Estimates from the Current Population Survey show that the probability of finding a job declines the longer one is unemployed. Is this due to a loss of skills from being unemployed, employer discrimination against the long-term unemployed, or are there characteristics of workers in this segment of the workforce that lower their probability of finding a job? Studies that send out fictitious resumes find that employers do consider the length of unemployment in deciding whom to interview. Our recent work examines how such employer screening based on unemployment duration ultimately affects job-finding rates and long-term unemployment.

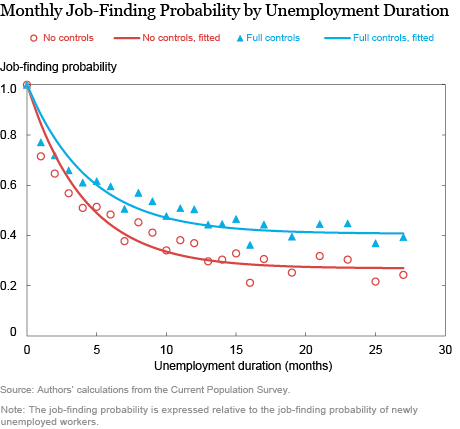

In the chart below, the solid red line plots the probability of finding a job by unemployment duration relative to the job-finding rate for the newly unemployed. The job-finding rate declines by roughly 50 percent within eight months. This negative relationship continues to hold even when we control for various observable characteristics such as age, race, education, and gender to prevent composition bias. For example, less educated workers have lower job-finding rates than more educated workers, remain unemployed for longer, and become overrepresented in the pool of long-term unemployed, which mechanically lowers the job-finding rate in the population. Controlling for education therefore flattens out the relationship between job-finding rates and unemployment duration (as seen in the blue line below), though a significant decline remains.

However, we cannot control for unobservable worker characteristics: diligence, personality, or other, softer skills that matter for one’s performance at work. Think about all of the attributes that are revealed in an interview that are not reflected on a resume. If these qualities are important for finding a job and we could measure them, we might plot yet another curve that would lie above the blue curve. The question is whether there are other reasons the job-finding rate might fall the longer one is unemployed that go beyond a person’s skill set?

One possibility is employer discrimination. Indeed, researchers using a resume audit study approach have found that employers are less likely to follow up on applications from workers who have been out of work for longer periods. Audit studies respond to job advertisements with fictitious resumes in which they only vary the length of time the person has been out of work, and then track callbacks for interviews. These experiments find that long-term unemployed workers can be up to 45 percent less likely to receive interview invitations than newly unemployed or currently employed people who look just like them.

However, we cannot infer that 45 percent of the decline in the job-finding rate is caused by employer discrimination, even if interview invitations decline by 45 percent with unemployment duration. Why? Suppose that unemployment duration is correlated with unobservable characteristics (the very ones we cannot measure), and firms use unemployment duration as a way of inferring the unobservables that are likely to be associated with that particular job candidate. To economize on interview costs, firms may turn down resumes belonging to workers who they expect will likely be turned down after a costly and time consuming interview.

In this event, the reluctance of firms to interview the long-term unemployed can result in two outcomes. First, some workers’ resumes will be dismissed who would not have been hired, even if an interview had been conducted (group 1). Second, some long-term unemployed would have been hired if given the opportunity to interview (group 2). Measuring the impact of employer discrimination on job-finding rates requires quantifying how many people fall in these two distinct groups—it is those falling into the latter group who suffer a meaningful change in their ability to find a job.

Although audit studies control for unemployment duration, they cannot control for the unobservables that are correlated with it. They thus cannot tell how many workers fall in each of the two groups. To address the issue, we develop a structural model of the labor market that is qualitatively consistent with, and quantitatively disciplined by, empirical evidence on job-finding rates and employer discrimination in callbacks. That is, running an audit study experiment inside our model produces comparable declines in interview invitations to those found in real-world experiments. Importantly, though, the model knows the unobservables behind every resume. It can therefore divide the applicants into the two relevant groups, enabling us to quantify the extent to which employer discrimination affects job-finding rates and long-term unemployment.

In our framework, workers apply to job openings by sending out resumes and firms can review the resumes before deciding whom to interview. The key idea is that there is some “unobserved” component of worker quality that cannot be listed on a resume that is revealed in a job interview, and that is valuable to employers. Conditional on an interview, workers with highly desirable qualities get hired quickly because their type is revealed to employers. Firms anticipate that they will be less likely to find a suitable candidate among the long-term unemployed and respond by interviewing the long-term unemployed less frequently.

In our estimated model, we quantify the effects of employer discrimination in callbacks—on job-finding rates and long-term unemployment—by conducting two experiments. In the first, we simulate a world in which interviews are free, so all workers are invited for interviews, regardless of their unemployment duration. In the second, we restrict the firm’s interview decision to be independent of unemployment duration (a ban on discrimination). We compare the outcomes in these counterfactuals to the true economy, which features discrimination, and find that job-finding rates at all durations and the incidence of long-term unemployment differ only marginally.

Why is this the case? The majority of the long-term unemployed in our estimated model fall in the group that would not be hired after an interview, suggesting that the observed discrimination in callbacks is a rational response to statistical probabilities. Firms only interview an applicant if they believe there is a sufficiently high likelihood that they may hire them. If employers are getting it right, then only a few of the job candidates not invited due to their unemployment duration would have succeeded. This implies that the consequences of employer discrimination at the interview stage on the hiring rate for the long-term unemployed are quite limited.

There are many other potentially important drivers of why the long-term unemployed are not hired, like skill loss in unemployment or discouragement in the face of weak job prospects. Our analysis of the limited consequences of discrimination suggests focusing on policies that target these types of concerns will be more effective in combating the plight of the long-term unemployed.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Gregor Jarosch is an assistant professor of economics at Stanford University.

Laura Pilossoph is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Laura Pilossoph is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Gregor Jarosch and Laura Pilossoph, “The Reluctance of Firms to Interview the Long-Term Unemployed,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), August 3, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/08/the-reluctance-of-firms-to-interview-the-long-term-unemployed.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics