Matthew Higgins and Thomas

Klitgaard

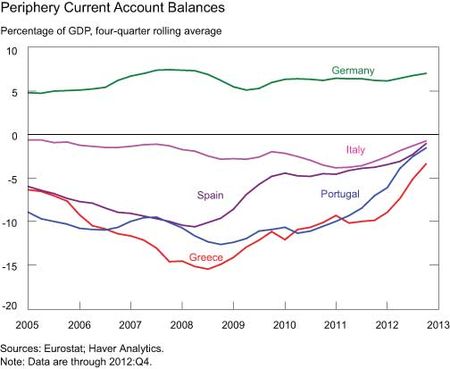

Current account

deficits in euro area periphery countries have now largely disappeared. This

represents a substantial adjustment. Only two years ago, deficits stood at nearly

10 percent of GDP in Greece and Portugal and 5 percent in Spain and Italy (see

chart below). This sharp narrowing means that spending has been brought in line

with income, largely righting an imbalance that had left these countries

dependent on heavy foreign borrowing. However, adjustment has come at a sizable

cost to growth, with lower domestic spending only partly offset by higher

export sales. Downward pressure on domestic spending should abate now that the

periphery countries have been weaned from foreign borrowing. The risk, though,

is that foreign creditors might demand that the countries pay down (rather than

merely service) accumulated external debts, forcing them to reduce spending

below incomes.

A country’s current account balance

measures how much it lends to or borrows from the rest of the world. A country where

imports run ahead of exports is also spending more than it produces and must

borrow abroad to make up the difference. Countries in the euro area periphery borrowed

heavily from abroad during the several years leading up to the ongoing sovereign

debt and banking crisis. As a result, they faced wrenching adjustment pressures

when foreign investors became unwilling to extend new credit, even with the

lure of sharply higher interest rates. These adjustment pressures forced

changes in the balance between exports and imports, and equivalently in the balance

between income and spending, without any help from an exchange rate channel because

of the shared euro currency.

Exports and Imports

The loss in access to foreign credit meant that export revenues had to rise

relative to import purchases. As seen in the table below, much of the recent

adjustment in Italy, Spain, and Portugal has come from higher export revenues. From

2010 to 2012, nominal goods and services exports in these countries rose by 15 percent or more, roughly in line with Germany’s performance. Higher exports in

these countries have helped support growth, softening ongoing economic

downturns. Greece, in contrast, saw export sales rise only 8 percent over this two-year

period; this increase provided only limited help easing the country’s severe

downturn.

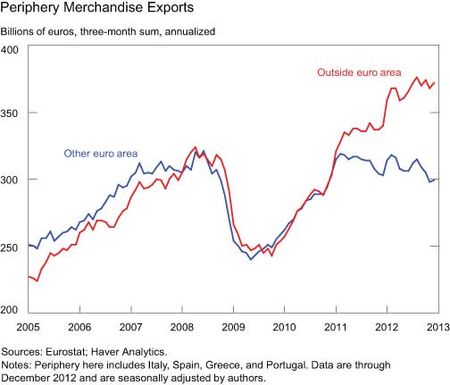

A look at the geographic breakdown of

goods exports shows that the lion’s share of the increase was from sales

outside the euro area, particularly to markets in North America, Asia, and

oil-exporting countries. Indeed, periphery countries’ sales outside the euro area rose by roughly 30 percent over the two-year period, compared with growth of less than 10 percent for sales inside the euro area.

Discussions of external adjustment

in the periphery often stress the need to improve external competitiveness. Unfortunately,

competitiveness measures are at best imperfect. A common metric is based on

unit labor costs, that is, on labor compensation growth relative to labor

productivity. The intuition is simple:

Higher wages erode competitiveness unless offset by productivity gains. However,

this measure can be misleading in turbulent times. The shutdown of low-productivity

firms boosts the economy’s average productivity, but does not mean that

competitiveness has improved at surviving firms. Economy-wide unit labor cost

measures can be particularly misleading when downturns are concentrated in

low-productivity sectors such as construction. For example, much of the

measured decline in Spain’s unit labor costs over the past several years owes

to the country’s construction crash.

The Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development calculates a measure of competitiveness based on

export performance adjusted for the strength of trading partners’ economies. If

exports grow more rapidly than trading partners’ total imports do, a country

gains export market share; if exports grow more slowly, a country loses it.

By this metric, Spain and Portugal

have done well in recent years, with exports growing 6 to 8 percent faster than

trading partners’ total imports from 2010 to 2012. (These figures are based on

preliminary estimates from late 2012.) This matches up well with Germany’s performance

of exports, which grew 5 percent faster than trading partners’ total imports. Italian

exports, in contrast, just kept pace with imports in destination markets. Meanwhile,

Greece lost substantial market share, with exports growing 10 percent more

slowly than destination market imports did over the period.

Import weakness also contributed to the

external adjustment in the periphery. This was particularly true in Greece and

Portugal, where purchases of foreign goods and services dropped 11 percent and 4 percent, respectively, from 2010 to 2012. Italy’s imports rose modestly, while

Spain’s rose 6 percent. In all cases, import growth fell far short of export

growth, helping to reduce external borrowing.

Ongoing economic downturns have been

the key driver of import weakness in the periphery. Indeed, import spending

remains well below levels prevailing before the Great Recession; import

spending in Germany, in contrast, has moved well above it pre-recession level. One

concern is that periphery import spending might pick up quite strongly once economies

recover, bringing a new round of large current account deficits. A more positive

take is that the difficult adjustments have brought imports in line with

exports; going forward, the two can grow together without the need for new

borrowing.

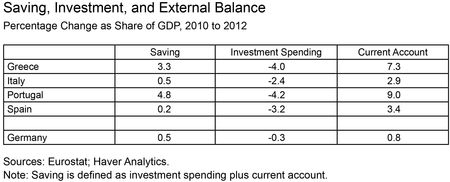

Spending and Income

A current account deficit means that domestic spending is greater than

domestic income. An alternative but equivalent measure of this gap is the

difference between domestic investment and domestic saving. (Note that a

country’s public and private spending goes either to consumption or investment,

while income not spent on current consumption is by definition saved. Thus, the

gap between spending and income is equal to investment spending minus saving. This

same accounting logic means that a country’s fiscal deficit is the difference between

government saving and investment spending.) The table below shows that much of

the narrowing in periphery current account deficits over the past two years has

come from lower investment spending, with declines equal to almost 2 percentage

points of GDP to more than 4 percentage points. Higher saving also contributed

to reduced current account deficits, with small increases in Italy and Spain

and more substantial increases in Greece and Portugal.

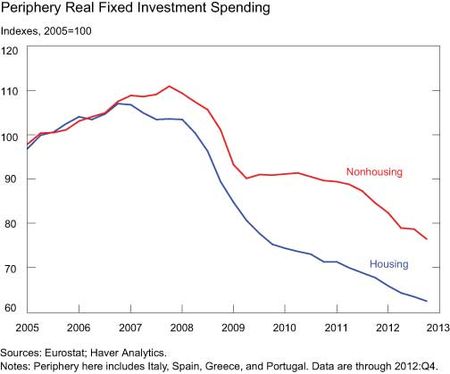

The drop in investment spending,

particularly outside the housing sector, could limit improvement in periphery

competitiveness and growth prospects. As the next chart shows, this is

especially the case since the recent drop in investment comes on the heels of

an already large drop in 2008 and 2009—during the Great Recession but before

the euro area crisis took hold. In contrast, investment spending in Germany has

seen no pullback. Notably, economic recoveries are often led by investment

spending. One risk for the periphery, then, is that stronger growth could see

current account deficits widening as investment spending is again financed by

external borrowing. On the positive side, stronger growth would also help boost

public and private saving by limiting government budget deficits and raising corporate

profits.

Conclusion

Periphery countries have suffered painful

contractions weaning themselves from foreign borrowing. The hope now is that

the restoration of external balance in these countries will set the stage for

meaningful recoveries. The debt burden from past borrowing remains, however, and

argues for caution about the periphery outlook. Much will depend on the

behavior of external investors. A further pullback would force periphery

countries to lower spending below incomes to generate current account surpluses

to pay down (rather than merely service) accumulated external debts. This would

suggest an even steeper drop in periphery consumption and living standards. Recent

balance-of-payments data have been encouraging on that point, however, as

private investors stopped pulling money out of periphery countries in the

second half of 2012, apparently reassured by the European Central Bank’s Outright Monetary Transaction program that was announced last August.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Matthew Higgins is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Emerging Markets and International Affairs Group.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

I believe it always comes down to Germany. Every other single EU country may “adjust” but unless Germany does as well the crisis will never be over. There are always two sides to an equation (and an acc. entity) and we can clearly see the Germans have not done their part during the adjustment process.They should spend more,save less,be tolerant for some inflation and realize that they will share the burden either way. Thank you very much for the article.