The term “exorbitant privilege” emerged in the 1960s to describe the advantages derived by the U.S. economy from the dollar’s status as the de facto global reserve currency. In this post, we examine the exorbitant privilege that accrued to the Netherlands in the eighteenth century, when the Dutch guilder enjoyed global reserve currency status. We show how the private actions of financial institutions created and maintained this privilege, even in the absence of a central bank. While privilege benefited the Dutch financial system in many ways, it also laid the seeds of later financial crisis.

Origins of the Netherlands’ Exorbitant Privilege

A country’s exorbitant privilege allows it to borrow and lend using its own currency on more favorable terms than other countries using their local currencies. As the U.S. has been the sole beneficiary of exorbitant privilege since World War II, researchers look to history to understand privilege’s determinants. Prior studies have examined the exorbitant privilege enjoyed by the United Kingdom in the nineteenth century, when the British pound was the global reserve currency. We focus on the experience of the Netherlands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as the Netherlands had a different financial system from the UK at the time and from the U.S. today. In particular, as the Netherlands did not have a central bank and its financial intermediaries were nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs), its exorbitant privilege grew out of the private actions of these NBFIs, as we show below.

The role of the Dutch guilder as the global reserve currency allowed the Netherlands to have the lowest prevailing rate of interest in Europe, as foreign investors were more willing to exchange their surpluses for financial assets in the Netherlands. One consequence was that foreign investors left large deposits with the leading merchant banks of Amsterdam. Since these deposits paid no interest, they provided these firms with a source of low-cost funding.

Hope & Co.: A Case Study of Exorbitant Privilege

To provide a more granular view of how the Dutch system operated, we analyze the ledgers of Hope & Co., the largest private financial firm in the Netherlands in the early 1770s, when Amsterdam was likely still the largest financial center in Europe. Hope was a broker-dealer, trading in commodities, securities, and money markets; it also issued securities and was one of the leading cross-border payments providers. Between 1770 and 1775, more than 1,200 active international clients maintained accounts with Hope, most of which contained callable, non-interest-bearing balances, like wholesale deposits in modern times.

About 20 percent of Hope’s clients held balances but transacted infrequently. Some of these clients, particularly those far from Amsterdam such as in Russia or the West Indies, may have been using their accounts as a safe, offshore store of value. These accounts also served as a means of payment, since the Bank of Amsterdam (AWB), the primary entity for clearing money market transactions, restricted foreign firms from holding accounts with it.

The remaining 80 percent of Hope’s clients tended to keep large balances (see chart below)—but only temporarily. In some cases, clients placed funds in anticipation of large outlays (such as purchases of foreign goods when the Dutch East India shipping fleet returned to Amsterdam). In other cases, they held funds in joint venture accounts, expecting to use them for business ventures. Finally, clients held monies for future interest payments on bonds as well as in anticipation of speculation or other opportunities.

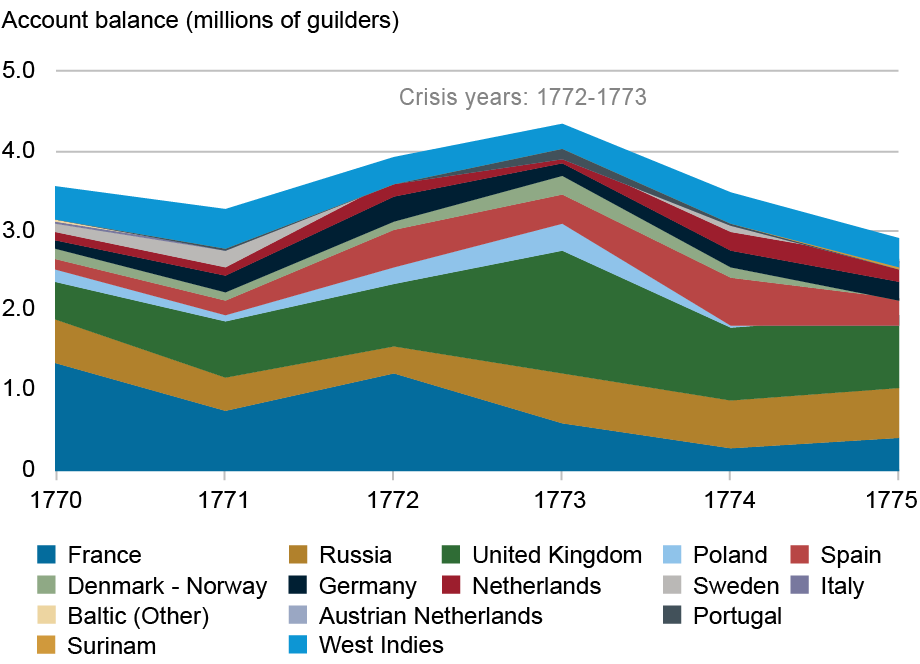

Foreign Depositors Held Large Balances with Hope & Co.

Notes: The chart shows balances in accounts held by foreign depositors at Hope & Co. by region of origin. The sample period is 1770-75.

The temporary nature of deposits implies that, at the individual client level, deposit balances were volatile over time (see chart below), with a coefficient of variation (in other words, the standard deviation of an account balance divided by the average balance) of 73 percent on average. However, if clients did not withdraw deposits at the same time, Hope’s large base of international depositors afforded a great deal of diversification, so that for the entire portfolio, the coefficient of variation was just 30 percent.

Individual Account Balances Were Highly Volatile

Percent

Notes: The chart shows the coefficient of variation of balances in accounts held by foreign depositors at Hope & Co. by region of origin, averaged over all accounts in the region. One region with a negative average balance is excluded. The sample period is 1770-75.

In addition to providing a liquidity reserve, Hope’s cross-border deposits formed a stable base of zero-interest funding for its own activities. Indeed, the Hopes were able to fund about two-thirds of the firm’s liabilities interest free. Given that the Hopes expected to achieve a 3-4 percent return on passive investment in a typical year, the deposit balances may have generated 15-25 percent of the firm’s immense annual profits. Hope & Co. seems to have kept about half of this investment in working capital for its core businesses and the other half on deposit with AWB. It was the largest transactor with the AWB, using its AWB deposits to regularly purchase short-term bills on the money market, lend money against securities or commodities, and speculate in the market on its own account.

Benefits for the Dutch Economy

Abundant foreign funds helped ensure that the Dutch Republic had the lowest interest rate in Europe, which helped the country to offset declining balances of merchandise trade via its large exports of financial services such as payments, credit, insurance, and brokerage. It also had the most liquid money markets in Europe, since firms like Hope could accept or discount bills profitably, even when margins were very thin.

In addition, Amsterdam became a provider of global safe assets. Political or financial turmoil in neighboring countries tended to draw in additional deposits for safekeeping. This allowed Hope & Co. and other large merchants in Amsterdam to function as private “lenders of last resort” and stabilize the Dutch economy in periods of crisis. For example, Hope & Co. was able to backstop the Amsterdam money markets during the worst months of the major financial crisis of 1772‑73. It did so by buying at a discount a large volume of riskier bills of exchange coming to the market, growing its share in discounting riskier bills from 10 percent before the crisis to 25 percent at the height of the crisis.

In turn, the stabilizing effects of interventions by large merchant banks incentivized the flow of new cross-border deposits during crises from firms seeking a safe place to store their money. Indeed, deposits at Hope & Co. surged in 1772-73 (see first chart above). This phenomenon is similar to the flow of deposits into the modern U.S. banking system during crisis periods.

Final Thoughts

The exorbitant privilege enjoyed by the Dutch in the eighteenth century arose from the role of the guilder as the global reserve currency and the actions of NBFIs that provided safe assets to foreigners and large domestic firms. In turn, the NBFIs profited from this arrangement by having access to zero-interest-rate funding and helped to stabilize the Dutch financial system during crises.

Exorbitant privilege, however, can be a double-edged sword. The availability of cheap money resulted in risky behavior by large, highly leveraged wholesale players and a financial crisis in 1772, leading to boom-and-bust cycles in such assets as plantation mortgages, foreign sovereign lending, and leveraged bets on the performance of equities. Once the guilder lost its reserve currency status at the turn of the nineteenth century due to war and revolution, the Netherlands was no longer able to finance its massive debt at low rates, and its perch at the top of international public finance collapsed.

Stein Berre is a principal examiner in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Supervision Group.

Asani Sarkar is a financial research advisor in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Stein Berre and Asani Sarkar, “Dutch Treat: The Netherlands’ Exorbitant Privilege in the Eighteenth Century,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 7, 2025, https://doi.org/10.59576/lse.20251007

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics