Despite the existing safety net, worker displacement continues to have severe consequences that motivate the consideration of new social insurance programs. Wage insurance is a novel policy that temporarily provides additional income to workers who lose their job and become re-employed at a lower wage. In this post, we draw on evidence from our recent working paper analyzing the effects of a U.S. wage insurance program on worker earnings and employment outcomes. Among workers displaced by international trade, we find that eligibility for wage insurance increased the probability of employment in the first two years following job loss and led to higher long-term earnings. The program resulted in net savings to the government because workers collected fewer benefits and paid taxes on their increased earnings. Together, these findings suggest that wage insurance could support displaced workers more effectively than traditional social insurance programs.

A Novel Social Insurance Program for Layoffs

Some jobs disappear. Industrial structure shifts due to technological change, international competition, offshoring, environmental regulations, and other secular trends. Economic downturns often lead to prolonged unemployment, particularly for workers in cyclical industries. Regardless of the source, the negative effects of displacement are severe for many workers, especially those who have acquired job-specific skills over long tenures. Research suggests a causal link between job displacement and broader societal problems, including lower educational attainment of children, political polarization, and higher rates of mortality. Although unemployment insurance temporarily cushions the impacts of job loss, and retraining can help some workers gain new skills, these policies are often insufficient to compensate workers whose livelihoods are lost. Given the likelihood of ongoing labor market disruption from emerging technologies, including AI and decarbonization, policymakers may have an interest in alternative policies.

One novel option is wage insurance, which provides additional income to displaced workers who find re-employment at a lower wage. In recent research, we studied the wage insurance provisions of the U.S. Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program, which compensates workers who lose employment because of international trade. Displaced workers in the traditional TAA program participate in mandatory job training and receive extended unemployment insurance payments. Workers aged 50 or older are additionally eligible for a wage insurance program, Reemployment Trade Adjustment Assistance, which does not require job training and instead pays a wage subsidy of up to half the difference between workers’ pre- and post-separation wages for up to two years. Because the amount of the subsidy is proportional to the earnings decline, the policy makes re-employment more attractive, particularly in lower-wage jobs, and directs larger benefit payments to workers who lose the most following displacement.

Estimating the causal effect of any voluntary social insurance program is challenging. Those receiving benefits may be self-selected on various characteristics that relate to future outcomes. For example, workers receiving wage insurance payments must experience wage declines to be eligible. Therefore, comparisons between those who receive wage insurance payments and those who don’t could reflect underlying differences in the two groups rather than the causal effect of the policy on either group of workers.

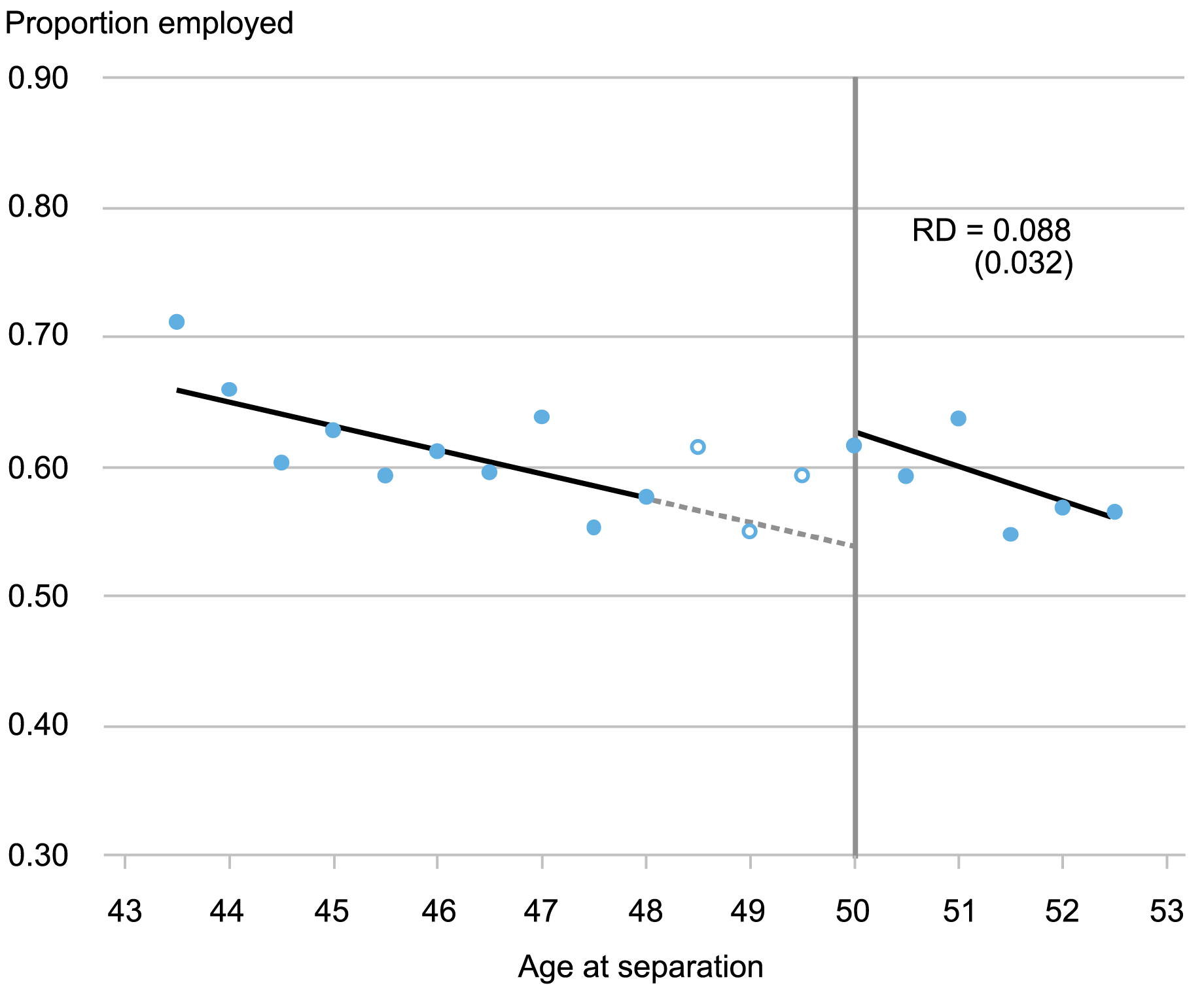

To circumvent these challenges, we leverage the requirement that workers must be age 50 or older when re-employed to be eligible for wage insurance. After the TAA petition for a given layoff event is certified by the Department of Labor, the associated workers qualify for the baseline TAA benefits of training and extended UI payments described above. Those aged 50 or older are eligible for both standard TAA benefits and wage insurance, while younger workers only qualify for standard TAA. We therefore use a regression-discontinuity (RD) design that compares employment and earnings outcomes for workers who are slightly older than age 50 when displaced to those for workers who are slightly younger. For example, the chart below shows the relationship between the proportion of displaced workers employed eight quarters following displacement and the workers’ age at separation. The visible jump at age 50 reflects the positive effect of wage insurance on workers’ employment probability.

Employment Probability Jumps for Those Eligible for Wage Insurance

Sources: U.S. Department of Labor; U.S. Census Bureau; authors’ calculations.

Notes: The chart shows a regression discontinuity plot for the quarterly employment probability eight quarters following displacement. Hollow dots represent omitted range in which recipients are only partially eligible for wage insurance–see our paper for details. RD denotes regression discontinuity estimate of 8.8 percentage point higher proportion of workers employed, with standard error from the regression in parentheses.

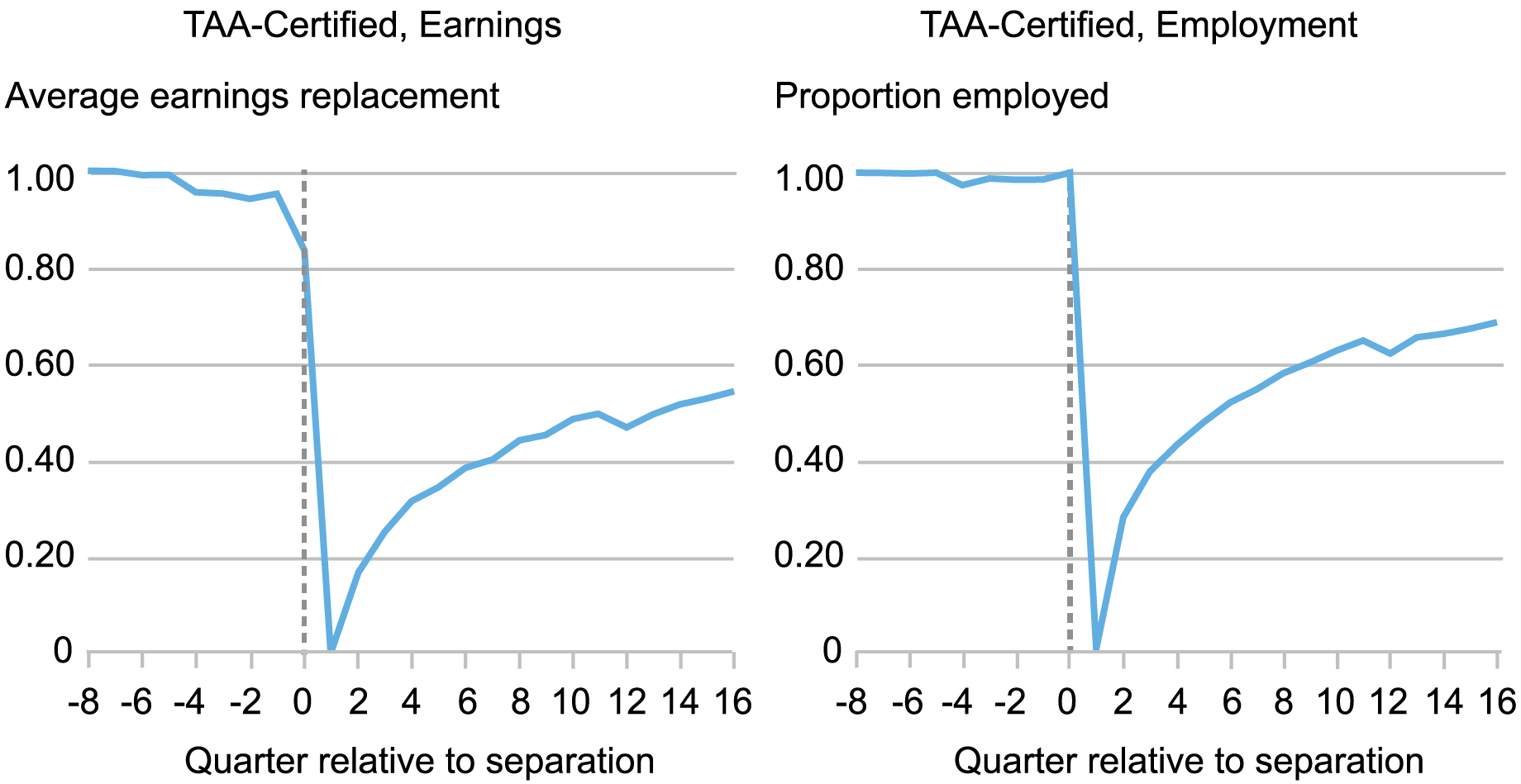

To empirically estimate the effect of wage insurance eligibility using this approach, we merge administrative data on TAA petitions with the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics data set from 2007 to 2014, which enables us to track worker earnings and employment outcomes for several years before and after job loss. Our sample covers 76,500 workers separating from approximately 1,000 TAA-petitioning firms. Compared to the average displaced worker in the United States, workers in our sample are older, have longer tenure at the displacing firm, and have lower educational attainment—all characteristics that make the consequences of job loss particularly severe. Indeed, the share of lost earnings “replaced” after job loss (left-hand panel of the chart below) and the share of workers employed (right-hand panel) remain stunted for several years beyond initial layoffs in our sample.

TAA-Eligible Workers Experience Large and Persistent Earnings and Employment Losses

Sources: U.S. Department of Labor; U.S. Census Bureau; authors’ calculations.

Notes: The left-hand panel shows quarterly earnings over mean earnings from 5 to 8 periods prior to separation, in which workers are required to be employed to be in the sample. The right-hand panel shows the proportion of displaced workers (those employed in quarter 0 and non-employed in quarter 1) who are employed in each quarter relative to separation.

The Impact of Wage Insurance on U.S. Workers

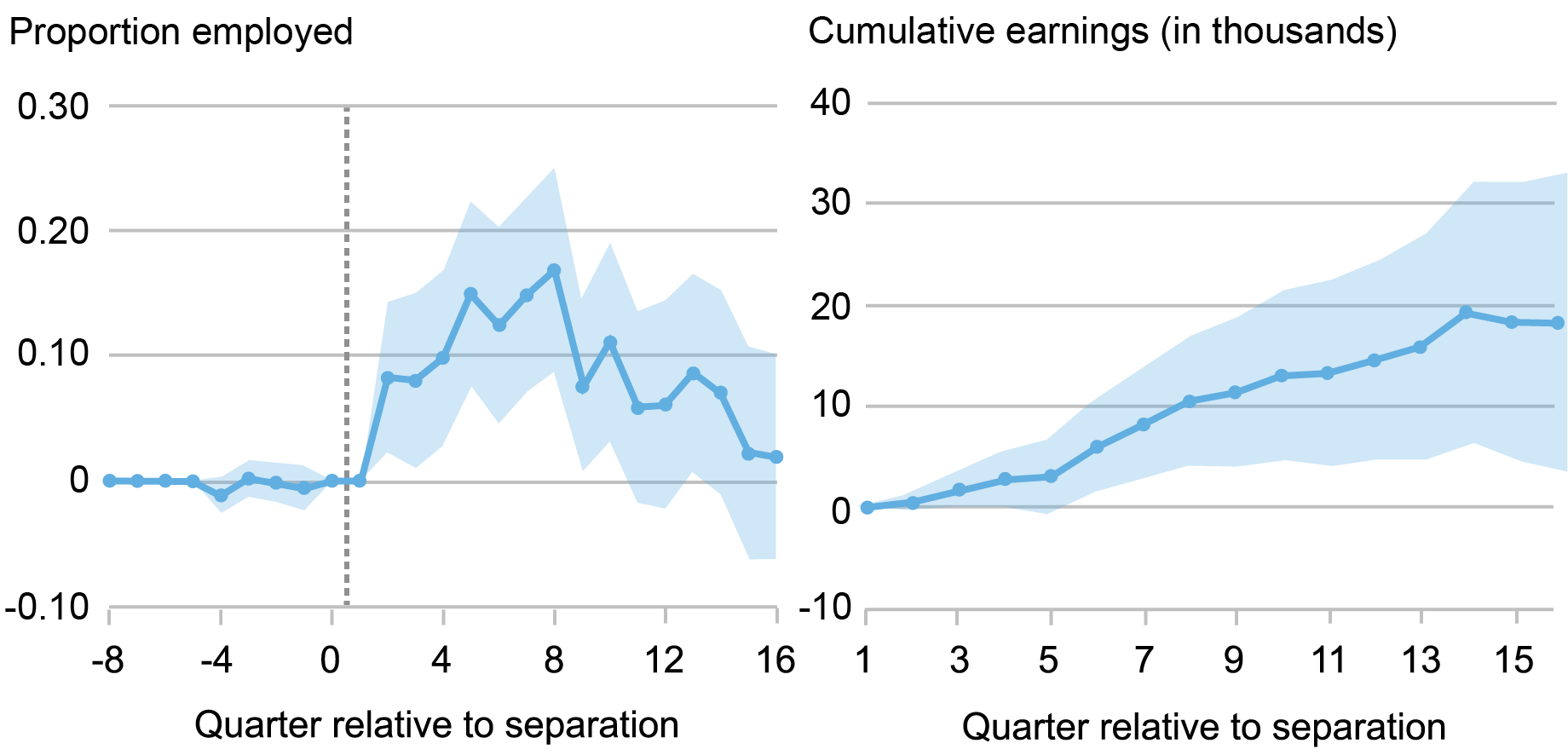

We find that wage insurance eligibility boosted workers’ employment probabilities by 8 to 17 percentage points in the two years after displacement before fading to zero after four years (left-hand panel of chart below). Program eligibility also persistently increased earnings (even omitting the value of the subsidies). On average, wage insurance eligibility increased workers’ earnings by 10 percent of their pre-displacement earnings, amounting to an increase of more than $18,000, or 26 percent, over the four years following a layoff (right-hand panel of chart below).

Effects on Employment and Cumulative Earnings over Time

Sources: U.S. Department of Labor; U.S. Census Bureau; authors’ calculations.

Note: Each dot represents a separate regression coefficient in each quarter relative to separation using our main estimation strategy, with 95 percent confidence intervals denoted in the blue shaded areas.

Overall, workers eligible for wage insurance tend to return to work more quickly following a displacing event. Shortening unemployment spells explains most of the positive effects of wage insurance eligibility on earnings, consistent with prior evidence that extended periods of unemployment harm worker outcomes. In contrast, the study found minimal effects on other employment outcomes, including industry switching rates and workers’ number of unique employers, geographic mobility, job quality (measured by firm age, firm size, and earnings growth rates), or the length of employment at the first job after displacement. The absence of declines in earnings or job quality allays concerns that wage insurance might have led to worse job matches and persistently lower wages.

Wage insurance is a very cost-effective policy in our setting. In fact, we estimate that it pays for itself; the tax receipts on increased earnings and reduced unemployment insurance payments fully offset the costs of the program. This means that the program led to net government savings while benefiting eligible workers. By contrast, most other insurance and training programs that target displaced workers are less cost-effective.

A Promising Program Warranting Further Examination

Although this particular wage insurance program is available only to workers affected by trade, the findings may have implications for a broader set of workers. Both upstream suppliers and downstream clients of firms facing trade competition are eligible for TAA, so the program’s reach extends beyond narrow industries and geographic areas and includes the service sector.

Despite these compelling findings, important questions about wage insurance remain. For example, it would be valuable to understand how wage insurance affects other important outcomes like mortality, which has been shown to increase after job loss. Also, a larger scale wage insurance program might lead employers to lower wage offers, with the knowledge that some of their applicants will receive subsidies. This response would blunt the favorable effects for workers that we find in a smaller-scale program. Nonetheless, the existing program was cost-effective, and our results suggest that wage insurance is a promising policy to support economically vulnerable workers.

Ben Hyman is a research economist in Urban and Regional Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Brian Kovak is a professor economics and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University.

Adam Leive is an assistant professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley.

How to cite this post:

Ben Hyman, Brian Kovak, and Adam Leive , “Wage Insurance: A Potential Policy for Displaced Workers,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, July 17, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/07/wage-insurance-a-potential-policy-for-displaced-workers/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics