Rajashri Chakrabarti, Amy Farber, and Max Livingston

In two recent posts on New York and New Jersey and a series of interactive graphics, we explored the effect of the Great Recession on school district finances. But if we expand our scope a little wider, we see that school finances have been changing significantly over the past century. This makes sense, as schools have also changed a lot. Although we may take our current system for granted, schools at the turn of the century looked rather different from their present-day counterparts. As ideas of how to educate students changed, and as education became more common in the population, momentous changes took place not only in how education is imparted, but also in how much education costs and how it’s funded.

While the general format of education—a teacher standing in front of a class of students—has stayed pretty constant over the past century, almost everything about that interaction has changed. The one-room schoolhouse was once standard; now, students are generally split into smaller and more focused classes.

In the one-room schoolhouse, there was just one teacher responsible for educating all the students; now, we have more professionalized and specialized teachers, aides, counselors, coaches, and paraprofessionals. If students lived far away from school, there were no buses to transport them. So while we can look at a picture from the early twentieth century and identify it as a school, it looks incredibly antiquated compared with our current idea of what a school is.

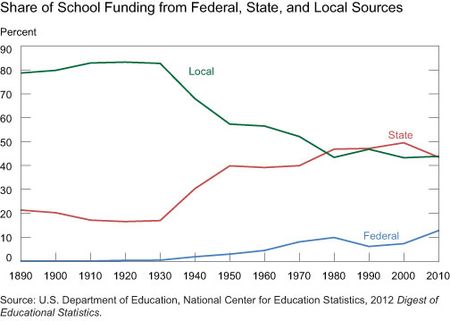

One of the key findings of our analysis of the Great Recession was that the role of the federal government increased dramatically due to the stimulus. But for most of our nation’s history, the federal government played absolutely no role in funding elementary and secondary education. Until around 1930, the funding of education was clearly the responsibility of local governments, with some contribution from the state. In the latter half of the twentieth century, the split between state and local funding changed from around 80-20 to 45-45, with the federal government now paying the remaining 10 percent.

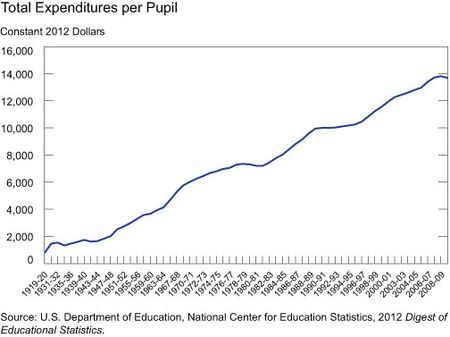

The other striking trend in the historical data is the steady increase in education spending. In 1920, approximately $760 (adjusted for inflation) was spent per student. That number doubled between 1920 and 1930 to approximately $1,500.

During the Great Depression, per-pupil expenditures remained flat or declined slightly. However, since the end of World War II, expenditures have been increasing, peaking at almost $14,000 per student in 2009. The next year, 2010, was the first to see an overall decline in per-pupil expenditures in nearly three decades, likely caused by the aftereffects of the Great Recession. One reason for the dramatic increase during the late twentieth century is the shift from one-room schoolhouses to smaller classes, which require more teachers.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Amy Farber is a research librarian in the Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics