Tanju Yorulmazer

This post is the ninth in a series of thirteen Liberty Street Economics posts on Large and Complex Banks. For more on this topic, see this special issue of the Economic Policy Review.

During the recent crisis, some of the largest and most prominent financial institutions failed or nearly failed, requiring extraordinary intervention from regulators, such as extended access to lender-of-last-resort facilities, debt and deposit guarantees, and injection of capital to mitigate systemic risk. Banks and other financial intermediaries perform important functions, such as channeling resources from savers to productive projects and providing payment services to customers through their money-like liabilities. Hence, their failure can disrupt the economy, and an efficient resolution mechanism can mitigate those disruptions. In our contribution to the Economic Policy Review volume, Phoebe White and I develop a simple framework to analyze resolution of failed banks. First, we discuss the costs associated with the failure and resolution of banks. Then, we review resolution policies used by authorities and analyze the optimality of resolution options. Our main message is that the optimality and the feasibility of resolution options depend not only on the characteristics of the failed bank itself, but also on the health of the entire banking system, which warrants a macroprudential approach.

Costs of Bank Failures

In the United States, two common forms of bankruptcy are Chapter 7 liquidation and Chapter 11 reorganization. In Chapter 7 liquidation, the firm is taken over by a receiver that liquidates the assets and distributes the proceeds to the creditors. Alternatively, in Chapter 11 reorganization, the firm is reorganized under a trustee. Resolving a failed bank through general insolvency proceedings is difficult for a number of reasons. First, banks are characterized by significant financial fragility due to their maturity-liquidity mismatch; they issue liquid, short-term liabilities but hold illiquid, long-term assets. As banks perform essential roles in the functioning of financial markets and the economy, their failure can have considerable costs and externalities. Thus, prompt action, as opposed to the lengthy bankruptcy process, is important for resolving banks expeditiously while maintaining public confidence.

Broadly, we put the costs associated with bank failures into four categories:

Disruptions to the failed bank’s customers: Banks channel funds from savers to investors. Investors that use bank financing and have an established relationship with their bank may find it difficult to find alternative sources of finance when their bank fails. On the liability side, banks have liquid liabilities that can act as money. Hence, a bank’s failure can disrupt payment services for its customers.

Contagion: The failure of a bank can have adverse effects on others through various channels, such as i) banks’ direct exposures to the failed bank; ii) information contagion, where creditors of other banks perceive the failure as a negative signal about their own bank, which can create “wrong runs” (where even healthy banks fail); and iii) fire-sale externalities, where the sale of assets of the failed bank can depress the value of the assets of others, thereby possibly triggering further sales that lead to a fire-sale spiral.

Fiscal costs: Resolution of failed banks is usually associated with fiscal costs that can arise from payments through the deposit insurance fund when the fund has been exhausted, from recapitalization of distressed banks, and from administrative costs associated with restructuring and the liquidation of the failed bank. These costs are exacerbated when governments need to intervene and come up with funds quickly; that is, immediacy can entail further costs.

Incentives: During systemic crises, regulators may feel compelled to provide assistance. This may create incentives for banks to take excessive risk (moral hazard). Hence, during any regulatory intervention the potential costs of moral hazard should also be taken into account.

Resolution Methods

Here, we provide a brief description of the methods widely used by authorities to resolve banks. (Table 3 in our paper provides a summary of resolution options and the relative costs associated with each resolution option.)

Mergers and acquisitions: The bank can be acquired by another healthy bank since it may still be an attractive target for other banks due to its franchise value. This is a private sector resolution that doesn’t require any public sector intervention or administration.

Purchase and assumption (P&A): The failing institution enters receivership and its charter is terminated. In a P&A transaction, all or part of the assets and liabilities are transferred to another institution. While P&A is still a private sector resolution, it may require the use of some public funds as in an assisted P&A, where authorities can provide guarantees, including loss-sharing agreements.

Bridge bank: A new bank, so called “bridge bank,” is set up in order to maintain banking operations until a permanent solution can be implemented. Typically, only a portion of the assets would be transferred to the bridge bank while the remaining assets would be liquidated. The bridge bank is ultimately designed to be sold through a P&A transaction.

Good-bank/bad-bank separation: The bank in distress is split in two: a “good bank,” which retains the performing assets, and a “bad bank,” which receives the remaining assets that would be restructured or liquidated.

Liquidation and deposit payoff: In liquidation, the institution is closed and the assets are placed in a liquidating receivership. The liquidation value of the assets is used to repay creditors.

Recapitalization: The institution is kept open through public assistance. This can be done in a number of ways, ranging from a restructuring, or “bail-in” that forces creditors to write off some of their claims, to a nationalization, in which shareholders are wiped out and management is replaced, to a capital injection, in which shareholders are diluted but remain and management doesn’t change.

Feasibility and Tradeoffs

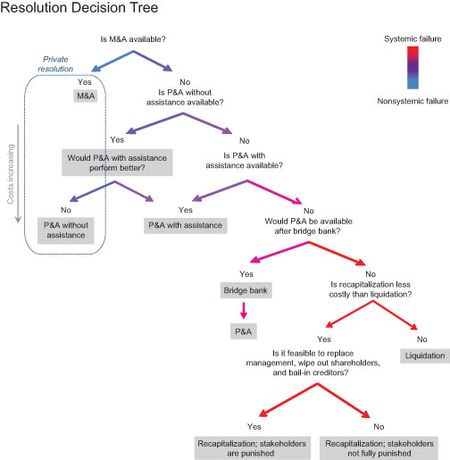

So far, we’ve discussed the costs associated with the failure and resolution of banks and the methods authorities use to resolve failed banks. The aforementioned table summarizes the resolution options and their relative costs. If available, a private sector resolution, through which the failed bank is acquired by a healthy bank, imposes the least costs, since the franchise value is preserved; there’s no disruption to the bank’s customers or the payment system itself, and there are no fiscal costs. The feasibility of such an option depends on the availability of a healthy bank ready to acquire the failed bank. This depends on the characteristics of the failed bank, such as losses incurred by the failed bank and the size and complexity of the failed bank, as well as the health of potential acquirers. In a systemic crisis, where many banks experience distress at the same time, a failed bank that could’ve been easily sold in normal times may not have healthy ready buyers to acquire it. When a private sector resolution isn’t feasible, the authorities must resort to assisted sales, liquidation, and recapitalization—each of which entails certain tradeoffs and costs; the diagram below provides a “decision tree” for the resolution of failed banks that summarizes our main point. Hence, resolution during systemic crises is associated with tradeoffs in terms of costs. Further, it requires a macroprudential view of the entire financial system, rather than a microprudential view of only the failed bank’s characteristics.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Tanju Yorulmazer is a research officer at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics