Today’s release of the New York Fed’s Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit for the first quarter of 2015 reports a flattening in household debt balances. The slow growth in debt balances has left many wondering about the dynamics behind this change—who is borrowing, and who is paying down their balances? Thus, we use the same data set, the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel (which is itself based on Equifax credit data) to identify the changes in balances by credit score, updating a post from last year with more recent data and also providing an in-depth look at the change in mortgage balances.

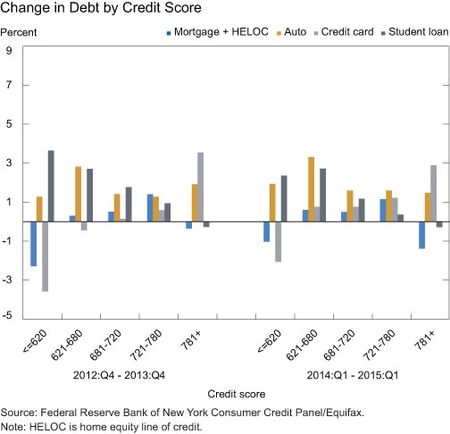

The charts below show contributions to changes in debt balances by borrowers’ credit scores (Equifax Riskscores), first looking at the data we presented in our earlier post (2012:Q4 to 2013:Q4) and then the most recent data, from 2014:Q1 to 2015:Q1. Since the figures are expressed as growth contributions, summing the numbers for a given loan type produces the overall percentage growth for that type over the relevant four-quarter period. The changes in contributions since 2013 are relatively modest, but there have been some important developments. The first notable difference is that credit card balances rose more democratically this time—with borrowers with credit scores over 620 all contributing to the increased balance. And there’s one difference that stands out even more, which is that the most creditworthy borrowers held back housing debt growth even more significantly during the most recent four-quarter period.

Since mortgages are the largest form of debt held by households, their slow growth has an outsized effect on the growth of the total balance. Accordingly, we dig a bit deeper to find out what’s been happening to mortgage balances. The first thing to note is that declining balances at the bottom of the credit score distribution are largely associated with charge-offs from completed foreclosures. So at the top of the credit score distribution, the decline in balances must be driven by something else. One factor that could cause balances to fall in this way would be downsizing by older households (who tend to have the highest credit scores). But why would downsizing suddenly accelerate in the last year?

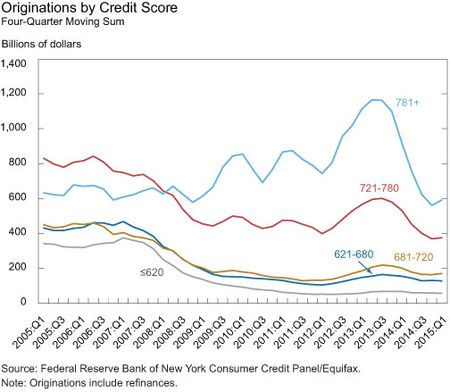

To get a clearer picture, we show (below) a four-quarter moving sum of mortgage originations, including refinances, broken out by credit score.

This chart shows several important things. First, new mortgage origination has really dropped off since 2013. At its peak in mid-2013, mortgage originations were running roughly 70 percent higher than their current levels.

Second, borrowers with credit scores below 620 (or even below 680) have contributed relatively little to originations since the beginning of the housing bust. It’s easy to see that since 2008, the lion’s share of originations have gone to borrowers with credit scores above 720.

Third, even relatively high levels of originations aren’t necessarily associated with rising balances. The upsurge in originations by creditworthy borrowers in 2012 and 2013 consisted mostly of refinances and added relatively little to outstanding balances, thanks to record-low mortgage rates. In fact, that surge in originations a couple of years ago may turn out to be an important source of the reductions in balances by high credit score borrowers that we have observed over the last year.

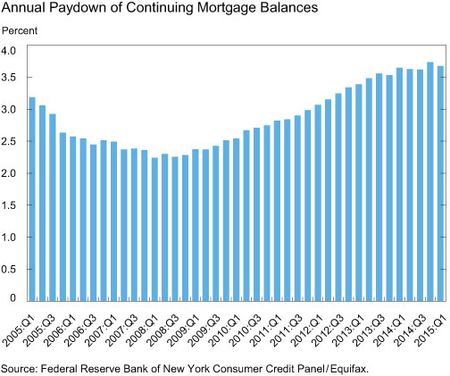

Our final chart shows the amount of balance paydowns that resulted from borrowers making scheduled payments on their mortgages. The key fact is that in the wake of the 2013 re-financing boom for high credit score borrowers, the paydown for those groups, and thus in the aggregate, accelerated. We don’t know yet exactly what caused this change, but both lower interest rates and shorter mortgage maturities would cause the principal share of payments to rise, so a combination of these phenomena could be partially responsible for the slow growth in mortgage balances. We will continue to monitor these trends closely.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Andrew Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is a research officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is the administrator of the Center for Microeconomic Data in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics