Cybercrime is one of the most pressing concerns for firms. Hackers perpetrate frequent but isolated ransomware attacks mostly for financial gains, while state-actors use more sophisticated techniques to obtain strategic information such as intellectual property and, in more extreme cases, to disrupt the operations of critical organizations. Thus, they can damage firms’ productive capacity, thereby potentially affecting their customers and suppliers. In this post, which is based on a related Staff Report, we study a particularly severe cyberattack that inadvertently spread beyond its original target and disrupted the operations of several firms around the world. More recent examples of disruptive cyberattacks include the ransomware attacks on Colonial Pipeline, the largest pipeline system for refined oil products in the United States, and JBS, a global beef processing company. In both cases, operations halted for several days, causing protracted supply chain bottlenecks.

The Worst Cyberattack Ever

We examine the impact of the most damaging cyberattack in history, which caused an estimated $10 billion in damages. Named NotPetya, it was released on June 27, 2017 and targeted Ukrainian organizations in an effort by Russian military intelligence to cripple critical Ukrainian infrastructure. Even though NotPetya looked at first like a ransomware attack, its true intent was not the financial gains from ransom payments. Instead, NotPetya was designed to encrypt and paralyze the computer networks of Ukrainian banks, firms, and government.

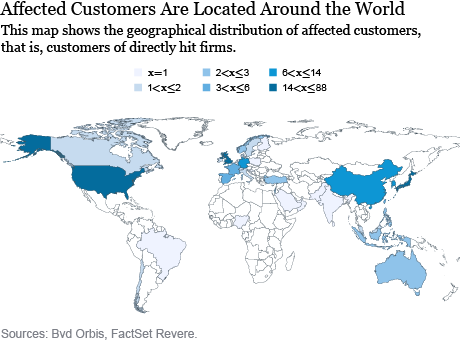

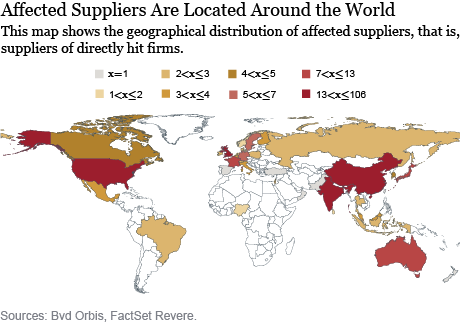

The initial vector of infection was a software that the Ukrainian government required all vendors in the country to use for tax reporting purposes. When this software was hacked and the malware released, it spread across different entities, including a few large global firms through their Ukrainian subsidiaries. For instance, the shipping company Maersk had its operations grind to a halt, creating chaos at ports around the globe. A FedEx subsidiary was also affected, becoming unable to take and process orders. Manufacturing, research, and sales were halted at the pharmaceutical giant Merck, making it unable to supply vaccines to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Several other large companies (e.g., Mondelez, Reckitt Benckiser, Nuance, Beiersdorf) had their servers taken down and could not carry out essential activities. The maps below show the geographical locations of affected customers and suppliers of the firms directly hit by the cyberattack. The maps suggest the possibility that the cyberattack could affect multiple firms through supply chain relationships.

Propagation of the Cyberattack

To study the propagation of the cyberattack through firms’ supply chains, we compare the change in profitability of affected customers before and after the cyberattack to the change in profitability of similar firms that do not have supply linkages to the directly hit firms. The difference between these two changes can be then attributed to the supply chain disruptions caused by the cyberattack.

We find that the NotPetya cyberattack was propagated downstream to customers but not upstream to suppliers. Relative to otherwise similar firms, affected customers display a drop in profitability of 1.3 percentage points after the cyberattack. Interestingly, supply chain vulnerabilities play a role in determining the magnitude of the effect. This can happen in two ways. As firms need several intermediate inputs and services for their production, they become more vulnerable to sudden interruptions if they cannot easily replace the supplier that is hit by a shock. Indeed, affected customers that rely on fewer alternative suppliers in the same industry of the directly hit supplier display larger drops in profitability. In addition, customers of directly hit firms that produce more R&D-intensive products are more affected since these R&D inputs are harder to replace from substitute suppliers. We find that these customers also incur larger drops in revenues and profitability.

Liquidity Risk Management

To cope with the effect of the shock, affected customers use both internal and external liquidity. Specifically, they reduce their liquidity ratio—a measure of the internal liquidity of the firm, and defined as current assets minus inventories divided by current liabilities. In addition, affected customers increase their use of external funding, mostly by drawing down pre-existing credit lines with banks. However, this comes at a cost since banks subsequently consider the affected customers to be riskier and therefore charge them higher rates. Thanks to their access to internal and external financing, affected customers navigate the shock without cutting their investment or employment.

Endogenous Network Response

The NotPetya cyberattack exposed the possibility of protracted business interruptions and served as a wake-up call for affected customers. Accordingly, we find that affected customers are more likely to form new relations with alternative suppliers after the shock—that is, other suppliers in the same industry where the directly hit firms are located. Over time, they are also more likely to terminate the supply relation with the directly hit supplier.

Takeaways

As cybercrime becomes a greater source of risk for corporations and governments, it is of utmost importance to study the potential effects of severe cyberattacks. In this post, we show that certain malicious cyberattacks designed to paralyze IT infrastructures can have devastating effects not only on the directly hit firms, but also on other firms through supply chain linkages. In doing so, we document the advantages of well diversified supply chains with several alternative suppliers. We also point out the role of bank credit in enabling affected customers to absorb the shock. Importantly, in this specific event, banks were not hit by the NotPetya cyberattack and could provide credit to firms. A potentially more devastating scenario could have occurred had banks been hit as well, potentially making them unwilling or unable to provide additional credit.

Matteo Crosignani is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Matteo Crosignani is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marco Macchiavelli is a senior economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Marco Macchiavelli is a senior economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

André F. Silva is an economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

André F. Silva is an economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

How to cite this post:

Matteo Crosignani, Marco Macchiavelli, and André F. Silva, “Cyberattacks and Supply Chain Disruptions,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, June 22, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/06/cyberattacks-and-supply-chain-disruptions.html.

Related Reading

Pirates without Borders: The Propagation of Cyberattacks through Firms’ Supply Chains (Staff Report)

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics