Hamid Mehran and Stavros Peristiani

In global finance, leveraged buyouts (LBOs) are an important tool for restructuring corporations. LBO activities have had a turbulent history in the United States over the last three decades—from the junk-bond-financed wave of the 1980s to the most recent boom-and-bust episode of 2006-07 caused by the collapse of asset-backed securitization. The stylized view is that buyouts are a tool for extracting value through reorganization by streamlining low-growth public firms that have stable cash flows. This post shows that younger public firms experiencing weak financial interest from security analysts and low investor recognition are also more likely to go private. In many cases, founders and managers of these firms with insufficient analyst following had the opportunity to ascertain firsthand the costs and benefits of both private and public ownership, and they decided to go private again.

A Brief History of U.S. Leveraged Buyouts

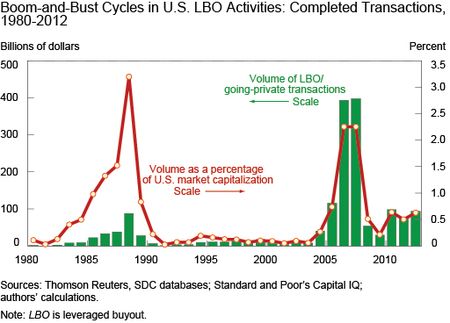

The dramatic surge in LBO activities in the 1980s was made possible by the emergence of the high-yield bond market as the dominant source of financing for speculative-grade debt (see the chart below). While default was very rare among LBO firms in the early 1980s, by the end of the decade, excess speculation and overpriced deals became quite pervasive. Following several high-profile corporate bankruptcies, the junk bond market imploded in 1989. After the collapse of the junk bond market, interest in LBOs cooled off considerably in the 1990s. Facing new, more stringent risk-weighted capital requirement rules and more intense regulatory scrutiny, commercial banks also contributed to the declining interest in buyouts by refusing to finance deals.

The resurgence in the volume of LBO deals in the mid-2000s was spurred by the growing pool of private equity firms that raised capital from large institutional investors. The emergence of asset-backed securitization also radically changed the funding of LBOs as the buyout market transitioned from high-yield bond financing to financing conducted largely through syndicated leveraged loans. At the peak of the LBO market in 2007, collateralized loan obligation securities provided close to two-thirds of the funding for the institutional loan issuance.

Despite the collapse of the asset securitization market, buyout activities have slowly reemerged over the last few years. In many ways, the LBO market has performed considerably better in the years following the recent financial crisis than it did in the wake of previous downturns. For example, the collapse of the junk bond market in the late 1980s was more onerous for LBO sponsors that struggled to find alternative sources of financing for many years.

The Profile of LBO Targets

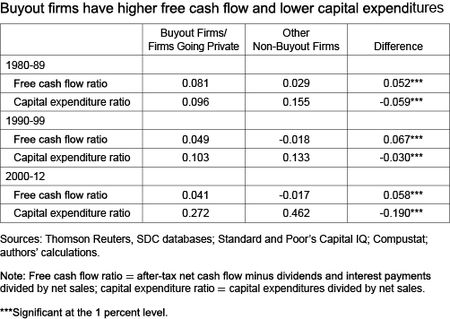

LBOs are a mechanism for disciplining inefficient corporate organizations and realigning the interests of stockholders and management. Agency problems—that is, conflicts of interest between stockholders and management—are more prevalent in low-growth stable firms with substantial free cash flows. Managers of these firms are more likely to squander these cash flows on unprofitable investment projects. LBOs mitigate these agency conflicts by enabling managers to own a larger stake in the firm and enhance managerial discipline through the high debt service imposed on the firms. The downside of greater leverage, however, is that it also raises default risks for debt-laden buyout targets that become more vulnerable to economic downturns and industry-specific shocks. The importance of these firm features is seen in the table below, which shows that buyout targets generated significantly greater free cash flow and had lower investment spending than did their non-LBO peers over the last three decades.

Starting in the 1990s, the corporate sector experienced more proactive monitoring by institutional investors. Managerial compensation was increasingly tied to performance as a significant portion of a chief executive officer’s pay was awarded in stock. All these improvements in corporate governance should have lessened the need for buyout discipline. Thus, the resurgence of LBOs in the 2000s suggests that these transactions might also be motivated by several other factors—for example, the desire to avoid regulatory costs and shareholder scrutiny, or the use of debt financing to lower tax obligations.

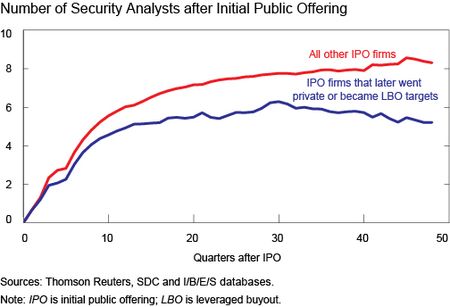

In a recent paper in the New York Fed’s Staff Reports series, we document that many of the companies electing to go private did so only about five years after they went public for the first time. We find that the desire among these relatively young firms to go private is attributable to their inability to attract sufficient financial visibility, measured by analyst coverage (see the chart below). One of the potential benefits of going public is that these firms would be more closely monitored by security analysts that collect and disseminate valuable information to investors.

Financial visibility is very important for younger, less known public companies. Greater financial visibility can enhance stock liquidity, boost firm value, and lower financing costs. Firms that go public strive to reach an optimal scale of financial recognition to compensate for the costs of public ownership. Our staff report shows that firms that do not fully realize the benefits of their public listing are more inclined to go private.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Hamid Mehran is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Hamid Mehran is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Stavros Peristiani is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

Stavros Peristiani is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics