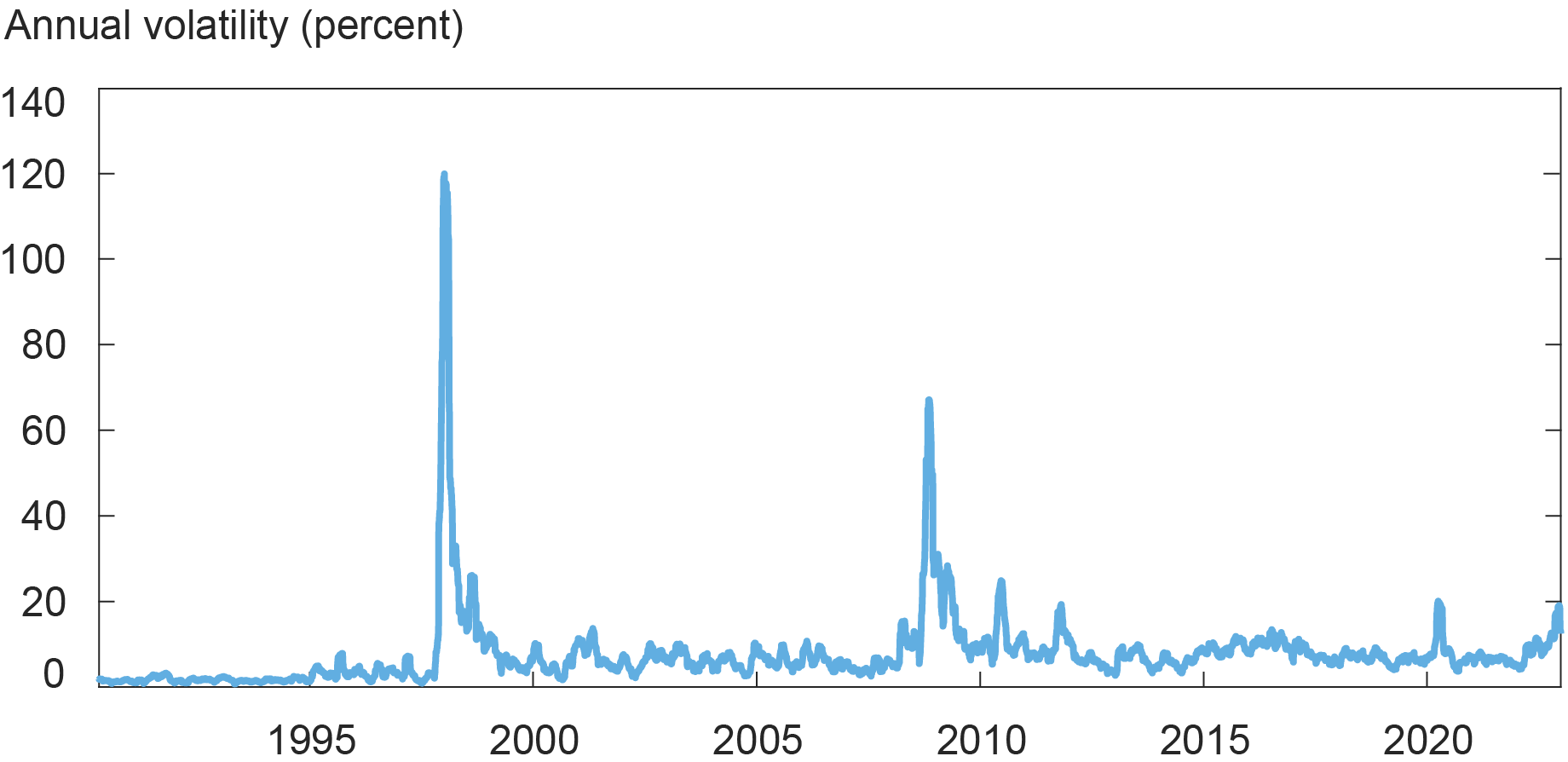

Foreign exchange derivatives (FXD) are a key tool for firms to hedge FX risk and are particularly important for exporting or importing firms in emerging markets. This is because FX volatility can be quite high—up to 120 percent per annum for some emerging market currencies during stress episodes—yet the vast majority of international trades, almost 90 percent, are invoiced in U.S. dollars (USD) or euros (EUR). When such hedging instruments are in short supply, what happens to firms’ real economic activities? In this post, based on my related Staff Report, I use hand-collected FXD contract-level data and exploit a quasi-natural experiment in South Korea to measure the real effects of hedging using FXD.

Economic Stress Can Trigger Massive Volatility for Emerging Market Currencies

Note: Chart shows the annualized thirty-day historical volatility of the USD-Korean won exchange rate.

Use of FX Derivatives Has Been Increasing

The use of FXD by corporates has been increasing in the past twenty years. In 2022, the notional value of outstanding over-the-counter FXD held by nonfinancial firms globally was approximately $15 trillion, a substantial increase from $5 trillion in 2000, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Despite the widespread use of FXDs and their potential importance, little is known about the effects of FXD hedging on international trade. This is likely due in part to identification challenges, most notably the endogeneity of corporate hedging decisions, as well as the difficulty of obtaining granular data on firms’ FXD holdings.

Real Effects of FX Derivatives Based on a Quasi-Natural Experiment

In 2010, South Korea introduced a macroprudential FX regulation that limits a bank’s ratio of FXD positions to equity capital. The regulation was designed to discourage risk-taking by financial intermediaries. Once implemented, the regulation was binding for some banks but not others, allowing me to compare the effects on these two groups of banks. By exploiting this quasi-natural experiment, I document that the regulation caused a shortage of FX hedging instruments, thus making it harder for exporters to hedge, which in turn resulted in a substantial reduction in exports, especially for small firms that relied heavily on FXD hedging.

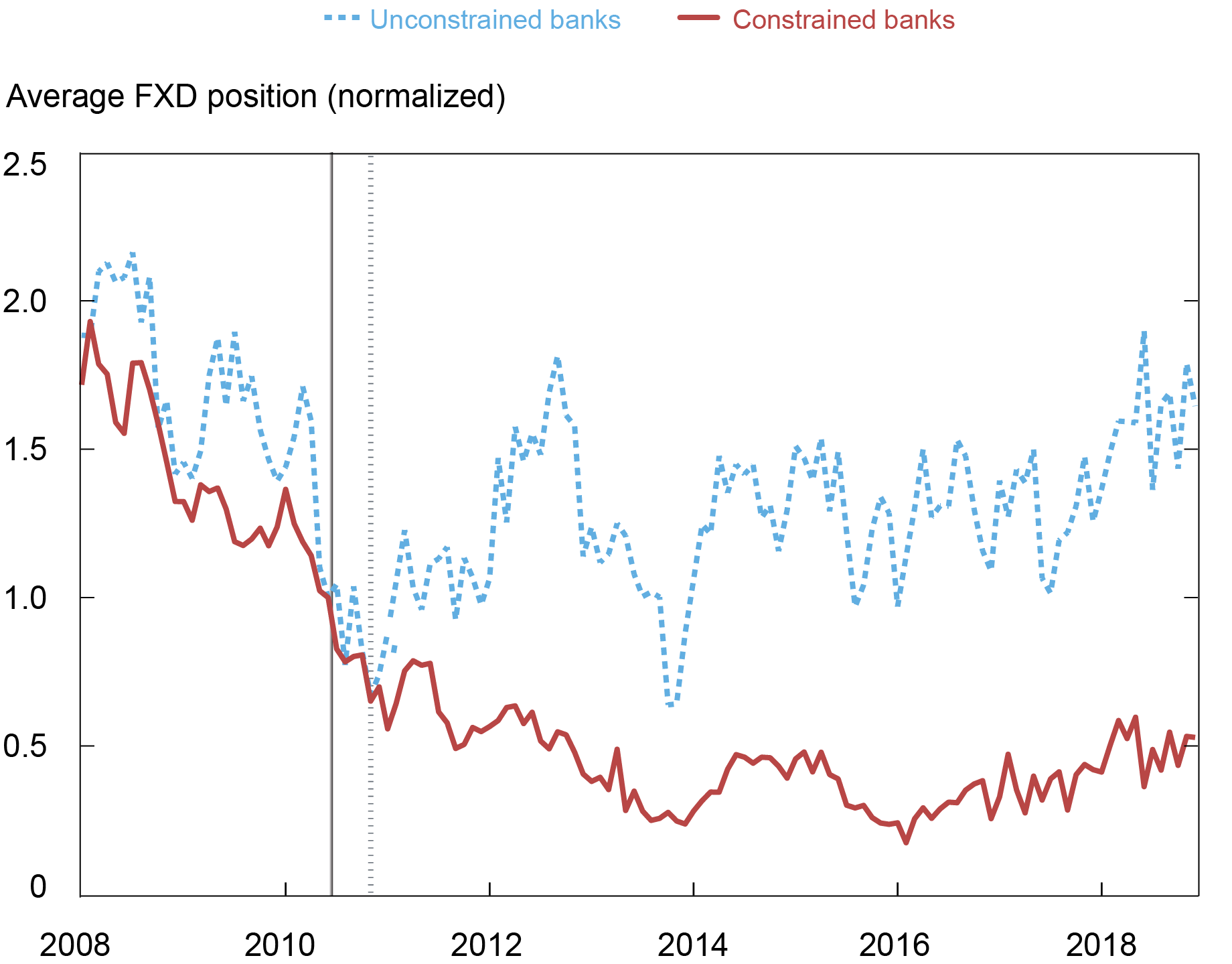

To measure the real effects of FXD hedging, I proceed in three steps. The first analysis is at the bank level. I define constrained (treatment) banks as those that needed to lower their FXD–capital ratio and unconstrained (control) banks as those that did not need to make such an adjustment when the regulation took effect. I show that, prior to the regulation, the FXD positions of the treatment and control banks moved in parallel. However, after the regulation (indicated by the first vertical line in the chart below), I find that the treatment banks reduced their FXD positions substantially compared to the control banks. This finding suggests that the regulation caused a reduction in the FXD position of banks.

Average FXD Position Held by Constrained Banks vs. Unconstrained Banks

Notes: Normalized FXD position of constrained (solid) and unconstrained (dotted) banks. FXD positions are normalized such that they are 1 at the imposition of the regulation. The vertical solid (dotted) lines indicate the announcement (effective) date of the regulation.

My analysis so far does not distinguish between demand and supply effects. In other words, the observed relative reduction in hedging by firms that traded with constrained banks could have been due to an increase in the hedging demand of firms that traded with unconstrained banks, as opposed to a decrease in the supply from constrained banks.

The second set of analyses aims at answering this question by isolating the two effects using FXD contract-level data. By comparing the contracts of firms that are within the same industry and have similar characteristics, I show that exporters’ hedging with constrained banks declined more than hedging with unconstrained banks by 47 percent, suggesting that the regulation caused a reduction in the supply of FXD by constrained banks.

The third set of analyses aims at estimating the effect on the real economy. By using the reduction in the supply of FXD as the exogenous shock, I examine whether it affected firm exports, which are the primary source of exposure to FX risk. I find that the firms that were more exposed to the shock reduced their exports by a greater amount after the shock. Moreover, the effect was concentrated on small exporters that were heavily reliant on FXD hedging. For a one-standard-deviation increase in a firm’s exposure to the regulatory shock transmitted by banks, export sales fell by 18.9 percent more for high-hedging firms than low-hedging firms.

Final Words

The findings in my paper have several important implications. First, they suggest that frictions in the FX market can affect international trade. Second, they imply that FXD is an essential hedging instrument for firms to manage their FX risks. Third, they indicate that macroprudential regulations on FXD, intended to address financial sector vulnerabilities, can have notable consequences for the nonfinancial sector.

Hyeyoon Jung is a financial research economist in Climate Risk Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Hyeyoon Jung, “Does Corporate Hedging of Foreign Exchange Risk Affect Real Economic Activity?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 12, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/04/does-corporate-hedging-of-foreign-exchange-risk-affect-real-economic-activity/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics