Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) have grown steadily over the last two decades, becoming important providers of financial intermediation services. As NBFIs naturally interact with banking institutions in many markets and provide a wide range of services, banks may develop significant direct exposures stemming from these counterparty relationships. However, banks may be also exposed to NBFIs indirectly, simply by virtue of commonality in asset holdings. This post and its companion piece focus on this indirect form of exposure and propose ways to identify and quantify such vulnerabilities.

Why Monitor NBFIs?

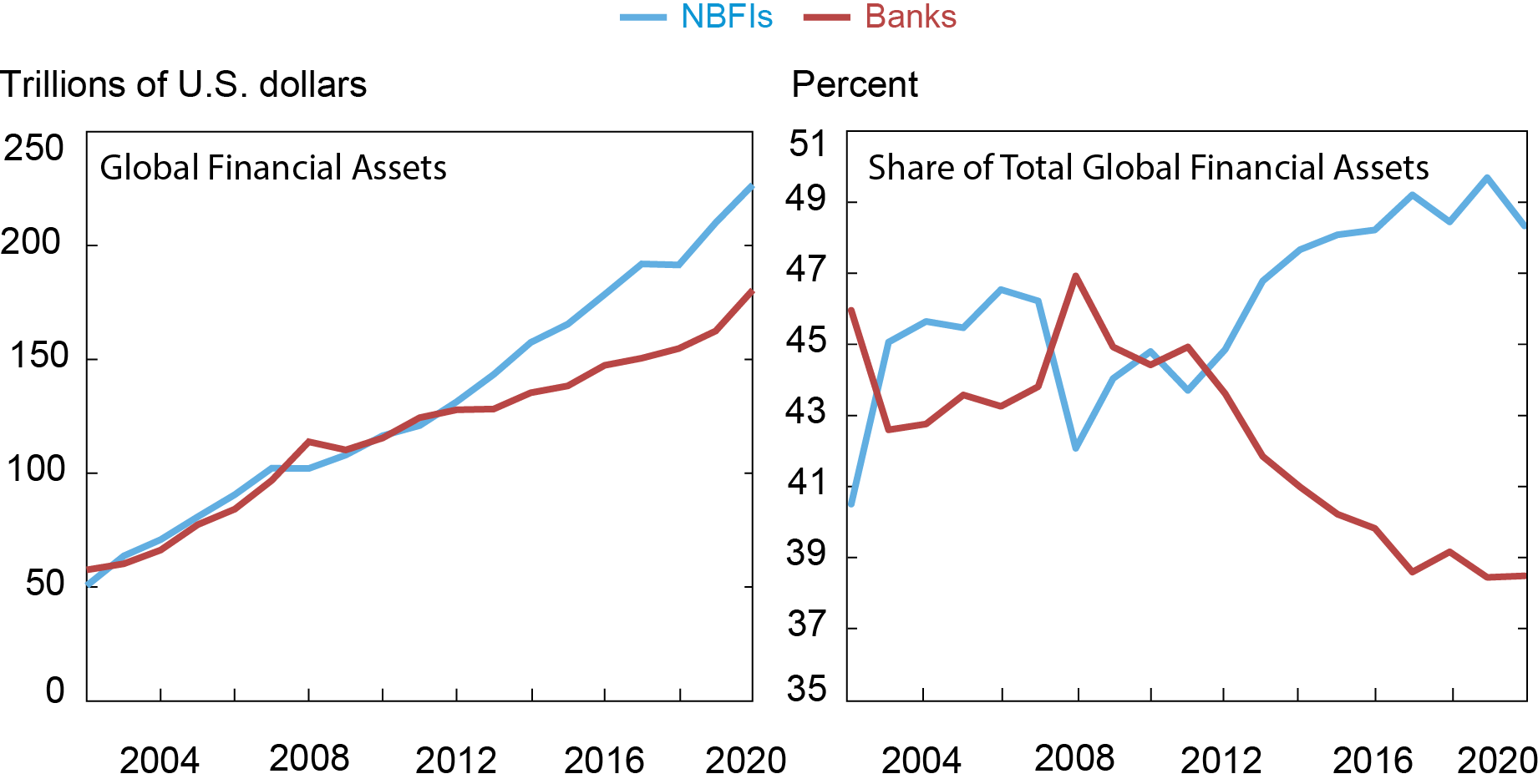

NBFIs have grown at a remarkable pace over the last twenty years and their growth was hardly affected by the major financial disruptions of 2007-08 and 2020. In the chart below, the lefthand panel shows the global scale of NBFIs’ aggregate financial assets and, for reference, the equivalent aggregate for banking institutions. Globally, NBFIs have grown at an average rate of 9 percent annually—higher than the growth rate of banks. The righthand panel shows that NBFIs’ share of total global financial assets has increased while that of banks has decreased in recent years. These trends would be qualitatively similar if we just focused on the United States.

NBFIs Have Outpaced Banks since the Global Financial Crisis

Notes: An NBFI is any financial institution that is not a central bank, bank, or public financial institution. Types of NBFIs include insurance corporations, pension funds, investment funds, captive financial institutions and money lenders, central counterparties, broker-dealers, finance companies, trust companies, and structured finance vehicles. The panel on the left reports the global size of the NBFI and banking sectors, in trillions of U.S. dollars. The panel on the right reports the size of the two sectors as a share of aggregate global financial assets, which also includes the assets of central banks and public financial institutions.

Banks and nonbanks can engage with one another through direct counterparty relationships. For example, nonbanks can be providers of both deposits and wholesale bank funding, while banks can have significant credit exposures to nonbanks. Indeed, such direct exposures have grown in recent years, and they can represent important vulnerabilities that impede the safety and soundness of banks.

However, the web of interactions between banks and nonbanks has grown increasingly more complex, so much so that banks may be vulnerable to nonbank activities extending beyond direct counterparty relationships. Specifically, banks can be exposed to nonbanks as they may jointly engage in a wide array of financial markets. For example, banks may be vulnerable to distress events affecting NBFI segments because they hold similar portfolios of financial assets as NBFIs. This results in the potential exposure of banks to a fire sale channel: when NBFIs experience distress, they are forced to sell a portion of their financial assets (that is, engage in fire sales), which may cause significant price dislocations for these assets, and thereby impose economic and/or accounting losses on banks that hold those same types of assets. Recently, one of us documented the importance of this kind of exposure for U.S. banks in the context of the COVID pandemic in March 2020. Identifying and tracking these exposures likely becomes more relevant as inter-connections between banks and NBFIs grow.

U.S. Bank Exposure to Fire Sales of Open-End Funds

In order to explore these issues and extract valuable monitoring insights, we conduct a quantitative study of the potential impact of open-end funds’ fire sales on U.S. bank holding companies. The methodology used to identify fire-sale spillovers is similar to that described in earlier work. Specifically, we hypothesize distress scenarios whereby open-end funds experience redemptions by their investors. Funds accommodate such hypothetical redemptions through the partial liquidation of their asset holdings. Such forced sales of assets, if conducted broadly across funds, would lower prices and thereby have an impact on other investors holding those same types of assets. Using data between 2010:Q1 and 2019:Q4 on individual asset holdings of the population of U.S. registered open-end funds, we quantify the extent of hypothetical fire sales and estimate the effect of the resulting price impact on the balance sheets of the top 100 U.S. bank holding companies.

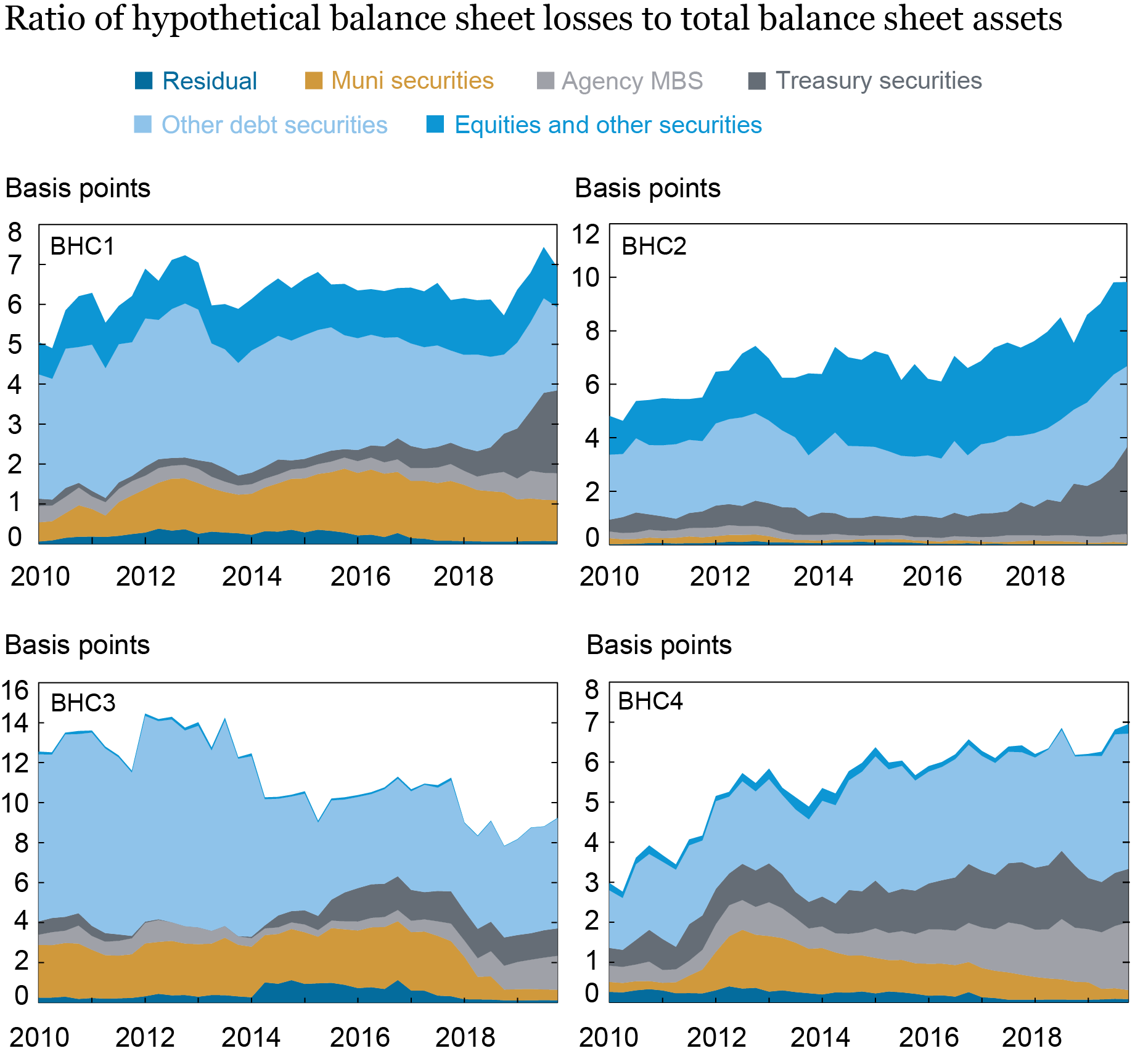

The chart below shows the hypothetical balance sheet losses experienced by four representative bank holding companies that were the subject of the study. The losses are expressed as a ratio to the dollar value of total balance sheet assets aggregated across all the affected asset classes. We do not suggest that these firms are especially exposed to this type of vulnerability, but instead view them as representative of the largest banks, whose business models are more likely to be more aligned with those of nonbanks.

Bank Holding Companies Have Heterogeneous Exposures to Funds’ Fire Sales

For each of these representative bank holding companies, the panels show the decomposition by asset class of the balance sheet losses as a fraction of their total assets (expressed in basis points) for each quarter between 2010:Q1 and 2019:Q4. Our analysis yielded three important new insights:

- Bank holding companies are differentially exposed to fire sale risks, as indicated by differences in the total potential losses they could sustain in the event of funds’ fire sales (as shown by the different scale of the losses across the four firms).

- These differences in the total scale of exposures reflect differences in total balance sheet size; bank holding companies’ vulnerabilities are heterogeneous across asset classes and reflect the concentration of holdings and the relative conditions of the markets where such assets are traded.

- This is a reflection of different business models chosen by the banks, which in turn are reflected in different choices of the type of assets held and their proportions; there is considerable variation in the time series as a result of changes in relative market conditions, and differential trends followed by the four firms in their asset size and portfolio composition.

Insights into Monitoring NBFIs

These results imply innovative insights for monitoring NBFIs: (a) monitoring of direct exposures may not be sufficient, as risks from indirect channels of exposure can be significant during periods of stress; (b) these exposures are likely heterogeneous across bank holding companies, with the heterogeneity likely driven by differences in business models.

Of course, the picture could be even more complex than that, once we take into account the simultaneous presence in the same markets of other nonbank types, besides just funds. The next post enriches the analysis of indirect exposures by highlighting important network interconnections among banks and twelve different NBFI segments.

Nicola Cetorelli is the head of Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Debashish Sarkar is a capital markets risk principal examiner in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Supervision Group.

How to cite this post:

Nicola Cetorelli and Debashish Sarkar, “Enhancing Monitoring of NBFI Exposure: The Case of Open‑End Funds,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 18, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/04/enhancing-monitoring-of-nbfi-exposure-the-case-of-open-end-funds/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics