Why do banks fail? In a new working paper, we study more than 5,000 bank failures in the U.S. from 1865 to the present to understand whether failures are primarily caused by bank runs or by deteriorating solvency. In this first of three posts, we document that failing banks are characterized by rising asset losses, deteriorating solvency, and an increasing reliance on expensive noncore funding. Further, we find that problems in failing banks are often the consequence of rapid asset growth in the preceding decade.

U.S. Bank Failures in History

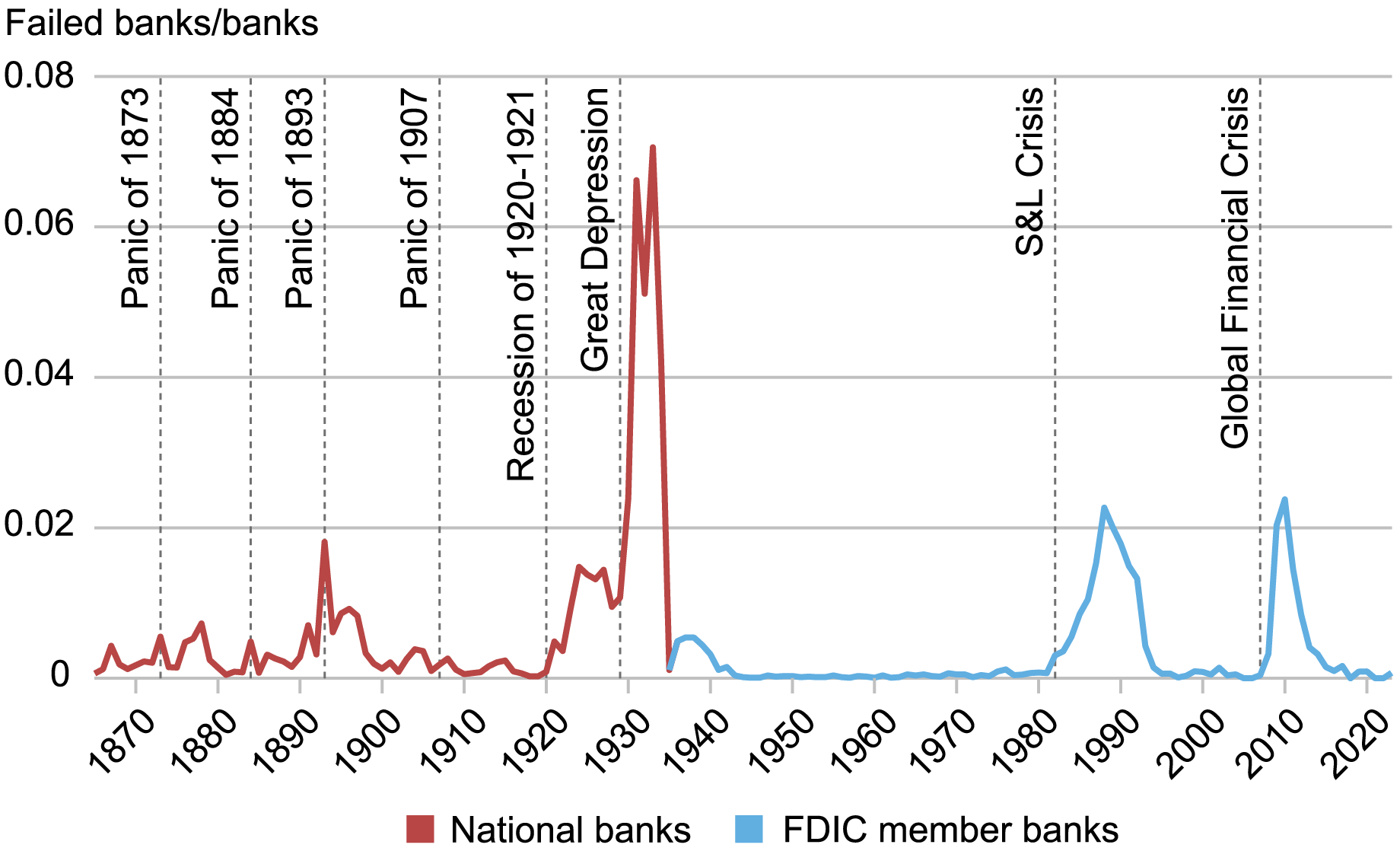

Bank failures have been a recurrent feature of the U.S. banking system over the past 160 years. The chart below plots the rate of bank failures since 1865. Spikes in bank failures have characterized the major financial crises in U.S. history, from the Panic of 1893 to the Great Depression to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

Rate of Bank Failures in the U.S. from 1865 to 2023

Sources: Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Annual Report to Congress; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). See Correia, Luck, and Verner (2024) for details.

Notes: The chart plots the ratio of bank failures to the total number of banks. The red line plots the rate of failing national banks, defined as national banks placed into receivership, as reported in the OCC’s Annual Report to Congress (various years). The blue line plots the rate of banks classified as failed by the FDIC as reported in the FDIC list of failing banks. We restrict our sample of FDIC member banks to national member banks, state member banks, and state nonmember banks and exclude savings associations, savings banks, and savings and loans. Vertical lines indicate selected major banking crises and economic downturns.

There are two primary reasons why banks fail. First, bank failures can result from bank runs, in which depositors withdraw from banks that would have survived if the run had not occurred. While bank runs can in principle bring down otherwise healthy banks or banking systems, they can be especially problematic for troubled banks that, although struggling, could be viable in the absence of a run. Second, bank failures can be caused by poor fundamentals, such as realized credit risk, interest rate risk, or fraud, that trigger insolvency irrespective of whether depositors run.

Understanding what commonly causes bank failures, in turn, has important policy implications. If bank failures are primarily due to bank runs, policy priorities should naturally gravitate toward preventing runs with tools such as emergency liquidity facilities. If, in contrast, bank failures are more commonly related to realized losses, deteriorating solvency, and unviable business models, more attention should be paid to ensuring adequate capitalization of banks, both before and during crises.

A Novel Data Source

To understand the causes of bank failures, we construct an exciting new database with balance sheet information for most banks in the U.S. since the Civil War. Our data consist of a historical sample that covers all national banks from 1865 to 1941 and a modern sample that covers all commercial banks from 1959 to 2023. Thus, our data go far beyond the time horizon typically considered in academic work, which has—due to data availability—typically focused on the period from 1976 onward.

Our long-run historical perspective for understanding bank failures is valuable for two reasons. First, it allows us to study thousands of bank failures. Altogether, our data consist of balance sheets for around 37,000 distinct banks, of which more than 5,000 fail. Second, it allows us to study bank failures before the advent of government interventions aimed at preventing bank runs, such as deposit insurance and the lender of last resort authority of the Federal Reserve System.

Three Facts About Failing Banks

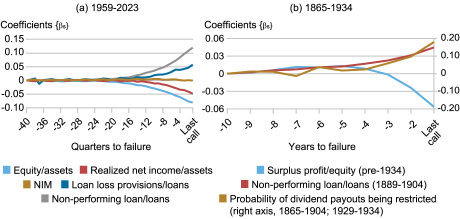

Fact 1: Failing banks see rising losses and deteriorating solvency before failure.

The left panel of the chart below plots the dynamics of capitalization, net income, and nonperforming loans (NPLs) in failing banks in the decade before failure for banks that failed between 1959 and 2023. Specifically, the plots show regression coefficients indicating how these variables evolved in the ten years before a bank failed relative to their values exactly ten years before failure. We find that in the years before failure, there is a 10 percentage point rise in NPLs. This increase translates into rising loan loss provisions, which result in a decline in realized net income. The fall in net income depresses the return on assets by 5 percentage points in the year before failure. As a result, the equity-to-assets ratio declines considerably in the run-up to failure, falling by 10 percentage points. Net interest margins, in contrast, are stable.

Rising Asset Losses and Deteriorating Solvency in Failing Banks

Sources: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (“Call Reports”); Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Annual Report to Congress; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). See Correia, Luck, and Verner (2024) for details.

Notes: The chart plots the evolution of the ratio indicated in the chart legend in the ten years before failure. Additional details on the underlying regression model used to obtain the sequence of coefficients can be found in Correia, Luck, and Verner (2024). In the left panel, the net interest margin (NIM) is defined as the difference of total interest income net of interest expenses normalized by total assets. In the right panel, surplus profit to equity is the sum of the surplus fund and undivided profits relative to total equity capital (paid-in capital, undivided profits, and surplus fund). Nonperforming loans is proxied by the line item “other real estate owned (OREO)” and is available for the 1889-1904 subsample. The probability of dividend payouts being restricted is based on the share of banks with undivided profits of total equity falling short of 1 percent. This measure captures restrictions on dividend payouts due to low capitalization and is available for 1865-1904 and again after 1929.

The right panel of the chart plots similar measures for the bank failures that occurred from 1865 to 1934. Despite differences in accounting standards, banks that failed in the historical sample display signs of trouble similar to those that failed in the modern sample. In particular, these banks also see a gradual rise in the share of NPLs and a gradual deterioration in surplus profits (akin to retained earnings) relative to total equity, indicating declining profitability and capitalization. In the paper, we further show that, once these banks enter failure, the loss rates on their assets amount to 49 percent on average, indicating that failing banks typically suffered large losses on their loans and other assets in the historical sample.

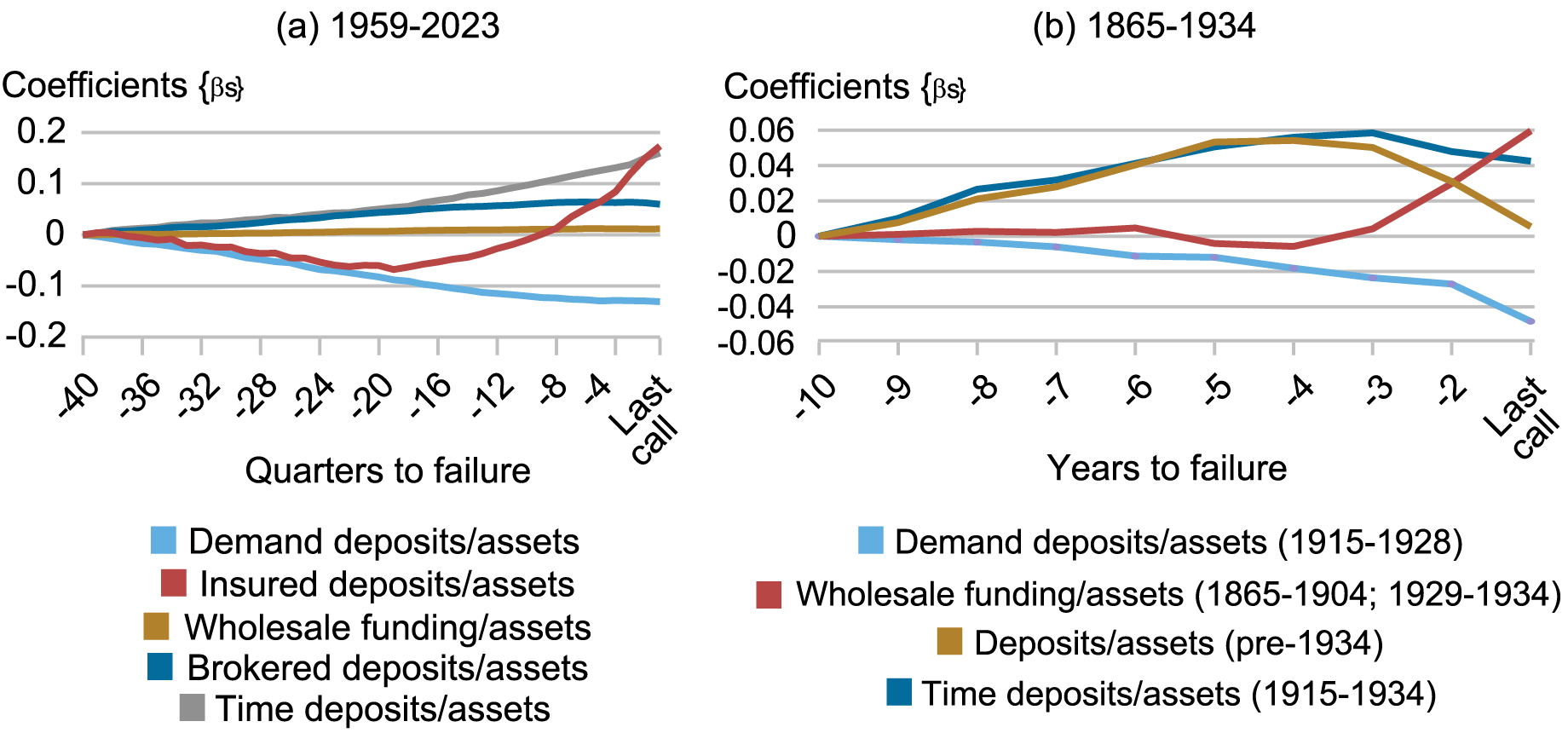

Fact 2: Failing banks rely increasingly on noncore funding.

How does bank funding evolve as a bank approaches failure? The left panel of the chart below presents the evolution of various funding ratios for banks that failed between 1959 and 2023. Failing banks increasingly rely on what we refer to as noncore funding: expensive types of deposit funding or non-deposit wholesale funding. In particular, the largest increase is accounted for by time deposits, followed by brokered deposits. Failing banks also increasingly rely on non-deposit wholesale funding. These types of funding are typically more expensive than demand deposits, as the corresponding interest rates are more sensitive to movements in the risk-free rate in the economy. These types of funding also tend to be “flighty” and more sensitive to a bank’s risk of default. At the same time, failing banks start to see an inflow of insured deposits mirrored by an outflow of uninsured deposits, in line with depositors seeking to deposit amounts under the deposit insurance limit in failing banks.

Increasing Reliance on Expensive Noncore Funding in Failing Banks

Sources: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (“Call Reports”); Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Annual Report to Congress; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). See Correia, Luck, and Verner (2024) for details.

Notes: The chart plots the dynamics of the funding ratios indicated in the chart legend in the ten years before bank failure. Additional details on the underlying regression model used to obtain the sequence of coefficients can be found in Correia, Luck, and Verner (2024). In the left panel, wholesale funding is the amount reported in the call report line item “other borrowed money,” which pools various sources of bank wholesale funding, such as advances from Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs), other types of wholesale borrowings in the private market, and credit extended by the Federal Reserve. In the right panel, wholesale funding is defined as the sum of “bills payable” and “rediscounts.” Time and demand deposits are reported separately for the 1915-1928 subsample.

The right panel of the chart shows the evolution of funding ratios in failing banks for banks that failed during 1865-1934. As in the modern sample, these banks increasingly rely on time deposits. Before deposit insurance, deposit funding as a share of total assets starts to decline in the two years before failure, similar to the decline in uninsured deposits for failures in the modern sample. The outflowing deposits are replaced nearly one-for-one by more expensive non-deposit wholesale funding, likely reducing bank profitability. Thus, in both the historical and modern periods, failing banks increasingly rely on expensive and more risk-sensitive forms of funding.

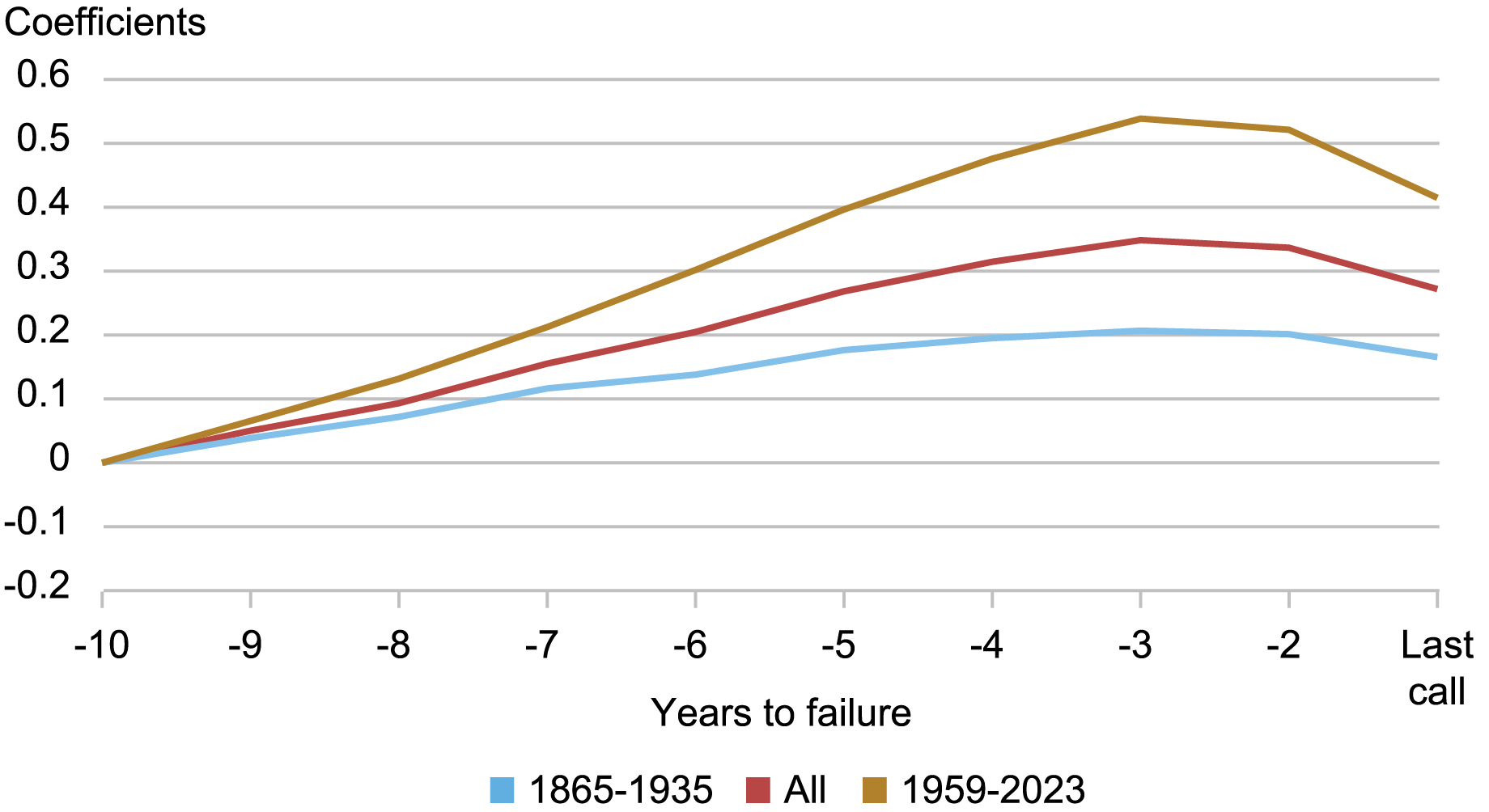

Fact 3: Failing banks follow a boom-bust pattern. They grow rapidly, both in absolute terms and relative to their peers, up to three years before they fail, and then they contract.

Why do banks experience gradually rising losses that eventually lead to failure? The chart below reveals that total assets in failing banks follow a boom-and-bust pattern in the decade before failure. In the full sample, assets expand by over 30 percent in real terms from ten years to three years before failure and then contract over the last two years before failure. This asset growth is typically driven by rapid growth in real estate lending. The chart also shows the dynamics of assets in failing banks separately for the pre-1935 sample and the modern sample. The boom-and-bust pattern is present in both samples. However, it is significantly more pronounced in the modern period.

Asset Boom and Bust in Failing Banks

Sources: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (“Call Reports”); Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Annual Report to Congress; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). See Correia, Luck, and Verner (2024) for details.

Notes: The chart plots the dynamics of total assets (deflated by the CPI). The sub-samples indicated in the chart legend are selected based on the years in which a bank failed. Additional details on the underlying regression model used to obtain the sequence of coefficients can be found in the paper.

Wrapping Up

This post presents three facts about failing banks. The typical failing bank goes through a boom before entering a bust. As failing banks boom, they increasingly finance themselves with expensive forms of noncore funding. As failure approaches, these banks experience rising losses and deteriorating solvency. All three patterns point to the central role of deteriorating fundamentals and rising insolvency risk for bank failures. In the next post, we ask whether these patterns allow us to predict bank failures and we discuss implications for the causes of bank failures.

Sergio Correia is a principal economist in the Financial Stability Division at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Stephan Luck is a financial research advisor in Banking Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Emil Verner is an associate professor of finance at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

How to cite this post:

Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner, “Why Do Banks Fail? Three Facts About Failing Banks,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, November 21, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/11/why-do-banks-fail-three-facts-about-failing-banks/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

After working for a successful bank for 20 years, I’m pretty sure bank failures mostly occur because of bad management. The bank I worked for bought several failed banks during my tenure and more since. Good management includes good supervision by senior officers.

And yet… basically no bank failures between 1940 and 1980. Glass-Steagall, anyone?

It would seem that we know perfectly well how to avoid bank failures. The real question is this: why do we allow bank failures? And surely the answer is that wealthy financial interests can make a lot of money off of either the bank failures themselves, or perhaps the conditions of the run up to the bank failures.

For subsequent research considerations. How did boards of directors contribute to, and bear any loss from, those failures? Were there any criminal prosecutions of management or others from the failures? What tools could help regulators and customers understand and deal with risk profiles of financial institutions?