Numerous studies have documented the rising dominance of large firms over the last few decades in many industrialized countries. Many research papers have focused on the potential negative effects of this increased market concentration, raising concerns about market power in both labor and product markets. In a new study, we investigate whether large firms also generate positive effects. Our research shows that large firms generate significant positive total factor productivity (TFP) spillovers to their domestic suppliers. To date, these types of spillovers have only been identified for multinational enterprises located in developing countries. Using firm-to-firm transaction data for an industrialized country, Belgium, we find that large domestic firms, as well as multinationals, generate positive TFP spillovers.

Event Study

We use the universe of firm-to-firm transaction data for Belgian firms between 2002 and 2014 to study whether a firm located in Belgium that starts a new relationship with a “superstar” firm has higher TFP after the relationship starts. (TFP reflects technological and organizational changes that boost output for a given quantity and quality of inputs.) We define a firm as being treated if it reaches a point where more than 10 percent of its sales are to a superstar firm, for three different types of superstars: large firms, multinationals, and exporters. The TFP of the treatment firms is compared to the TFP of a control group, comprising firms who never sell to a superstar firm.

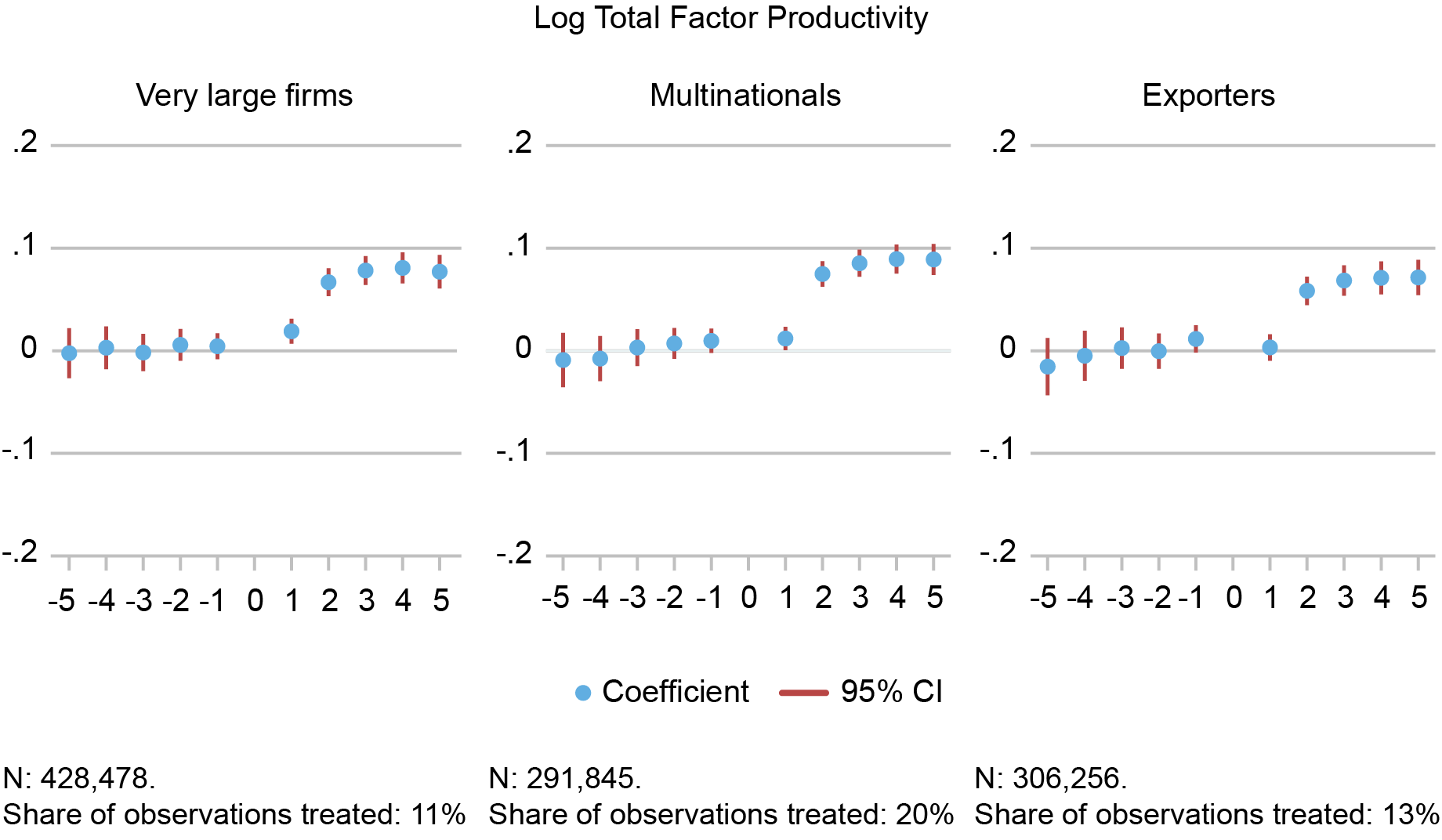

The first chart below plots the TFP of a “treated” firm for each year before and after treatment, for example, with “1” on the horizontal axis indicating the year of treatment and all dots indicating the effect relative to the year before treatment (“0”). The chart shows that by three years after the event, firms located in Belgium that started selling to a superstar firm enjoyed around 7 to 8 percent higher TFP than the control group. Interestingly, the magnitude of the spillovers is roughly the same for all three types of superstar firms. This result suggests that the spillovers emerge not from a partner firm being a multinational per se, but rather from the superstar firm being more productive and successful. These are not the same. We show that these performance effects exist even if a large firm is not a multinational or an exporter.

Forming a New Relationship with a Superstar Firm Raises Productivity

Source: Amiti et al. (2023).

Notes: These results are produced by event studies comparing productivity of firms starting a major supply relationship with a superstar firm (the treatment group) with firms who do not start such a relationship (the control group). In the left panel, the superstar is defined as a very large firm (top 0.1 percent of the sales distribution), in the center panel the firm is a multinational, and in the right panel an exporter. The y-axis is in logarithmic scale, so 0.5 = 5 percent. N is number of observations. CI is confidence interval.

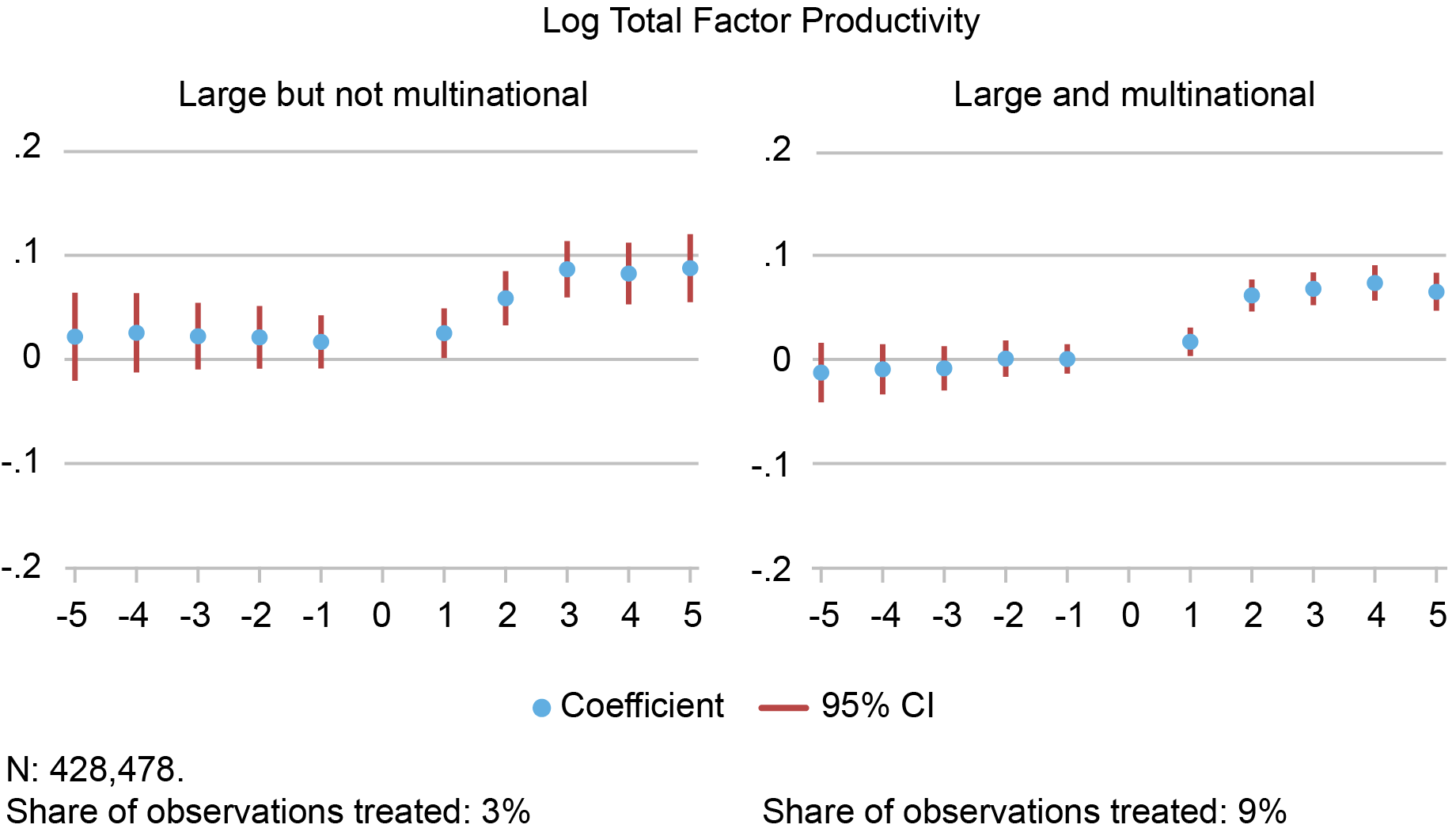

Of course, very large firms are also often multinationals. But we show that the superstar spillovers are there even when we look at starting relationships with very large firms that are not multinationals in the chart below. Further, we show that there is no effect from forming serious supply relationships with small firms suggesting that the superstar relationship is causal.

The positive growth in productivity implies that a firm should also grow in scale and, indeed, we also see sales jumping up by about 28 percent for supplier firms. This effect remains even after netting out the sales going to the superstar firm. Similarly, we see big increases in intermediate inputs, labor, and capital, as well as the number of buyers other than the superstar.

Positive Productivity Spillovers for New Suppliers, Even If the Large Firm Is Not a Multinational

Source: Amiti et al. (2023).

Notes: These are the same event studies as the first panel of the chart above, but we split the very large firms into those that are multinationals (right panel) and those that are not (left panel). The y-axis is in logarithmic scale, so 0.5 = 5 percent. CI is confidence interval.

What Are the Mechanisms behind Superstar Spillovers?

The classic reason for spillovers is the transferal of know-how. We show that superstars that have higher R&D, more managerial know-how/skills, and are more IT-intensive generate the largest spillovers. The analysis also finds that new suppliers to superstars experience higher overall profits, but the average markup falls as superstars will capture some of the relationship rents. While the supplier has lower markup on its sales to the superstar, it increases its overall profits by expanding the number of buyers it supplies to, both within and outside the superstar firm’s network.

We also show new evidence of a non-productivity-related spillover generated when a superstar firm relationship helps a supplier access a new network of potential customers. We call this a “dating agency” effect to reflect the matchmaking role of the superstar firm. This spillover benefit could be working through just reducing the search costs of suitable buyers, or via a signal effect, when dealing with the superstar firm causes other firms to update their beliefs over the quality of the supplier (and these signaling effects are particularly strong in-network). Indeed, we find particularly large positive effects on the number of buyers within the superstar’s network, consistent with a dating agency effect.

Conclusions

Governments spend large sums of money to attract and retain multinationals, partly because of their belief in the importance of these supply chain benefits. Our results highlight that being global per se is not necessary to generate spillovers. We show that large domestic firms generate TFP spillovers of the same magnitude as multinationals. Although there may be potential costs associated with the dominance of large firms in the modern economy (identified, for example, in research on market power and political influence), our work shows some advantages to allowing superstar firms to grow and form relationships with less successful firms.

Mary Amiti is the head of Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Cédric Duprez is an economist at the National Bank of Belgium.

Jozef Konings is a professor of economics and dean of the Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Business, and director of the Center for Regional Economics (VIVES) at KU Leuven.

John Van Reenen is the Ronald Coase Chair in Economics and a school professor at the London School of Economics.

How to cite this post:

Mary Amiti, Cédric Duprez, Jozef Konings, and John Van Reenen, “Do Large Firms Generate Positive Productivity Spillovers?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 12, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/10/do-large-firms-generate-positive-productivity-spillovers/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics