Jonathan McCarthy

This post updates and extends my

July 2011 blog piece on household discretionary

services expenditures. I examine the most recent data to see what they reveal about

the depth of decline in expenditures in the last recession and the extent of

the recovery, and find that the expenditures appear to be further below the peak

identified earlier. I then compare the pace of recovery for discretionary and

nondiscretionary services in this expansion with that of previous expansions,

finding that the pace in both cases is well below that of previous cycles. In

summary, household spending continues to be constrained by a combination of

credit conditions and weak income expectations.

Depth of Decline

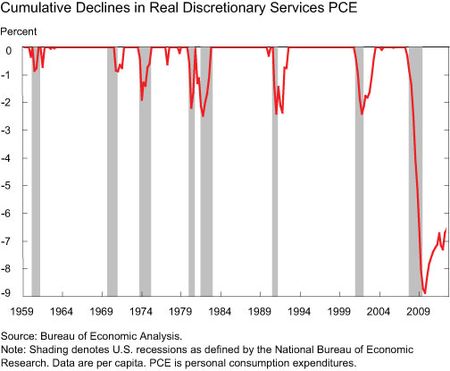

The chart below updates a similar chart from my previous post showing the

extent of the decline in real per capita discretionary services expenditures

from the previous peak. (A zero value in this chart and the following chart

indicates that expenditures were above their previous peak.) The differences

between this chart and the prior one result from two factors: the release of

data for additional quarters; and the revisions of previously released data.

When we compare this chart with the companion

chart in the prior post, a couple of points are evident. First, the decline in

expenditures was much more severe in the 2007-09 recession than in the 2001 downturn;

moreover, the maximum decline of nearly 9 percent is considerably greater than

the estimated maximum decline using the data from early July 2011. Second, five

years after their peak, expenditures are still about 6.5 percent down (which is roughly similar

to the estimate of the maximum decline reported in my previous post).

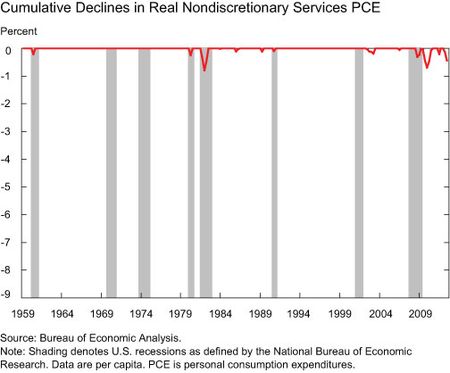

Offering another comparison, the

next chart presents the decline from the previous peak for the other portion of

services expenditures, which I label “nondiscretionary” services expenditures. (See

my prior post

for a definition of discretionary versus nondiscretionary expenditures.) As

seen in the chart, the fall in these expenditures in the past recession was

much less than the drop in discretionary services. In addition, while the

maximum decline in nondiscretionary services expenditures is large compared with

previous declines, it’s not unprecedentedly large, and these expenditures are above their prerecession levels, even though they have declined modestly in the second and third quarters of this year. These patterns indicate that, consistent with

the notions behind these labels, households responded to the severe income

declines of the recession by cutting back on spending on discretionary services

and by trying to maintain spending on nondiscretionary services.

Pace of Recovery

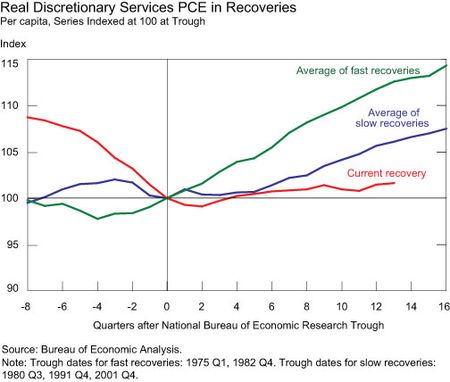

I now examine the pace of recovery for discretionary services spending so

far in this expansion. To do so, I again update a chart from my prior post (showing

an index of real per capita discretionary services expenditures that equals 100

in the quarter at the end of a recession), which allows for a comparison of

this recovery with “fast” recoveries (the average of those following the

1973-75 and 1981-82 recessions) and “slow” recoveries (the average of those

following the 1980, 1990-91, and 2001 recessions). The chart below reveals that

the pace of recovery in the current cycle is still well behind that of previous

cycles. As of 2012:Q3, more than three years after the end of the last recession, discretionary

expenditures were only 1.6 percent above their level at the recession’s trough

(and there has been little change over the past year). In contrast, at this

point in the average slow recovery, these expenditures were 6.1 percent above

the level at the recessions’ trough; in the average fast recovery, they were 12.6 percent above their low point—and were also displaying

steady, solid increases at this stage of the cycle.

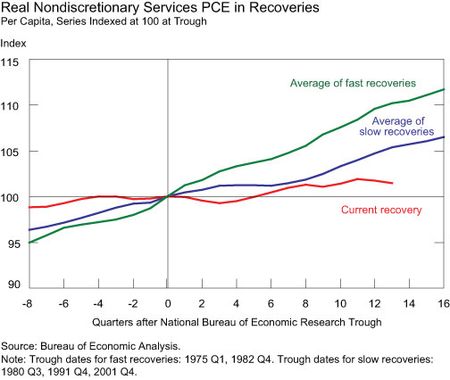

Performing a similar exercise for nondiscretionary

services, I show that these expenditures also have been sluggish in this

expansion relative to previous expansions, even though they didn’t fall that

much during the last recession (see chart below). The level of these

expenditures in 2012:Q3 was 1.5 percent above the level at the last recession’s

trough, compared with 5.4 percent for the average slow recovery and 10.2 percent

for the average fast recovery at the same stage of the cycle.

Conclusion

The pattern of a similarly sluggish pace of recovery for discretionary and

nondiscretionary services expenditures suggests that the fundamentals for

consumer spending remain soft. In particular, it appears that households—more than three

years after the end of the recession—remain wary about their future income

growth and employment prospects even though consumer confidence measures have improved in recent months. In addition, households may still see the need

to repair their balance sheets from the damage incurred during the recession,

especially if they expect that increases in asset prices will be subdued at

best and that credit will continue to be constrained. Consequently, a positive

resolution of these issues is likely necessary before a stronger services and

overall consumer spending recovery can be sustained.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jonathan

McCarthy is a vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the

Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Have you ever thought about the impact of slower population growth and aging on the demand for both discretionary and non discretionary services. It can’t all be income, debt, and sentiment as you will find a much stronger rebound for very discretionary durable and nondurable goods.