In its September 20, 2017, statement, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) said that, beginning in October 2017, it would initiate the balance sheet normalization program described in the June 2017 addendum to the Committee’s Policy Normalization Principles and Plans. Specifically, to reduce the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings, the FOMC directed the New York Fed’s Trading Desk (“the Desk”) to reinvest each month’s principal payments from Treasury securities, agency debt, and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) only to the extent that such payments exceed gradually rising caps. This policy implies that the size of the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings will decline in a gradual and predictable manner over time. In this post, we describe the mechanics of this process for agency MBS and explain why predicting the precise evolution of the size of the MBS portfolio is more difficult than it is for Treasury securities.

The initial redemption caps (meaning the maximum amount the portfolio is allowed to shrink in a month) were set at $6 billion for Treasury securities and $4 billion for agency securities; the FOMC expects to increase these caps every three months. A schedule consistent with the Committee’s normalization plan is outlined in the Desk’s Statement Regarding Reinvestment in Treasury Securities and Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities. The process of reducing the size of the System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio is thus currently under way and can be monitored by studying the H.4.1 statistical releases, in which detailed information about the SOMA, along with the Federal Reserve’s entire balance sheet, is publicly reported each Wednesday.

Treasury securities in the SOMA portfolio mature at fixed dates, and settlement from rollover purchases occurs on the same day as the maturity, making changes in the size of the SOMA Treasury holdings relatively smooth and predictable. In contrast, for agency MBS, principal payments from existing holdings are not received on the same days of the month that reinvestments of new MBS settle, resulting in intramonth variability in the size of the agency MBS portfolio. Moreover, principal payments on agency MBS reflect two factors—scheduled principal repayments and unscheduled principal prepayments. The unscheduled component that reflects homeowners choosing to prepay part or all of their principal balance at their discretion introduces cash flow uncertainty for MBS investors. This uncertainty surrounding agency MBS principal payments, combined with the forward-settling nature of the agency MBS market, drive a lag between when principal payments are received and when settlements of purchases occur. These factors are covered in greater detail below.

Principal Payment Uncertainty

Agency MBS investors face considerable uncertainty with respect to the timing of principal payments they receive. Homeowners with fixed-rate mortgages make payments each month that consist of interest and principal, and these payments get passed through to MBS holders. Principal is paid off at a predetermined amortization schedule; however, the borrower has the option to pay down any additional amount of the mortgage principal at any time (this usually occurs because the borrower refinances the mortgage or sells the home). As a result, holders of agency MBS don’t know with certainty how much principal they will receive in a given month. In fact, investors don’t receive preliminary estimates of a month’s principal paydowns until the fourth business day of the month, because it takes time to calculate, verify, and report the mortgage payments.

Because monthly principal payments aren’t reported until after the month begins, the Fed conducts its monthly reinvestment purchases on a midmonth-to-midmonth basis. So despite the fact that the FOMC expresses a monthly redemption cap, monthly MBS reinvestments don’t actually occur on a calendar month basis.

To illustrate how prepayment uncertainty affects the timing of reinvestments, consider October 2017, the first month for which caps were in effect. The principal paydowns received in October totaled $24 billion; after applying the $4 billion cap, the Fed had around $20 billion of principal to reinvest. The Desk then purchased $20 billion of agency MBS over the monthly period spanning October 16 through November 13. Therefore, prepayment uncertainty causes delays in the calculation and reinvestment of monthly principal payments for the Desk.

Forward Settlement of MBS Transactions

When purchasing agency MBS, the Desk transacts on a forward basis in what is known as the to-be-announced (TBA) market. Settlement dates for TBAs are determined by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA); SIFMA publishes this information on its website. Settlement for each security class (Class A includes thirty-year Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac MBS, Class B includes fifteen-year Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac MBS, and Class C includes Ginnie Mae thirty-year MBS) takes place once a month and trading typically occurs up to three months forward.

For the October purchase period mentioned above ($4 billion agency MBS cap and $20 billion of reinvestment purchases), the Desk purchased a portion of the $20 billion in TBAs for settlement in November and some for settlement in December (historical operational results are released monthly). Since the Fed uses settlement accounting for all purchase activity—meaning purchases aren’t recorded until settlement—the $4 billion cap that was announced in September and applied to October paydowns didn’t affect the balance sheet until mid-November and mid-December, when purchases settled. (Unsettled trades are reported as supplemental information in the weekly H.4.1 release.) Similarly, the $4 billion cap applied to November paydowns began to be reflected in mid-December and won’t be fully reflected in the H.4.1 until the end of January, and so on.

All told, there is as much as a three-month lag from when principal is received (resulting in a reduction in holdings) and when the corresponding new MBS are added to the balance sheet (resulting in an increase in holdings). Of note, occasional “dollar roll” sales—a tool that the Desk uses to facilitate settlement—can extend settlements even further.

Timing Difference between Settlements from Prior Purchases and Principal Receipts

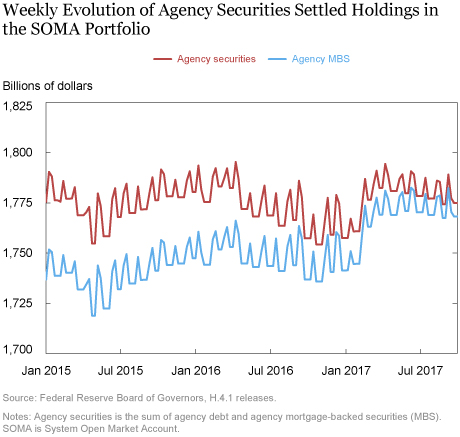

Another complicating factor is that the arrival of principal payments on MBS held in the SOMA portfolio is not synchronized with the settlements of purchases made in previous months. Agency MBS principal payments are received on the fifteenth, twentieth, and twenty-fifth of the month for Freddie Mac, Ginnie Mae II, and Fannie Mae securities, respectively; but while settlements of reinvestment purchases also occur three times a month, they take place on different dates (see the SIFMA settlement dates calendar linked to above). Because receipts of principal do not occur at the time of principal reinvestments, the amount of agency MBS holdings in the SOMA portfolio varies throughout the month, which is illustrated by the jagged appearance of agency MBS data when viewed as a time series (see chart below). Of note, agency securities include both agency MBS and agency debt; agency debt is reinvested in MBS when it matures.

In October 2017, for example, MBS inflows and outflows took place on six different days, with three of the days representing principal paydowns (MBS outflows) and three representing settlements from previous purchase cycles (MBS inflows). This staggering of cash flows results in the reported MBS portfolio rising and falling throughout the month, and can make it difficult to see, in the short run, MBS settled holdings decline (see chart below).

Summing Up

In sum, the gradual reduction of the SOMA agency MBS portfolio will occur with a lag because of the uncertainty surrounding principal payments and the forward-settling nature of the TBA market. Moreover, the misalignment in the timing of principal payments and settlements causes week-to-week variation in SOMA holdings, which can obscure the longer-term trend in those holdings.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Andreas Fuster is an officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Brian Greene is a policy and market analysis manager in the Bank’s Markets Group.

Brett Rose is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Markets Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Andreas Fuster, Brian Greene, and Brett Rose, “Balance Sheet Normalization: When Will Agency MBS Holdings Decline?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), January 8, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/01/balance-sheet-normalization-when-will-agency-mbs-holdings-decline.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics