How will the U.S. economy emerge from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic? Will it struggle to return to prior levels of employment and activity, or will it come roaring back as soon as vaccinations are widespread and Americans feel comfortable travelling and eating out? Part of the answer to these questions hinges on what will happen to the large amount of “excess savings” that U.S. households have accumulated since last March. According to most estimates, these savings are around $1.6 trillion and counting. Some economists have expressed the concern that, if a considerable fraction of these accumulated funds is spent as soon as the economy re-opens, the ensuing rush of demand might be destabilizing. This post argues that these savings are not that excessive, when considered against the backdrop of the unprecedented government interventions adopted over the past year in support of households and that they are unlikely to generate a surge in demand post-pandemic.

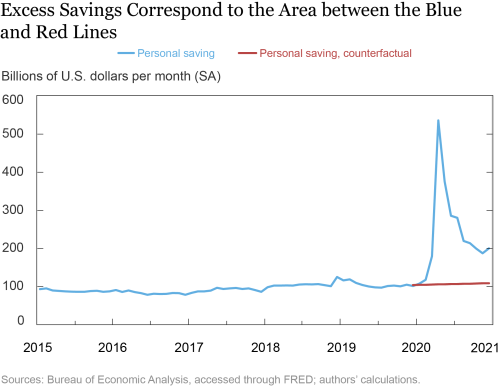

Calculating excess savings is simple: they are the cumulative amount by which personal saving during the pandemic has exceeded a counterfactual path without COVID-19. As shown in blue in the chart below, personal saving has been elevated since last March. The red line represents one plausible counterfactual scenario, in which the saving rate out of disposable income is constant at its pre-pandemic level (7.3 percent), while disposable personal income grows at its average rate over the previous twenty years (3.5 percent). Excess savings are the area between the two lines. According to this calculation, they amounted to $1.6 trillion as of December 2020. Different plausible assumptions on the counterfactual evolution of personal saving in the absence of the pandemic lead to relatively small differences in this headline number.

Where do these excess savings come from? Three contributing factors are clear. First, many Americans have thankfully kept their jobs and incomes over the past year. However, they have not spent nearly as much as they would have otherwise, because they are not dining out or going on vacation due to the pandemic. Increased purchases of furniture, electronics, and other goods have compensated only in part for this reduced spending on services. As a result, overall consumption has fallen for many households, even if their income is more or less intact. Second, starting with the emergency response approved in early March and the subsequent CARES Act, the government has stepped in to replace some of the lost income, especially for workers in the sectors hardest hit by the pandemic. Some of this income support was spent to keep food on the table and a roof over the heads of many families, but not all of it was. Third, it is possible that households decided to save more than usual as a precautionary measure, given the great uncertainty about their jobs and the overall health of the economy going forward.

Regardless of the precise reasons, there is no doubt that households saved more in the past year than they would have in a world without the pandemic. But is there anything “excessive” about the savings that they have thus accumulated? Are these moneys significantly different from the other $130 trillion in net worth that U.S. households already own, in a way that might lead them to be spent faster than other components of wealth? There are at least three reasons to think that the answer to this question is no.

Excess savings are the accounting counterpart of “extra” government debt. According to the principles of national income accounting, the flow of private saving (by households and businesses) must be channeled to one of three uses. It can finance investment, be lent abroad, or lent to the government. In 2020, the U.S. government spent roughly $2 trillion to fight the COVID-19 recession, most of it financed with debt. The $1.6 trillion in “excess savings” is the accounting counterpart of this increase in government borrowing.

As is often the case with accounting identities, this observation has limited economic implications. It does not reveal why households accumulated the “excess savings,” nor whether they will spend them once the economy fully re-opens. Nonetheless, it helps us to consider them under a different light—not as “extra” resources ready to be spent, but as the flip side of the extraordinary fiscal effort to fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

Excess savings are mostly held by…savers. One reason why many economists do not associate the exceptional increase in government debt over the past year with an imminent explosion in aggregate demand—even though they might worry about it for a host of other reasons—is the idea that government debt is money that citizens owe to themselves. As such, it would not represent “net wealth” that is ready to be spent. In economics jargon, this idea is known as Ricardian Equivalence. According to this proposition, public transfers financed with government debt do not affect consumption because households save them to pay for the increase in taxes that will eventually be necessary to repay that debt. If Ricardian Equivalence held, the marginal propensity to consume out of debt-financed transfers would be zero, and the resulting savings would never be spent.

Ricardian Equivalence is the kind of theoretical benchmark that economists love, but it clearly does not hold in practice. In fact, many U.S. families did spend a significant share of the checks and other income support that they received during the pandemic. According to available estimates, this share is around one-third on average. The rest was used to pay down debt (also about one-third) or otherwise saved. It is hard to know exactly who holds these savings, but it seems reasonable to assume that they are individuals and families with a bit of a buffer in their budgets—and whose consumption decisions are therefore less sensitive to their immediate economic circumstances. This is presumably what allowed them to save part of the support they received. According to economic theory, these savers are more likely to be Ricardian, and hence to continue holding on to these savings. Of course, their economic circumstances might change in the future and they might find themselves in need to spend those accumulated resources, but the end of the pandemic in itself is unlikely to turn them from savers to immediate spenders. If anything, fewer households should face financial hardship as aggregate conditions improve.

Excess savings are unlikely to unleash pent-up demand for services. One caveat to the previous reasoning is that some of the “excess savings” might be due to a dearth of spending opportunities in the sectors of the economy most affected by the virus, such as travel and entertainment. If this is true, some of that lost spending could materialize once those sectors fully re-open.

How large is this “pent-up” demand for services likely to be? On the one hand, there is little doubt that many consumers will enjoy a few extra restaurant meals and perhaps splurge on a nicer vacation after such a long period without them. On the other hand, there is a limit to how many extra restaurant meals and vacations people will be able to enjoy. To have a sense of how much of this pent-up demand might be activated by the “excess savings” accumulated during the pandemic, recall that available estimates of the propensity to consume out of the CARES Act transfers is about one-third. This means that the average household spent about 33 cents out of each dollar received in direct payments. As it turns out, this estimate is in line with those based on previous transfers of this kind, such as the Economic Stimulus Payments of 2008. Therefore, the pandemic does not seem to have substantially limited households’ ability to spend the support that they received.

The bottom line from these three sets of considerations is that, although large by historical standards, the savings accumulated by U.S. households during the pandemic do not appear to be “excessive” when set against the extraordinary need of many American families and the unprecedented government intervention to support them. It is certainly possible that some of these savings will pay for extra travel and entertainment once the COVID-19 nightmare is behind us, but our conclusion is that the resulting boost to expenditures will be limited. This conclusion does not rule out a strong economic recovery from the virus shock. It only implies that spending out of excess savings won’t be one of its major drivers.

Florin Bilbiie is a professor of economics at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland.

Gauti Eggertsson is a professor of economics at Brown University.

Giorgio Primiceri is a professor of economics at Northwestern University.

Andrea Tambalotti is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Andrea Tambalotti is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Florin Bilbiie, Gauti Eggertsson, Giorgio Primiceri, and Andrea Tambalotti, “’Excess Savings’ Are Not Excessive,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 5, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/04/excess-savings-are-not-excessive.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Two additional considerations for gauging how much consumer spending may increase as the economy reopens are that spending on goods has surged above prior trends as households have been spending more time at home and that there is substitution between goods and services in many cases, i.e. restaurant meals and food at home. This will limit the surge in consumer spending even as spending on services recovers.