The higher education landscape changed drastically over the last decade and a half. This evolution was largely characterized by the unprecedented growth of the private for-profit sector. In this post, we examine whether the evolution of the higher education market was associated with changes in the types of students who attended the institutions in various sectors of the market. Was the growth in enrollment spurred by an increased entry of traditional students? Or was it driven by an inflow of nontraditional students? Has student composition in higher education changed differentially between sectors? It is important for us to understand not only the growth in the higher education market but also which types of students contributed to this growth, because any changes in the composition of students may have implications for the composition of skilled workers in the labor market, for student loans, for loan repayment, and for the labor market returns to education investments.

Part-Time Students

Among students studying at public two-year and less-than-two-year institutions between 2000 and 2015, our analysis shows that more than 60 percent were part-time. The comparable figure for students at for-profit schools is only 13 percent (less than one-quarter the public number). However, as we saw in our opening post in this series, the vast majority of students studying at two-year and less-than-two-year institutions study at public schools. Taken as a whole, then, more than 57 percent of all students studying at two-year and less-than-two-year institutions were part-time. This share of part-time students decreased gradually, from 60 percent in 2000 to 54 percent in 2011, but post-recession years have seen an increase back to 58 percent in 2015.

Broadly speaking, students at four-year institutions have been much less likely to be part-time—just 21 percent of students in this sector were part-time between 2000 and 2015. However, there were large differences across the various categories of four-year institutions. Elite private schools and public flagship schools had a much lower percentage of part-time students than the other categories, with the share at elite private schools decreasing to just 5 percent in 2015. Between 2000 and 2011, the percentage of part-time students at most categories of four-year schools stayed relatively constant, before witnessing a slight uptick in the post-recession years.

Public nonflagship institutions have generally been increasing their share of part-time enrollees, but the truly striking development is the aggressive expansion of the for-profit schools into the part-time market. It is clear that for-profit schools are achieving much of their growth by catering to a new type of student. For-profit schools increased their share of part-time enrollees by 70 percent between 2006 and 2015, from 20 percent of enrollment to 34 percent. The rest of the four-year institutions stood at 22 percent part-time students in 2015, far below the for-profit schools. Moreover, the expansion of part-time students at for-profit colleges shows little sign of abatement, increasing from 31 percent of enrollment to 34 percent between 2012 and 2015 alone.

Older Students

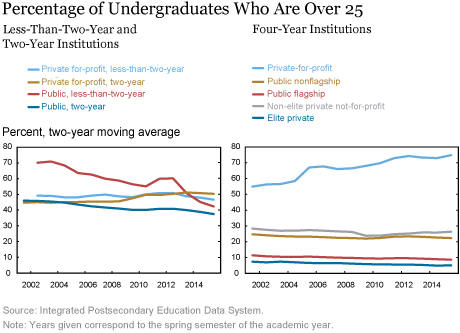

An examination of the percentage of undergraduates over age twenty-five reveals similar post-recession patterns (see the chart below). Each of the sectors in the two-year and less-than-two-year market saw an increase in the enrollment of older students in the aftermath of the financial crisis, possibly reflecting young workers (who equate to older students) returning to school after being laid off or struggling to find appropriate work. Notwithstanding this uptick, public schools experienced a decrease in their share of older students from 2000-15, while for-profit schools increased their share of nontraditional older students.

Generally speaking, the share of older students at four-year institutions has remained fairly constant over the period being studied. The major exception to this, as the chart above illustrates, is that for-profit institutions are aggressively increasing the share of older undergraduates enrolled. In 2000, the share of older students at for-profit schools dwarfed the share in all other types of schools—55 percent to 23 percent, respectively—and this gap continued to widen through 2015.

Female Students

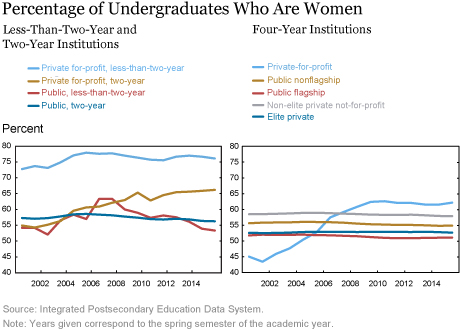

Among both two-year and less-than-two-year institutions, for-profit colleges have a higher percentage of female undergraduates (see the chart below). Indeed, from 2000 to 2015 for-profit schools consistently increased their share of female students, while public schools had roughly the same share in 2015 that they did in 2000. Across all two-year and less-than-two-year institutions, a sizable majority of students are female—in 2015, more than 57 percent.

While the proportion of female students has generally held steady in the two-year and less-than-two-year institutions since 2000, it’s been a very different story in the four-year, for-profit institutions. Though for-profit schools were male dominated in 2000, between 2000 and 2008 they rose from 45 percent female to 61 percent female—much more than any other category of four-year schools. Interestingly, this rapid relative growth of women was primarily a pre-recession trend. From 2008 to 2015, the share of female undergraduates at four-year, for-profit schools hardly changed (totaling 61 percent in 2008 and 62 percent in 2015).

Federal Pell Grant Recipients

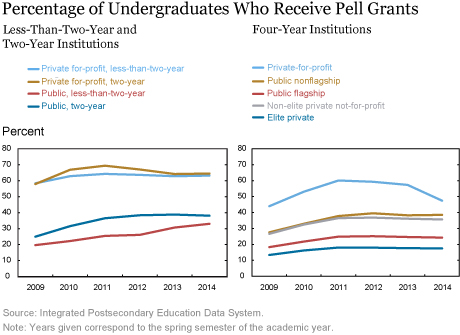

Federal Pell grants are generally directed toward students who have not previously received a bachelor’s degree. They are awarded to low-income students with a demonstrated financial need, and thus are a good barometer for a student’s level of income. As the chart below shows, among students at two-year and less-than-two-year institutions, students at for-profit schools are much more likely to have received Pell grants. In 2014, for instance, 58 percent of students studying at for-profit, two-year or less-than-two-year schools received Pell grants, while only 38 percent of their peers at public schools were recipients of these grants. Across all institution types in the two-year and less-than-two-year sector, the percentage of students receiving Pell grants has increased in the post-recession years.

Much as with the two-year and less-than-two-year institutions, students at four-year, for-profit institutions are much more likely than their peers at other four-year institutions to receive Pell grants. This again points to the fact that for-profit institutions cater to lower-income students (relative to the other sectors). The share of students at for-profit institutions receiving Pell grants peaked in 2011 at 60 percent; that same year, only 35 percent of students at all other four-year institutions were Pell recipients. As the above chart shows, the number of Pell recipients in for-profit schools grew dramatically in the years immediately following the recession, from 44 percent in 2009 to 60 percent in 2011, and the growth rate began to taper starting in 2011.

Minority Students

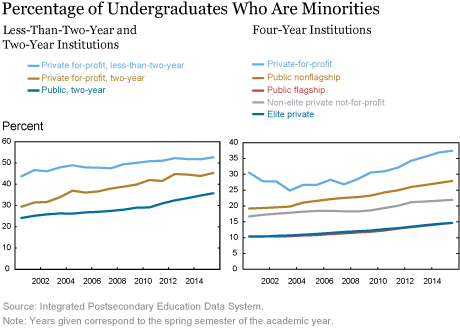

Across all types of two-year and less-than-two-year institutions, our analysis reveals that the percentage of under-represented minority (black and Hispanic) students has been steadily rising since 2000 (see the chart below). These trends do not appear to have been affected by either the boom years or the years following the most recent recession. In 2009, the student populations of less-than-two-year, for-profit institutions became more than 50 percent minority.

Similar to the trend at less-than-two-year and two-year institutions, the percentage of minority students at four-year institutions has been increasing each year since 2000. The percentage of minority students at four-year, for-profit institutions, however, did seem to react to the most recent recession. Since 2007, the percentage of minorities at these schools has increased at a much faster rate than at other types of four-year institutions. In each year since 2000, for-profit schools have had a larger percentage of minority students than any other type of four-year school.

Conclusion and a Look Ahead

The above discussion shows that the post-recession enrollment spurt has been driven mainly by nontraditional students. Proportionately more part-time students, relatively older students, female students, and minority students entered the higher education market in the post-recession period, and this pattern is most prominent in the private for-profit sector, the sector that led the growth in this period. (The only exception is that the four-year, for-profit enrollment growth in the post-recession period was driven proportionately more by men than women.) This drastic change in the composition of the higher education market in the post-recession period, and especially in the for-profit sector, may very well have broader implications for the composition of the skilled labor force in the near future. There may also be implications for earnings and student-debt management, and by extension for growth in the national economy. To foster understanding of some of these effects, our series will continue with two blog posts that will focus on student loans, graduation, and default during this period.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael Lovenheim is an associate professor at Cornell University and a faculty research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kevin Morris is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Rajashri Chakrabarti, Michael Lovenheim, and Kevin Morris, “The Changing Face of the Higher Education Market,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), September 7, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/09/the-changing-face-of-the-higher-education-market.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics