

| Funding Source(s) Relied On: | (1) All | (2) White | Race/Ethnicity (3) Black | (4) Hispanic | (5) Asian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.17 |

| Federal disaster relief (e.g., FEMA, SBA) | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.25 |

| State/local government disaster relief funds | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.31 |

| Donations, crowdfunding, or nonprofit grants | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| Debt/loans (other than gov’t loans) | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.27 |

| Other | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Did not rely on external funds | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.35 |

| Observations | 1,687 | 902 | 469 | 182 | 112 |

Notes: This table includes only firms that reported disaster-related losses. The SBCS asks these firms: “Which of the following sources of funding did your business rely on to cope with these losses? Select all that apply.” The options are listed in the left column of the table. For each race/ethnicity category, the table reports the fraction of firms that relied on a particular source of funding. The columns do not sum to one because survey respondents had the option to select multiple sources. A firm is considered Black-, Hispanic- , or Asian-owned if at least 51 percent of the firm’s equity stake is held by owners identifying with the group. A firm is defined as white-owned if at least 50 percent of the firm’s equity stake is held by non-Hispanic white owners. Race/ethnicity categories are not mutually exclusive. An observation is excluded from the sample if it is missing a response to the question or if the owner’s race is not observed. The sample pools employer and nonemployer firms. Responses by employer and nonemployer firms are weighted separately on a variety of firm characteristics to match the national population of employer and nonemployer firms, respectively. To construct a pooled weight, we use the employer (nonemployer) weight if the firm is an employer (nonemployer). Fielded September-November 2021.

Among disaster-affected firms, Black-owned businesses disproportionately relied on government programs from FEMA, the SBA, and other agencies: 22 percent of Black-owned firms relied on federal disaster relief funds, compared to only 13 percent of white-owned companies. Previous research and news reports have documented evidence of racial disparities in approvals of SBA disaster loans and FEMA disaster relief. Further, the SBA has acknowledged that in disaster loan approvals, they strongly consider credit scores that may be affected by biases in scoring models. Even among firms that ultimately receive federal relief, application and disbursement can occur with long delays, limiting their effectiveness right after a disaster when funding is most needed. Our results imply that firms owned by people of color apply for government aid at a greater rate so that they have a higher take-up of these loans, despite being approved at lower rates.

A slightly higher fraction of white-owned firms did not rely on any external relief to cope with disaster losses (see table above), consistent with our finding in the first post of this series that disaster-related losses make up a smaller share of total revenues for white-owned firms. This gap could also be explained by differences in the size of firms’ cash reserves as, according to research by the JPMorgan Chase Institute, small businesses in majority-Black and majority Hispanic communities have fewer cash buffer days relative to majority-white areas.

Final Words

Relative to white-owned firms, Black-owned businesses are more likely to remain closed for longer and rely disproportionately on less immediate forms of relief funding. These results underscore the importance of accessing affordable relief after disasters to businesses owned by people of color.

Recently, state and local governments have established partnerships with the private sector to make disaster relief more accessible. For example, the New York Forward Loan Fund leveraged public funds with private dollars to provide low-interest working capital loans to help small businesses and non-profits—especially firms that typically lack access to credit—cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, the California Rebuilding Fund (CARF) aggregated funding from private, philanthropic, and public sector sources to help small business reopen and recover during the pandemic. The fund dispersed loans through community development financial institutions (CDFIs) that have experience working with traditionally underserved borrowers as well as Fintechs. Expanding these approaches to include disaster relief may enable vulnerable businesses to access the funding needed to reopen their doors and rebuild their revenues following disasters.

Martin Hiti was a summer research intern in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Claire Kramer Mills is a Communication Development Research Manager in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Communications and Outreach Group.

Asani Sarkar is a financial research advisor in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Martin Hiti, Claire Kramer Mills, and Asani Sarkar, “Small Business Recovery after Natural Disasters,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, September 6, 2022, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/09/small-business-recovery-after-natural-disasters/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics