M. Henry Linder, Richard Peach, and Robert W. Rich

Following a significant slowing during the recent recession, growth in various

labor compensation measures has stabilized during the past two to three years. This

stabilization is puzzling because it’s widely held that a significant amount of

slack remains in the economy. Accordingly, this large amount of slack should

result in a further slowing in compensation (wage) growth. In this post, we

show that there’s a very mild trade-off between compensation growth and

resource slack, even though slack is sizable. Consequently, the observation that

there’s slow but steady growth in labor compensation measures is consistent with

a large amount of slack in the current economic environment.

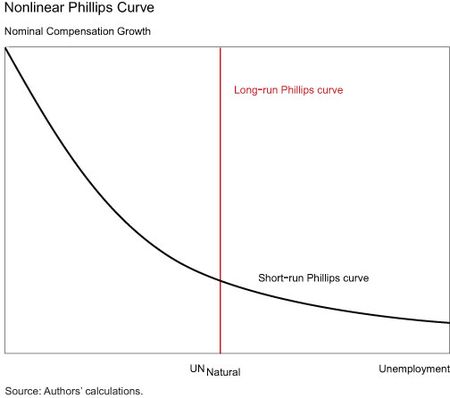

Our analysis is based on the

estimation of a nonlinear wage-inflation Phillips curve that draws upon the modeling

approach outlined in a Boston Fed paper by

Fuhrer, Olivei, and Tootell. The key feature of the nonlinear Phillips curve is

that the impact of a change in slack depends on the level of slack. These features

are illustrated in the chart below, where the slope of the Phillips curve

becomes steeper as the unemployment rate moves further below the natural rate of

unemployment (higher resource utilization), while the slope becomes flatter as

the unemployment rate moves further above it (lower resource utilization).

Why might the Phillips curve flatten

out as the unemployment rate rises further above the natural rate of

unemployment? As a reminder, what matters for labor market decisions is the

real wage rate—the nominal wage adjusted for the price level (or cost of

living). One explanation for the flattening of the Phillips curve is downward

real wage rigidity—that is, a more sluggish response of real wages when the

unemployment rate is high (see the Boston Fed paper by

Holden and Wulfsberg for a more detailed discussion of theories of real wage

resistance during an economic downturn). In a situation of high unemployment,

wage growth becomes relatively stable around the recent level of underlying

inflation, so that real wages don’t fall sufficiently to clear the labor

market.

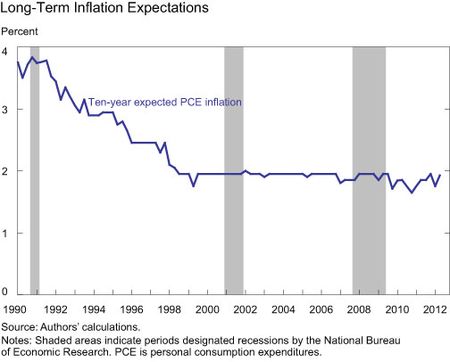

Our Phillips curve model relates

four-quarter growth in nominal compensation per hour (for the nonfarm business

sector) to economic slack, controlling for movements in trend productivity

growth and expected inflation. Our measure of slack is the Congressional Budget

Office (CBO) estimate of the unemployment gap—the percentage point deviation

between the actual unemployment rate and the CBO estimate of the natural rate

of unemployment. For trend productivity growth, we use an average of the

(annualized) quarterly growth rate of productivity. For expected inflation, we construct

a ten-year personal consumption expenditure (PCE) survey measure by adjusting

the Survey of Professional Forecasters’ ten-year expected CPI inflation series

to account for the average differential between CPI and PCE inflation. As the chart

below shows, expected inflation has been extremely stable during the post-1997

period. To provide additional observations for estimation and to conduct the

analysis in a low-inflation environment with well-anchored expectations, we use

data that cover the period from 1997 through the present.

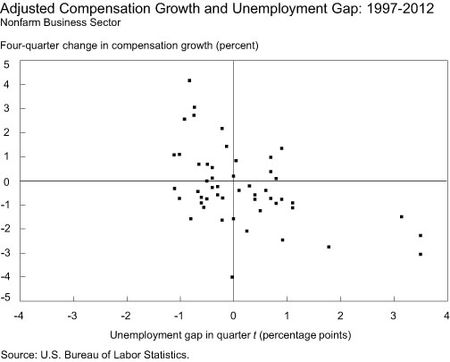

Our model relates economic slack to

an adjusted compensation measure, where we subtract the values of trend

productivity growth and expected inflation from the compensation growth series.

This adjustment imposes the standard restriction that increases in the real

wage rate equal increases in labor productivity in the long run. The chart below

provides a scatter plot of the adjusted compensation growth series and the unemployment

gap. Negative (positive) values of the unemployment gap represent conditions in

which unemployment is below (above) the natural rate of unemployment.

An examination of the scatter plot shows

that the general shape of the data points bears a close resemblance to the chart

of the nonlinear Phillips curve, and estimation of the model provides evidence

of a statistically significant nonlinear relationship between (adjusted)

compensation growth and slack. To better illustrate the nature of the estimated

nonlinearity, we consider a comparison based on the same percentage point

change in the unemployment gap. If the gap were to move from -1 percentage

point to -3 percentage points, then the four-quarter growth rate of

compensation would increase by 2.2 percentage points. If the unemployment gap were

to move from 3 percentage points (the current CBO estimate) to 1 percentage

point, then the rate would increase only by 1 percentage point.

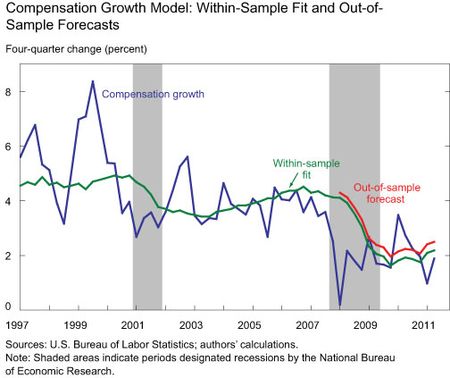

We also consider two additional

criteria to evaluate the nonlinear Phillips curve model—within-sample fit and

out-of-sample forecast performance. The within-sample fit is based on

estimation of the model using data from the full sample to compare the

predicted and actual values of growth in compensation per hour. The

out-of-sample forecast performance is based on estimation of the model only using

data through 2007:Q4 on the unemployment gap, trend productivity growth, and

expected inflation. With the resulting estimated model, we input the actual

values of the unemployment gap, trend productivity growth, and expected

inflation during the post-2007:Q4 period to generate forecasts of compensation

growth. The first forecast corresponds to compensation growth from 2008:Q1 to 2009:Q1.

The next chart plots the

four-quarter change in compensation growth, the within-sample predictions, and

the post-2007:Q4 out-of-sample forecasts. While the within-sample predictions fail

to track some short-run movements in compensation growth, they do capture the

general movements in the series. Moreover, both the within-sample predictions

and out-of-sample forecasts capture the magnitude of the decline in

compensation growth since 2008 as well as its subsequent stability.

Our analysis suggests that a

nonlinear wage-inflation Phillips curve fits the data well during the post-1997

episode and complements the results of Fuhrer, Olivei, and Tootell, who find

evidence of a nonlinear relationship between price inflation and activity gap

measures. An important conclusion from our analysis is that recent stability in

the growth rate of labor compensation measures may not be informative about the

extent of slack or its change. That is, stability in labor compensation

measures doesn’t imply that the output gap has closed, while changes in the

output gap may only have a modest impact on compensation growth.

In an inflation environment where

actual and expected price changes are low, someone might interpret the earlier

scatter plot as reflective of downward nominal wage rigidity—the idea that

workers and firms have incentives to avoid reductions in nominal wages. However,

the nonlinearity between wage growth and slack appears to be evident in other

episodes in which large fluctuations in real activity were accompanied by high

inflation and high compensation growth (this point is also discussed by Fuhrer,

Olivei, and Tootell). Thus, the mild trade-off between compensation/wage growth

and resource slack when slack is sizable isn’t unique to recent experience. Moreover,

the source of the nonlinearity must stem from downward real wage rigidity, as downward

nominal wage rigidity can generate this feature only in a low-inflation

environment.

We recognize that our analysis comes

with important caveats, which include the use of a model based on a simple,

parsimonious specification as well as the study of a single, short sample

period. Nevertheless, if the nonlinear relationship between slack and

wage/price inflation is an important feature of the data, then it will be

critical for policymakers to identify other indicators that may be more

responsive to slack and provide a quick and more reliable read on its

movements.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

M.

Henry Linder is a research associate in the Research and Statistics Group of

the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Richard

Peach is a senior vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the

Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Robert

W. Rich is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the

Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics