Evidence from a 160-year-long panel of U.S. banks suggests that the ultimate cause of bank failures and banking crises is almost always a deterioration of bank fundamentals that leads to insolvency. As described in our previous post, bank failures—including those that involve bank runs—are typically preceded by a slow deterioration of bank fundamentals and are hence remarkably predictable. In this final post of our three-part series, we relate the findings discussed previously to theories of bank failures, and we discuss the policy implications of our findings.

Distinguishing Bank Runs from Insolvency Using Historical Data

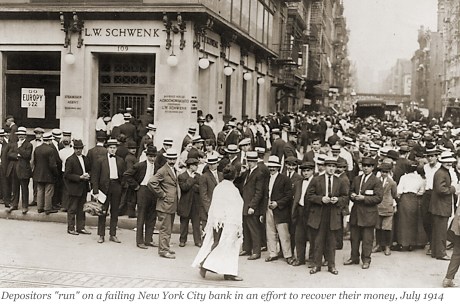

Banks fail either because of bank runs or because of insolvency. However, it is difficult to distinguish between these causes empirically using contemporary data, as government interventions such as deposit insurance and lender of last resort authority make self-fulfilling liquidity-driven failures less likely in modern banking systems. A common argument in favor of these interventions is that they prevent failures caused by runs, especially on healthy banks. Thus, observed bank failures in modern times may be biased toward failures involving poor fundamentals.

Our historical dataset, which goes back as far 1865 and is described in detail in this new working paper, enables us to overcome this important challenge by allowing us to analyze failures that occurred before the founding of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), when all depositors typically realized losses in bank failures and bank runs were hence a more plausible explanation for why banks fail.

Three Testable Predictions of Theories of Bank Runs

There are three testable empirical implications of theories of bank runs. Specifically, for a run to be the cause of a bank failure:

- Deposits must actually flow out of the bank before failure. In standard theories of bank runs, deposit outflows erode solvency by forcing banks to either liquidate their otherwise valuable assets or replace deposit funding with more expensive wholesale funding. Hence, if a bank fails with only a minimal decline in deposits, it is unlikely that deposit outflows have induced the bank to engage in actions that reduce solvency, so a bank run is unlikely to be the cause of failure.

- Loss rates on a bank’s assets in failure cannot be too high if the bank failed due to the run (and the bank would have survived absent the run). Unlike nonfinancial firms, which hold assets that are considerably more valuable inside the firm than outside the firm, banks largely hold assets that can be separated and repossessed, such as securities and loans. Hence, recovery rates on assets held in bankruptcy should be relatively high if a bank failure is caused by a bank run on an ex ante solvent bank. By and large, the scope of a bank run to destroy value stems from destroying a bank’s franchise value, not from reducing the value of assets still held after bank closure.

- The predictability of failure should at best be modest. In theoretical models, bank failures are either entirely unpredictable due to “sunspot” panic runs (as in the celebrated work of Diamond and Dybvig, which was awarded the Nobel prize in 2022), or bank runs are weakly predictable, as depositors respond immediately to signals of distress—making it very difficult to predict future run-induced failures. Hence, in order for runs by attentive depositors to bring down a weak but solvent bank, the bank’s predicted probability of failure before failure cannot be too high.

Evidence from Pre-FDIC Bank Failures

In Correia, Luck, and Verner (2024), we analyze the distribution of pre-FDIC bank failures across these three factors: deposit outflows, asset recovery rates, and failure predictability based on weak fundamentals. As outlined above, for a bank run to be a plausible cause of failure, a bank must actually experience substantial deposit outflows, have a relatively high asset recovery rate, and have low to modest predicted probability of failure. We therefore ask how many bank failures satisfy these criteria.

We find that bank runs can be rejected as a plausible cause of failure in more than 80 percent of pre-FDIC bank failures. While many banks had large deposit outflows right before failure, these deposit outflows are most likely a consequence of weak fundamentals and banks most likely would have also failed absent the run. In particular, most banks with large deposit outflows had very large asset losses in failure, on the order of about 45 percent. Furthermore, these banks typically also had a high predicted probability of failure right before failure, often above 10 percent, indicating that their fundamentals were very weak. Said differently, relatively few historical bank failures experienced large deposit withdrawals, had low to moderate predicted probability of failure, and ended having a high recovery rate on their assets (exceeding 75 percent).

Our findings imply that it is unlikely the case that bank runs that bring down otherwise healthy banks no longer occur because of deposit insurance, but rather that such runs were hardly an empirically relevant cause of bank failures to begin with. Moreover, while we do find instances of weak banks that could have been plausibly solvent absent a run, we also document that they are relatively uncommon. By far the most plausible cause of the majority of failures in the history of the U.S. banking system are asset losses and deteriorating solvency, and failure would have likely occurred even in the absence of deposit outflows.

Our assessment is in line with that of contemporary bank examiners from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). The next chart shows the OCC-classified causes of failure for bank failures between 1865 and 1939. The most common causes are economic conditions (such as a crop loss or local economic depression), asset losses, and fraud—all factors related to deteriorating fundamentals. In contrast, despite popular narratives about banking panics playing a key role in the historical U.S. banking system, runs and liquidity issues account for less than 2 percent of failures classified by the OCC.

Causes of Failure as Classified by the OCC for Failures Between 1865 and 1937

Share of all failures (percent)

Notes: Causes of failure are as classified by the OCC in the tables of national banks in charge of receivers from the OCC’s Annual Report to Congress for various years. We categorize the detailed list of failure reasons as described in Correia, Luck, and Verner (2024). The OCC’s classification data is essentially complete for failures from 1865-1928, partially complete for failures from 1929-1931 and 1934-1937, and entirely missing for failures in 1932 and 1933.

Depositor Inattentiveness Before Deposit Insurance

The high degree of predictability of bank failure raises a final puzzle: Why don’t bank runs occur earlier than they do? We find that a substantial share (23 percent) of failed banks had an extremely high predicted probability of failure (exceeding 20 percent) right before failure. This predicted probability is based on public information available to contemporaries at the time. Hence, in principle it would have been easy for investors to identify weak banks. But it is difficult to imagine that a bank could be viable if it had to compensate its depositors for such a high risk of failure, especially since depositors faced loss rates averaging about 30 percent in the typical bank failure. Nonetheless, by construction, these banks, despite having a very high probability of failure, haven’t failed yet. Therefore, our findings suggest that depositors are often sleepy and slow to react to an increased risk of failure, even in the era before deposit insurance. This depositor sleepiness could be due to behavioral factors such as inattention or neglect of downside risks.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

Using data on more than 37,000 banks and 5,000 bank failures in the U.S. from 1865-2023, our analysis suggests that the ultimate cause of bank failures and banking crises is almost always a deterioration of bank solvency. This deterioration is typically gradual, taking place over several years. During those years, the realization of credit risk reduces income and erodes capital buffers, pushing banks slowly toward the brink of default. At times, the deterioration of a bank’s solvency is preceded by a boom phase during which failing banks likely take more risks at the margin than their peers. The erosion of a bank’s profitability and capitalization ultimately results either in a bank run or a supervisory decision to close the bank, with the former being more common before the FDIC. Importantly, both depositors and supervisors seem to be slow to react to information about bank fundamentals, thus making bank failures highly predictable.

Our findings have several important policy implications. First, the predictability of bank failures implies a role for ex ante interventions to prevent bank failures or mitigate their damage. The fact that bank failures are predictable supports the prompt and active use of corrective measures, such as limiting dividend payouts and the use of noncore funding for poorly capitalized banks. More generally, our findings emphasize the importance of requiring financial intermediaries to be well-capitalized. Our findings also imply that ex post interventions during a crisis must address fundamental solvency issues. Policies that backstop liquidity without addressing insolvency are unlikely to be sufficient for mitigating the costs of bank failures.

Sergio Correia is a principal economist in the Financial Stability Division at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Stephan Luck is a financial research advisor in Banking Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Emil Verner is an associate professor of finance at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

How to cite this post:

Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner, “Why Do Banks Fail? Bank Runs Versus Solvency,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, November 25, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/11/why-do-banks-fail-bank-runs-versus-solvency/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics