The sharp slowdown in China’s property sector has reignited debate over the country’s future role as a net provider of savings to the global economy. The debate revolves around whether a sustained decline in property investment will spur a long-term increase in China’s current account surplus, given the country’s high savings rate. However, China’s rapidly aging population presents opposing forces that complicate this story. The shift of a large share of its population from working life to retirement will reduce savings supply even as a shrinking labor force will reduce investment demand. In this post, we focus on the demographic part of the story and find that this force will exert considerable downward pressure on China’s current account surplus in coming years.

Secular Decline in China’s External Balance Upended by the Pandemic

The current account balance (CAB) is the broadest measure of a country’s trade balance, encompassing the balance on goods and services, net income from overseas investments, and net transfers. As an accounting identity, the CAB is also equal to the gap between domestic savings and domestic investment. A country with a CAB surplus, such as China, places its extra savings in foreign financial markets, making it a net lender to the rest of the world. A country with a CAB deficit, such as the U.S., relies on foreign savings to finance part of its investment spending, making it a net borrower from the rest of the world.

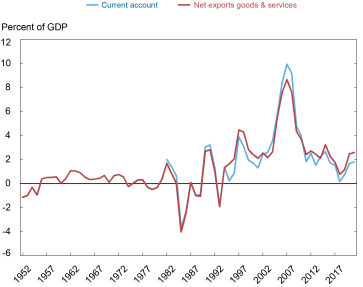

Before the pandemic China’s CAB had been in pronounced secular decline. The chart below shows the CAB and a close proxy as shares of GDP. The blue line is the CAB itself. The red line is the goods and services balance—the CAB excluding net income on overseas investments and net transfers—as this variable is available over a longer period.

China’s External Surplus Shrank Before Pandemic

China’s CAB remained close to balance prior to the early 1980s, due to the country being largely closed to foreign capital and goods markets. It became far more volatile when economic reforms were initiated during that decade. The picture changed still more dramatically after 1990 when China’s modern reform period began, and the country became more integrated into global capital and goods markets—a development exemplified by China’s admission into the WTO in 2001. China’s surplus peaked at 10 percent of GDP in 2007. It then began a precipitous decline, falling to below 1 percent of GDP by 2018, and leading many analysts to conclude that China was on the verge of flipping to becoming a deficit country.

The pandemic disrupted this trend. Domestic restrictions that suppressed household consumption, booming exports given China’s relatively early reopening, and plummeting outbound travel caused the CAB to swell to nearly 2 percent of GDP. The question we want to address is whether the pre-pandemic downward trend will resume once the dust settles. A strong argument can be made that China’s investment rate remains too high, and that falling investment will lead to larger surpluses. (Recall that the CAB is the difference between saving and investment.) At the same time, other forces could lead to lower household, corporate, and government savings.

Demographics Play an Important Role in the Balance Between Saving and Investment

Although a country’s savings-investment balance is influenced by a myriad of cyclical and policy factors, demographic factors can play a powerful role. The reason lies in the differential impact of population age structure on savings supply and investment demand. The intuition is as follows. Saving supply should be positively tied to the share of mature adults, through its connection with retirement needs. (Conversely, higher child or elderly population shares should be tied to lower savings, since these populations consume while generating little income.) Investment demand should be positively tied to the share of young adults, through its connection with labor force growth. (Conversely, negative demographic pressure on investment should emerge as the labor force ages and employment growth slows or even turns negative.) So long as a country is not closed to international capital flows—thus forcing the current account to remain balanced—differences in the timing of these saving and investment effects should lead to demographically-induced changes in the current account.

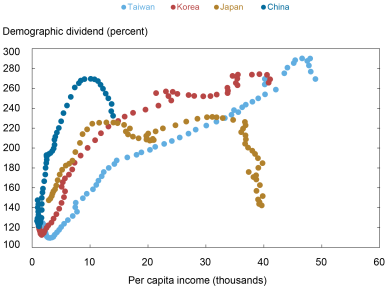

China’s demographic profile is undergoing profound change, with population aging occurring at a pace never before seen for a country at its income level. As shown in the chart below, China is now well past its peak “demographic dividend”—the ratio of its working-age population to its population of young and old dependents. Moreover, this is occurring at a much lower income level than observed in other countries. (In fact, China’s working-age population is declining not only as a percent of the total but also in absolute terms.) China’s outlier status is starkest at the upper tail of the age distribution. The share of China’s population over 65 years old is currently about 12 percent, even though China’s per capita income is only about one-half of Japan’s when it reached this milestone in 1989.

China’s Demographic Dividend Is Falling Despite Relatively Low Income Level

Notes: Demographic dividend is calculated as ratio of working population to young (0-14) and old population (65+). Per capita income shows income at purchasing power parity calculated from PWT. Years shown are 1950 – 2019 depending on availability.

Empirical Work Points to Downward Pressure on China’s External Balance

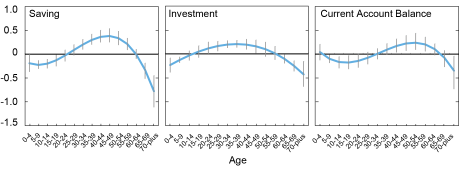

To check how the intuition holds up empirically, we follow the methodology of Higgins (1998). In particular, we estimate statistical models that treat savings, investment, and the CAB (measured as shares of GDP) as functions of the following explanatory variables: population age shares, productivity growth, the relative price of investment goods, and fixed country-specific characteristics. (Our data set is comprised of 142 countries and covers 1950 to 2019.) Our interest in this post is on the role played by the age structure variables.

The three panels in the chart below show the results of this analysis. Each panel shows the amount that saving, investment, and the CAB change, as a percent of GDP, per a 1 percentage point change in the share of the age cohort shown on the horizontal axis (holding other variables constant). Saving coefficients lift into positive territory around the early-30s, peak at around age 50, and then turn negative starting around 65. Those for investment turn positive and peak at a much earlier age, and then turn down and eventually becomes negative again. The net result of these shifts in saving and investment is demographic “pressure” on a country’s CAB, shown in the third panel. This pressure is initially negative for young populations, positive from around the mid- to late-30s, peaks in the mid-50s, and then turns down and is negative again in the older age cohorts.

Demographic Age Structure Has Differential Effects on Saving, Investment, and the Current Account

Note: Vertical lines show 1 standard deviation bootstrapped confidence intervals.

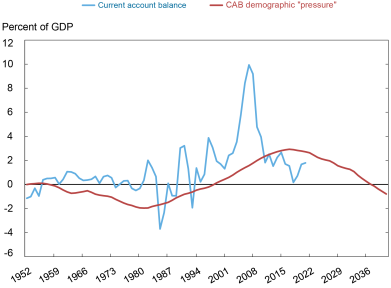

With these coefficients in hand, one can use historical data and projections of China’s population age distribution to get an idea of how this demographic pressure has influenced its CAB in the past, and how the CAB may evolve in coming decades. The chart below shows the current account balance alongside the pressure coming from demographics, both historically and in prospect using population projections from the United Nations. This pressure is calculated as a cumulative change since 1950.

Demographic Forces Will Reduce Surpluses

Note: The current account splices the goods and services balance from the national accounts prior to 1982 to the current account balance from the balance of payments from 1982 onward.

The chart shows that during the first thirty years demographic pressure on the CAB was increasingly negative. This suggests that China’s demographic profile would have been contributing to a CAB deficit during this period—and that the country could have benefited from a higher level of investment if it had been financially open and able to borrow from abroad. These demographic pressures hit an inflection point just as the reform period began in the early 1980s, and then went into overdrive beginning in the 1990s, contributing to the boom in CAB surpluses. Finally, demographic pressure hit a downward inflection point just before the pandemic. The downward weight on China’s external balance is projected to grow steadily more heavy over the next two decades. In fact, holding other influences constant and starting from its pre-pandemic level, changes in age structure could be enough to drag China’s CAB into deficit only a few years from now. If demography is destiny, the country’s days as a net lender to the rest of the world appear numbered.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the potential impact of demographic change on China’s current account should not be taken as a prediction. While the demographic coefficients in our statistical model appear estimated fairly precisely, they come with a margin of error that is transmitted into the projections.

More important, by design, our projections only consider the impact of demographic variables, abstracting from other cyclical and policy factors that can influence the CAB. Indeed, we began this post by referring to popular speculation that a real estate crash in China might cause a collapse in investment, swelling the CAB. A risk in the opposite direction comes from the country’s low ratio of household consumption to GDP. Measures to liberalize consumers’ access to credit markets could unlock suppressed household consumption, leading to a decline in savings and additional downward weight on the CAB. Equally, new restrictions on capital outflows could put a lid on the magnitude of future current account deficits.

The most we can say is that a continued role for China as net lender to the rest of the world would involve a long march up a steep demographic hill. Even if the authorities were to succeed in boosting birthrates—through relaxation of the one-child policy and other incentives, so far with little success—the resultant increase in children and young workers would put further downward pressure on the CAB relative to the estimates presented in this post.

Hunter L. Clark is an international policy advisor in International Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Matthew Higgins is an economic research advisor in International Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Hunter L. Clark and Matthew Higgins, “What Is the Outlook for China’s External Surplus?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 17, 2022, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/10/what-is-the-outlook-for-chinas-external-surplus/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics