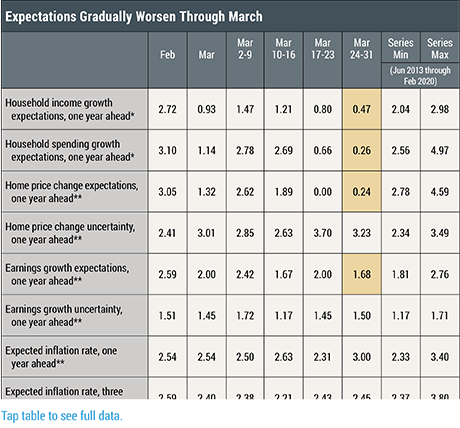

The New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data released results today from its March 2020 Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE), which provides information on consumers’ economic expectations and behavior. In particular, the survey covers respondents’ views on how income, spending, inflation, credit access, and housing and labor market conditions will evolve over time. The March survey, which was fielded between March 2 and 31, records a substantial deterioration in financial and economic expectations, including sharp declines in household income and spending growth expectations. As shown in the first two columns of the table below, the median expected year-ahead growth in income and spending declined from 2.7 percent and 3.1 percent in February to 2.1 percent and 2.3 percent in March, respectively. Similarly, expectations about home price growth plunged from 3.1 percent in February to 1.3 percent in March. The March reading for one-year home price growth expectations came in about 1.4 percentage points below the previous low for the series, which stretches back to June 2013.

With respect to labor market expectations, median earnings growth expectations for the next twelve months fell from 2.6 percent in February to 2.0 percent in March. Respondents also significantly revised up the average probability that the U.S. unemployment rate will be higher a year from now, increasing from 34.2 percent in February to 50.9 percent in March. The average perceived probability of losing a job over the next twelve months increased from 13.8 percent to 18.5 percent, while the average perceived probability of finding a new job over the next three months, in the event of a job loss today, declined from 58.7 percent in February to 53.0 percent in March.

The March SCE results also point to deteriorations in respondents’ expected future financial situation, with 27.8 percent expecting to be worse off (and 31.2 percent expecting to be better off) in March, compared to 10.5 percent (42.9 percent) in February. Similarly, we find greater concern about future access to credit and an increase in the average likelihood of missing a debt payment over the next three months. Finally, median year-ahead inflation expectations remained unchanged at 2.5 percent in March, while median three-year- ahead expectations dropped from 2.6 percent in February to 2.4 percent in March. Uncertainty about future inflation increased at both horizons.

The aggregate results for March conceal considerable within-month variation. Reflecting the steady expansion of the COVID-19/coronavirus outbreak, we see a gradual worsening in expectations over the course of the month. As shown in columns 3 to 6 of the table below, household income growth expectations continued to decline each week throughout the month. While initially more stable, household spending growth expectations exhibited a sharp decline in the third week of March. The average perceived risk of layoff continued to rise, while the probability of finding a job (given a job loss today) declined through March. At the same time, we observe a persistent deterioration during the month in respondents’ year-ahead outlook for credit availability and their overall household financial situation. Even though median inflation expectations were more volatile at both the one- and three-year horizons throughout the month, inflation uncertainty, as well as inflation expectations dispersion (not shown in table), showed a persistent increase at both horizons during March.

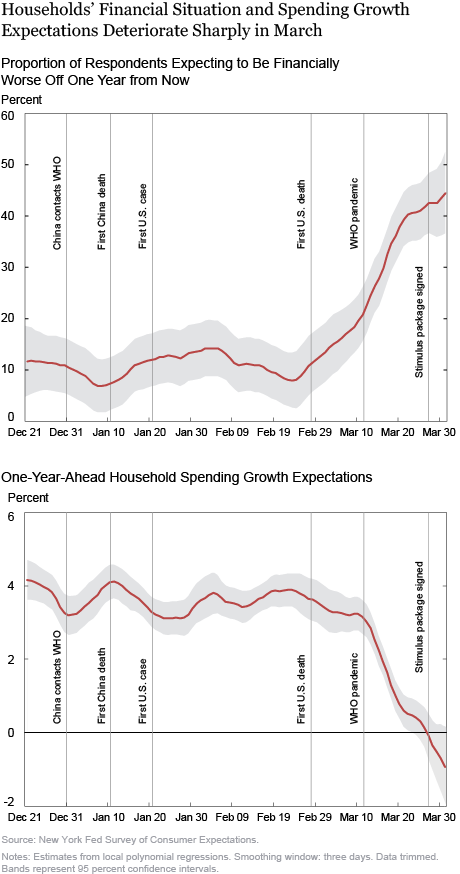

The chart below represents another way to look at how expectations evolved during March: It tracks the proportion of respondents who expect to be financially worse off a year from now and the median expectation for year-ahead spending growth. The trends shown here are derived from local polynomial regressions fitted to daily SCE responses using a three-day window. Note that the latter estimates do not target the median of the variable of interest, so some of the series’ patterns may not perfectly match the figures shown in the table. A chart packet showing trends for other outcomes can be found here. The chart clearly shows that most of the change in expectations started either after the first death from COVID-19 in the United States or around the time the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak a pandemic.

Further, as suggested by the chart and confirmed by the highlighted cells in the table above, by the last week of March many of the series had reached a new series (post-June 2013) high or low. Median household spending growth expectations trended into negative territory during the final week of March, more than 2 percentage points below their pre-March low, while the share of respondents expecting to be financially worse off a year from now increased sharply, climbing to well above 40 percent.

In a companion blog post due to be released on April 16, we will take a deeper dive into these data and analyze additional COVID-19-related information gathered in the March SCE.

Olivier Armantier is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gizem Kosar is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rachel Pomerantz is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rachel Pomerantz is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Daphne Skandalis is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Kyle Smith is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Giorgio Topa is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Giorgio Topa is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Olivier Armantier, Gizem Koşar, Rachel Pomerantz, Daphne Skandalis, Kyle Smith, Giorgio Topa, and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “Coronavirus Outbreak Sends Consumer Expectations Plummeting,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 6 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/04/coronavirus-outbreak-sends-consumer-expectations-plummeting.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics