The persistence of a gender gap in wages is shaping the debate over women’s equality in the workplace and underscores the challenge facing policymakers as they consider their potential role in closing it. While the disparity affects females at all income levels, women in professional and managerial occupations tend to experience greater gender-pay differences than those in working-class jobs. The rise in the use of incentive pay, which has been linked to the growth of income inequality (Lemieux, MacLeod, and Parent), might have contributed to the gender gap in earnings (Albanesi and Olivetti). In this post, which is based on our related New York Fed staff report, we document three new facts about gender differences in the structure of executive compensation.

Evidence on Gender Differences in Executive Pay

Our research focuses on the top five executives by title in public companies (chair/chief executive officer (CEO), vice chair, president, chief financial officer, and chief operating officer) in Standard and Poor’s ExecuComp database between 1992 and 2005. Only 3.2 percent of people in these roles are women.

Fact 1:

Female executives receive a lower share of incentive pay in total compensation than males. This difference accounts for 93 percent of the unconditional gender gap in total pay.

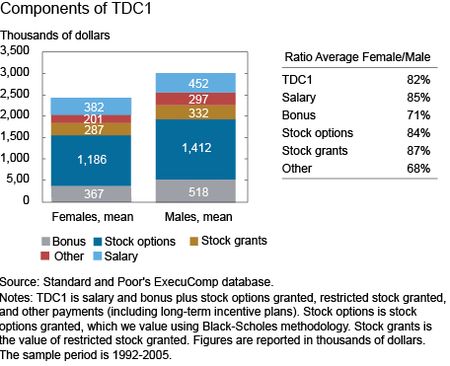

The chart below shows the average components, by gender, of the most common “flow” measure of total compensation (referred to as TDC1), which includes salary as well as an array of incentive pay components linked to firm performance.

We see the biggest gender differences in the compensation components of bonus and other pay, where the female:male ratios are 0.71 and 0.68, respectively. Gender differences in stock options alone account for 41 percent of the disparity in flow compensation. As noted in Fact 1, the cumulative gender gap in incentive pay (the sum of stock options, grants, bonuses, and other pay), accounts for 93 percent of the observed gap in total flow compensation.

Incentive pay leads to the buildup of firm-specific wealth from previous years’ flow of stock options and stock grants. Because small fluctuations in a company’s stock value can lead to large swings in the value of outstanding stock options and stock grants (typically larger than flow components of compensation), we consider two measures of firm-specific wealth stock: the total value of an executive’s accumulated stock options (SOTotal) and total stock grants (SGTotal). The gender differential in the value of stock options (SOTotal) is 75 percent, but the largest gender differential is for stock grants held (SGTotal), 22 percent. Both differentials are significant.

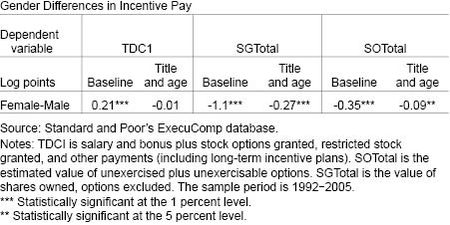

The table below presents the results of regressions of the logarithm of each component of pay on a female indicator dummy, controlling for time and firm fixed effects as a baseline, while also adding title and age. Consistent with earlier studies (Betrand and Hallock), the gender differential in TDC1 disappears with these additional controls, suggesting that women’s younger age and lower representation in CEO positions explains most of the gender gap in flow compensation. However, sizable gender differentials in SGTotal and SOTotal still remain after conditioning on age and title.

Fact 2:

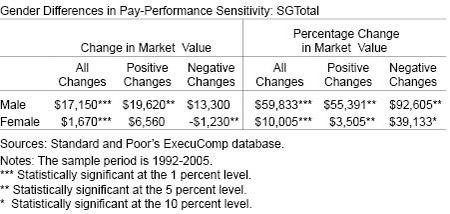

Compensation of female executives is less sensitive to firm performance than males’. For example, a $1 million increase in firm value generates a $17,150 increase in firm-specific wealth for male executives but only a $1,670 increase for females. For each 1 percent increase in firm market value, compensation rises by $60,000 for men and only $10,000 for women.

The next table shows the results of regressions of the change in the executive’s firm-specific wealth on firm performance (in dollars and in percentages), a female dummy, and the female dummy’s interaction with the change in firm value. In all cases, gender differences in pay-performance sensitivity are large and significant.

Fact 3:

Compensation of female executives is more exposed to declines in firm value and less exposed to increases in firm value than males’. We find that a 1 percent rise in firm value is associated with a 13 percent rise in firm-specific wealth for female executives and a 44 percent rise for male executives. Conversely, a 1 percent decline in firm value is associated with a 63 percent decline in firm-specific wealth for female executives and a 33 percent decline for males.

Female executives have on average lower total stock grants (SGTotal). Therefore, fluctuations in pay driven by a given change in firm value correspond to a greater fraction of their average pay, even if male executives exhibit higher sensitivity. Moreover, positive changes in firm value are much more frequent than negative changes. Since the gender differences in sensitivity are smaller for negative changes than for positive ones, this affects the overall relationship between firm performance and pay by gender.

To illustrate this point, we perform a back-of-the-envelope calculation of exposure using estimated pay-performance sensitivity and average changes in firm market value. Female executives are less exposed to positive changes in firm market value and more exposed to negative changes in market value. For example, we find that pay for female executives cumulatively declined by 16 percent as a result of exposure to changes in firm market value, while pay for males rose by 15 percent cumulatively over the sample period.

Although female executives receive lower incentive pay and have lower pay-performance sensitivity, they experience greater exposure to negative changes in firm value and smaller exposure to positive changes in firm value (as a fraction of their average stock grant holdings) compared with male executives. So, overall, changes in firm performance penalize female executives while they favor male executives.

Are these gender differences in compensation efficient?

Surveys of professionals and executives, time-use studies, and experimental and psychological studies suggest that:

- Exclusion from informal networks, gender stereotyping, and lack of role models are perceived as substantial barriers to career advancements for female executives.

- Married female professionals bear a disproportionately large share of childcare responsibilities relative to married men in similar circumstances.

- Women display lower propensity to enter into competitive environments.

- Women display lower propensity to initiate negotiations.

- Women exhibit higher risk aversion.

Based on the efficient paradigm of the pay-setting process, these gender differences in barriers to career advancement and preferences are consistent with Facts 1 and 2, but they would imply lower performance for firms headed by females, an outcome for which we find no evidence in our data. Moreover, this framework cannot explain Fact 3.

We find instead that the gender differences in pay and pay-performance sensitivity are consistent with the “skimming” or “managerial power” view of executive compensation. According to this theory, board members are captive to executives, who use that position to influence their compensation packages in a way that increases their average pay and undermines incentives. In this scenario, the goal of the executive is to prevent pay from falling when firm performance deteriorates and to boost pay when the company is doing well. However, as we document in our paper, top female executives are less entrenched than their male counterparts, since they are usually younger, with fewer years of tenure and weaker networks. Thus, they are more limited than male executives in their ability to control their own compensation.

Our analysis suggests that performance pay schemes should be held to closer scrutiny. Increasing transparency about an executive’s compensation, both in absolute terms and relative to counterparts’, might mitigate gender-pay inequality for top executives. A recent Securities and Exchange Commission ruling that says that companies have to disclose whether executive pay is in line with the company’s financial performance seems to be a good step in this direction.

Our findings also raise concern about the standing of all professional women as incentive pay schemes proliferate outside the executive ranks. The failure of the efficient contracting paradigm to explain the gender differences in the structure of executive compensation points to possible distortions in the link between pay and performance. To the extent that performance pay amplifies earnings differentials resulting from actual or perceived differences in attributes between workers, it can exacerbate inequality and can severely distort the allocation of resources, if designed incorrectly.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Stefania Albanesi is a research officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Claudia Olivetti is a professor of economics at Boston College.

Maria Prados is an associate economist at University of Southern California’s Center for Economic and Social Research.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

As a professional woman with children my experience has been that working woman hesitate to go for the big job or change jobs at all because their need/desire for flexibility in the workplace is so important to them. Many of my friends and colleagues have said they would forego a pay raise for the peace of mind that they can leave when they need to take care of their family or alter their work schedule. Often times this flexibility has been created because they have worked so long at once place and don’t feel they can negotiate this at a new place of work. Many well educated, talented woman feel left out of opportunities to contribute their skills because of their commitment to being present parents in addition to professionals.

I have researched this also. If you plot the salaries of men and women over time it widens at about 28 and then rejoins at about 52. There is a simple reason for this. Women leave the workplace to have and raise children and then rejoin the workforce. It is clear and obvious.