Proponents of narrow banking have argued that lender of last resort policies by central banks, along with deposit insurance and other government interventions in the money markets, are the primary causes of financial instability. However, as we show in this post, non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) triggered a financial crisis in 1772 even though the financial system at that time had few banks and deposits were not insured. NBFIs profited from funding risky, longer-dated assets using cheap short-term wholesale funding and, when they eventually failed, authorities felt compelled to rescue the financial system.

Non-Bank Financial Institutions in Late 18th Century Europe

In the mid-18th century, banks (as we know them today) were absent in Europe and so were bank regulators. Although deposit banking had been around for several centuries, deposit-takers were mere minnows compared to the largest merchant-financiers (except in Britain, where the banking sector had been growing for more than a decade). Instead, a “shadow bank” system developed, dominated by highly sophisticated NBFIs (specifically, the major merchant-financiers). The leading European firms, such as Hope & Co and Clifford & Sons (Clifford’s), provided an array of financial services that included the underwriting of debt securities, clearing of international payments, the custody of assets, and prime brokerage and insurance; they also invested in commodities and securities investments for their own accounts.

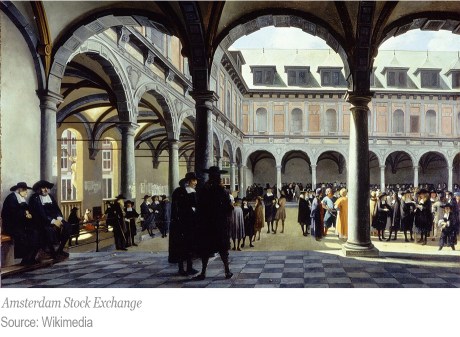

A three-pillar financial model of wholesale merchant-financiers, securities markets, and insurers evolved and continued to meet the needs of the mercantile economy until well into the 19th century. Active and deep financial markets developed, along with relatively open cross-border trade in financial services, and many of the activities performed by wholesale broker-dealer banks today (securities and commodity financing, prime brokerage, asset trading, securitization, and repo) flourished.

Credit Cycles in Late 18th Century Amsterdam

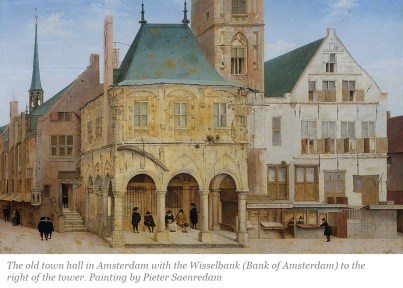

With its open economy, predictable legal framework, stable government finances, and leading role in the trade in precious metals, Amsterdam was the leading financial center in Europe for well over a century. The Amsterdam Wisselbank, although not a central bank in any modern sense, provided a stable and internationally accepted reserve currency for over 150 years—the bank guilder, typically referred to as the “florin.” The florin’s reserve currency status, along with a high level of savings, combined to make interest rates in the Netherlands notably lower than in the rest of Europe. By making time deposits at the Wisselbank, firms with coin collateral could access high-powered bank money paying as little as 0.5 percent. In the secured lending markets, Amsterdam wholesale firms could regularly borrow for 3.25 to 3.5 percent. As lending opportunities in nearby Britain and elsewhere offered returns of 5 percent or more, a large carry-trade developed between Amsterdam and London, with Dutch money being used to re-invest in the larger and faster-growing economy of Britain and that of its colonies.

As is often the case, cheap money resulted in risky behavior by large, highly leveraged wholesale players who would prove to be major vectors for a financial crisis, triggered in this instance by the battle for control of the English East India Company (EIC)—the largest trading firm of its day. Peace with France in 1763 had left the British militarily and economically dominant in the Indian sub-continent, generating expectations that the EIC would return large dividends to its shareholders, particularly after it secured tax and administrative control over the Bengal province in India. Much of the gains the firm won, however, disappeared into the pockets of company officials and so the expected peace dividend was not as large as some investors had hoped. Consequently, a group of rival EIC directors bid to take control of sufficient voting shares to control the company and increase the dividend.

Dutch merchant houses such as Clifford’s, Hope & Co. and others spotted an opportunity in this battle to act as something akin to contemporary prime brokers, lending money to leveraged speculators who could then offer their shares to the highest bidders. It was this lending activity that ultimately led to Clifford’s failure on December 27, 1772. With its syndicate partners, the Seppenwolde brothers and Abraham ter Borch, the firm had bet on a rise in the share price of the EIC. Collectively, the consortium controlled 5.6 percent of the EIC’s shares outstanding as well as a large holding in the equity of the Bank of England. But news out of India was not favorable to the profits of the EIC and the expected rise in its share price did not materialize.

At the time of its failure, Clifford’s had liabilities of 4.6 million florins, uncertain claims on its syndicate partners of 3.2 million florins and “good” assets of a little more than one million florins. As some contemporary sources pointed out, since the vast majority of exposures was to fellow members of a syndicate investment that had been struggling for well over a year, the firm may have been trading while insolvent for some time. A creditor agreement struck in early 1773 to write off 70 to 75 percent of the debt of Clifford’s demonstrated the depth of the problems.

Gambling for Resurrection

In the banking literature, it has been long recognized that distressed banks engage in excessive risk taking (gambling for resurrection) and moral hazard. Although not a bank, Clifford’s may also have gambled for resurrection. Clifford’s funding strategy seems to have been built on leveraging its reputation, size, and opacity, to raise unsecure funding at volumes and rates it likely could not have secured if the full extent of its risk-taking had been understood. Many contemporary observers believed that the attempt of Clifford’s and its syndicate partners to corner the market for EIC shares was a final throw of the dice in response to a long-deteriorating financial condition.

Too-Big-To-Fail

The failure of Clifford’s has remarkable parallels to the Lehman bankruptcy in 2008-9 in that the failure of a large, interconnected wholesale player turned what was mostly perceived as low-risk, money-like investments into high-risk assets virtually overnight (that is, became information sensitive). Hitherto unknown interlinkages emerged, and entire firms fell as a result. London investors, for example, lost money lent to the firm of Craven which lost on the Anglo-Dutch firm of Maurice Dreyer, which in turn, had heavily invested in one of the Clifford syndicate partners. As with Lehman, the failure of a large financial institution and the unexpected chains of risk contagion became a catalyst for concerted public sector actions to stabilize the financial system.

In Closing

Although banks retain a special role in the financial system, which dates back to the 19th century, the crisis of 1772 demonstrates that a sophisticated financial system can thrive and fail without banks. Asset cycles, gambling for resurrection, moral hazard and too-big-to-fail issues persist in a world with or without banks. As happened with the rescue of large banks during prior crises, public authorities deemed rescue operations to be the lesser of two evils when large NBFIs failed. The recent growth of non-bank financial firms may thus be viewed, not as something novel, but as the pendulum swinging back to something very old.

Stein Berre is a director in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Supervision Group.

Asani Sarkar is a financial research advisor in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Stein Berre and Asani Sarkar, “Financial Fragility without Banks,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 17, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/04/financial-fragility-without-banks/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Because narrow banking with strict anti-trust would be impossible.

For most years the agio was very stable, about 4% according Van Dillen. After 1783 it dropped slowly from 4, 3, 2, 1 to almost 0% in 1790. Source: Koers van het bankgeld tussen 1724-1790. Inv. 5059/138 Handschriften: Aantekeningen van J.G. van Dillen