From the fourth quarter of 2017 through the third quarter of 2018, the average contract interest rate on new thirty-year fixed rate mortgages rose by roughly 70 basis points—from 3.9 percent to 4.6 percent. During this same period, there was a broad-based slowing in housing market activity with sales of new single-family homes declining by 7.6 percent while sales of existing single-family homes fell by 4.6 percent. Interestingly though, these declines in home sales were larger than in the two previous episodes when mortgage interest rates rose by a comparable amount. This post considers whether provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) might have also contributed to the recent decline in housing market activity.

A Liberty Street Economics post published last April reviewed in detail the pieces of that legislation relevant for determining the after-tax cost of owning a home. The analysis concluded that homeowners across a wide range of home prices would experience a significant increase in after-tax ownership costs, especially in areas of the United States that have high income and property taxes on the state and local level. This post intends to build on that analysis by providing circumstantial evidence that specific provisions such as a $10,000 cap on the deductibility of state and local taxes, a lower limit on the amount of mortgage debt on which interest is deductible, and lower marginal tax rates have negatively impacted the housing market. (In a follow-up post, our colleagues will provide empirical evidence that reaches this same conclusion. Unfortunately, neither analysis will estimate exactly how much of the recent slowing is due to higher interest rates versus changes in tax law.)

A Close Look at the Decline in New Home Sales

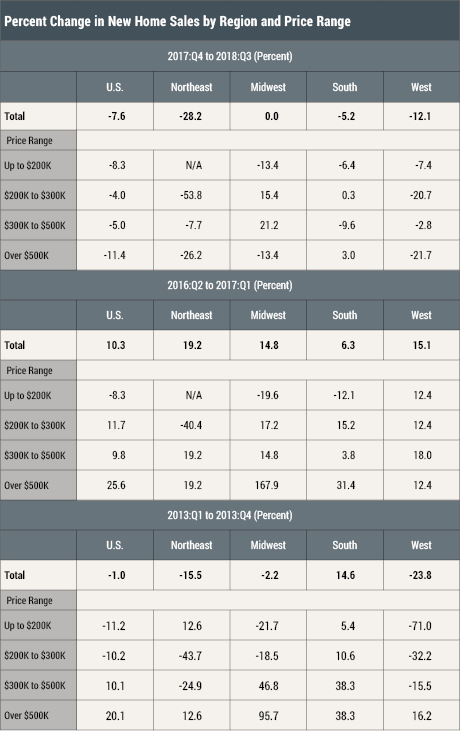

The table below presents information on the decline of new home sales during the period from the fourth quarter of 2017 through the third quarter of 2018 broken out among the four major census regions of the United States and by home price range. We compare this most recent episode with two other relatively recent periods when mortgage interest rates increased by a similar amount: From the second quarter of 2016 through the first quarter of 2017, mortgage rates increased about 60 basis points; from the first quarter of 2013 through the fourth quarter of 2013, mortgage rates rose around 80 basis points.

The first difference to note is that, at the national level, new home sales have fallen significantly over the most recent period. In the period from the first quarter of 2013 through the fourth quarter of 2013, new home sales simply leveled off while the period from the second quarter of 2016 through the first quarter of 2017 actually experienced a 10 percent increase in home sales. Second, in the most recent episode, the largest declines in sales tended to be in the highest price range, which is where homebuyers would be most affected by the tax changes mentioned before. To the extent that sales fell in previous periods, the declines were concentrated in the lower price ranges while the sales in higher price ranges continued to increase.

What is Unique about the Current Episode?

Given the overall strength of the U.S. economy in 2018 as well as the subsequent strong pace of job creation, one might expect the housing market to be able to shrug off the increase in mortgage rates, much like the two previous episodes discussed above. However, this most recent episode is qualitatively different because of changes in the tax code. In what follows we will demonstrate how, in addition to the rise of interest rates, different provisions of the TCJA combine to increase the marginal user cost of capital for homeowners, especially for higher-priced homes and homes in high-tax jurisdictions. We will also consider the role of expected increases in house prices.

One of the fundamental results in housing economics is that the relationship between the price of a home and the cost of renting that home can be defined as Rent=Price * μ, where μ represents the user cost of capital for owner-occupants. A subsequent post from our colleagues will explore the relationship between price and rent further, but our analysis focuses on μ. In the literature, it is widely accepted that the user cost of capital strongly influences demand for owner-occupied housing. Thus, to understand the recent trends in housing, we employ the user cost of capital framework as outlined in Poterba (1984) or Poterba and Sinai (2011), defining the marginal user cost for homeowners who itemize deductions( μI) to be:

where owner-occupants pay mortgage interest at the rate rm on the mortgage balance (LTV = 1 – θ) and property taxes on the value of the property at rate tp. Since those payments can be deducted from gross income for itemizers, their after-tax marginal cost is represented by (1- ty) * ((1 – θ)rm+tp), where ty is the marginal income tax rate. Owner-occupants have to pay the cost of maintenance and depreciation (δ) associated with the property, but benefit from the expected growth in home values (g).

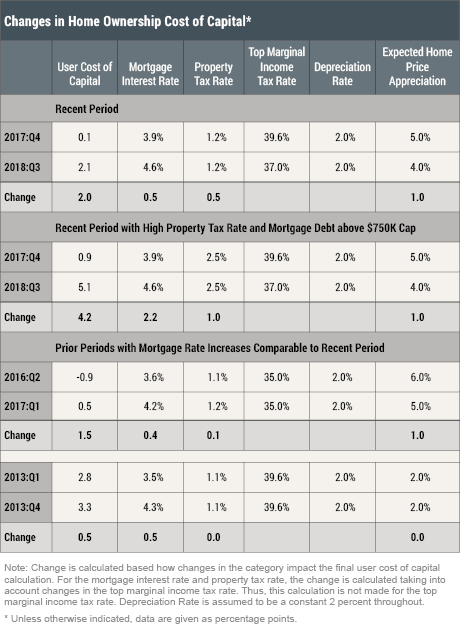

In the table below we estimate the changes in the owners’ user cost of capital that occurred in 2018 using this model, and then compare that amount with the changes during the 2013 and 2016 episodes. It is important to note that these estimates are not exact, but help us to approximate the magnitude and sign of the change in the marginal cost of owning a home across these different time periods.

Looking at the first part of the table labeled “Recent Period,” the relevant variables for calculating the user cost of capital are reported for the fourth quarter of 2017 and the third quarter of 2018. In the fourth quarter of 2017, mortgage interest rates were at a 3.9 percent quarterly average and median property taxes on owner-occupied homes in the United States were 1.2 percent of the homes’ estimated value, according to the American Housing Survey. (The median property tax rate is calculated as the median annual real estate taxes paid as a share of the median home value in the United States according to the American Housing Survey from the U.S. Census Bureau.) Both the mortgage interest and the property taxes were fully deductible with a top marginal income tax rate at 39.6 percent. Thus, we estimate the marginal after-tax cost of mortgage interest and property taxes at 3.1 percent ((1 – ty) * ((1 – θ)rm + tp) = (1 – 0.396) * (0.039 + 0.012) = 3.1 percent).

Next, we add in the estimated annual rate of depreciation for a home of 2 percent, which brings the cost up to 5.1 percent. However, the expected home price appreciation represents a capital gain that offsets some of the cost of ownership and is therefore subtracted from this calculation. Although measuring home price expectations can be challenging, we use the standard practice of assuming prospective home buyers have “adaptive” expectations whereby they align future expectations with the recently realized rates of appreciation in the housing market. For our measure of expected home price appreciation, we use the annualized sixteen-quarter percent change in the Price Index of New 1-Family Houses Sold published by the U.S. Census Bureau to measure the change in price of a “constant quality” new home, including the value of the land that the home sits on.

Using this metric, the expected home price appreciation was 5 percent in the fourth quarter of 2017 measure, which brings the final user cost of capital for the quarter to essentially zero, or 0.1 percent. This calculation is replicated for each quarter with the relevant housing cost variables. Using these calculations, we estimate the total change in the user cost of capital for each period, as well as the contributions to this change from the mortgage interest rate, property tax rate, and expectations for home price appreciation given the marginal income tax rate.

Moving forward to the third quarter of 2018, in addition to the increase of mortgage interest rates, there has been important changes in the tax treatment of homeownership. The top marginal income tax rate fell from 39.6 percent to 37 percent, meaning that the tax savings from itemized deductions fell by 2.6 percentage points. Additionally, we present two cases for the most recent period with different property tax rates. For this case, property taxes are assumed to be at the national median of 1.2 percent of property values so that, at the margin, property taxes are no longer deductible although mortgage interest payments are still deductible. The effect is to raise the effective property tax rate by 0.5 percentage point. Using these assumptions, our analysis estimates that the user cost of capital to owners increases from 0.1 percent to 2.1 percent, and that a major part of this is due to a 1 percentage point decline in our measure of expected home price appreciation.

In the next section we present analysis of the recent period focusing on high-priced homes in areas with higher tax rates. We assume property taxes are 2.5 percent of the home value, which is typical for a high-tax jurisdiction, and that the amount borrowed to purchase the home exceeds the cap of $750,000, which is often the case for homes in higher price ranges. This means that the mortgage interest is no longer deductible at the margin, raising the effective mortgage rate by 2.2 percentage points. Under these assumptions, the cost of capital appears to increase from around 1 percent to 5 percent for these homes.

Comparing either case with the estimated change in the two previous episodes, we see that the most recent period experienced the greatest increase in user cost of capital. From the second quarter of 2016 through the first quarter of 2017, the marginal user cost rose around 1.5 percentage points as the result of higher mortgage rates, a slight increase in the median property tax rate, and lower expectations for home price appreciation. In the first quarter of 2013 through the fourth quarter of 2013 episode, the marginal user cost rose by only 0.5 percentage points because of the increase of mortgage interest rates. For both of these past episodes, the increase in the marginal user cost of capital is less than in the most recent one, particularly under the assumptions for higher-priced homes in high-tax jurisdictions.

Conclusion

While certainly not conclusive, the evidence presented above is consistent with the view that changes in federal tax laws enacted in December of 2017 have contributed to the slowing of housing market activity that occurred over the course of 2018. Specifically, this slowdown stems from a higher user cost of capital caused by lower marginal tax rates, the $10,000 cap on the deductibility of state and local taxes, and the lower limit for the amount of mortgage debt on which interest payments are deductible.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Richard Peach is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Peach is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Casey McQuillan is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Casey McQuillan is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Richard Peach and Casey McQuillan, “Is the Recent Tax Reform Playing a Role in the Decline of Home Sales?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), April 15, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/04/is-the-recent-tax-reform-playing-a-role-in-the-decline-of-home-sales.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thanks for putting together this interesting summary of relative housing price trends and potential drivers of some of these changes. I would like to add a couple of additional considerations to this discussion. First, I believe that the practical effects of the SALT (deduction limitations) may be overestimated due to a factor which has only recently been referenced in the published SALT discussions. Specifically, AMT tax calculations eliminated 100% of my State and Local tax deductions years ago, and well before the recent 10,000 limit which was imposed by the new tax regulations. I believe that this would be true for the majority of high end home buyers. Second, there is another significant cause of declining sales and prices in the higher price spectrum which also happens to be highly correlated with the States which have the highest State and Local taxes and that is the loss of major employers in reaction to the unfavorable local conditions (not only taxes). For example in our State, some of the largest employers such as Aetna and GE have left the state. Similarly, two large International Banks who had moved large operations to Fairfield County years ago, recently decided to return to NYC. The losses of these large employers caused a very significant softening in local real estate conditions and these effects also emerged well before the recent tax law changes.