Workers in the United States experience vast differences in lifetime earnings. Individuals in the 90th percentile earn around seven times more than those in the 10th percentile, and those in the top percentile earn almost twenty times more. A large share of these differences arise over the course of people’s careers. What accounts for these vastly different outcomes in the labor market? Why do some individuals experience much steeper earnings profiles than others? Previous research has shown that the “job ladder”—in which workers obtain large pay increases when they switch to better jobs or when firms want to poach them—is important for wage growth. In this post, we investigate how job ladders differ across workers.

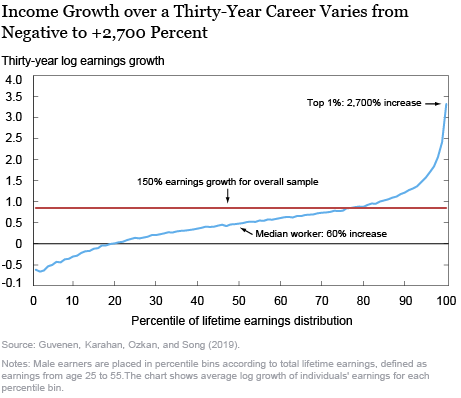

First, to document the disparity in lifetime earnings—defined as total income from wages, salaries, and the labor portion of self-employment income from age 25 to 55—we use data from W-2 forms and self-employment reporting to assess how earnings growth differs among men. (We plan to undertake a similar study in the future that focuses on lifetime earnings of women.) Specifically, we group men into percentiles of total lifetime income and look at how each group’s real average earnings at age 55 compare to their earnings at age 25. The chart below shows that the annual earnings of the median worker increase by about 60 percent. By contrast, workers below the 20th percentile actually experience a decline in earnings, while those in the top 1 percent experience a twenty-seven-fold increase.

To move to better jobs, workers first need to be able to hold on to the ones they have. So one possible explanation for the low earnings growth of low-income individuals is that they do not have access to stable jobs. To investigate this hypothesis, we use data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to rank men by their recent earnings (over the two years prior to the survey date) and group them into five quintiles. The chart below shows that low-income earners indeed face a greater risk of losing their jobs, and by a large margin: Individuals in the bottom quintile are more than three times as likely to become unemployed as those in the top quintile.

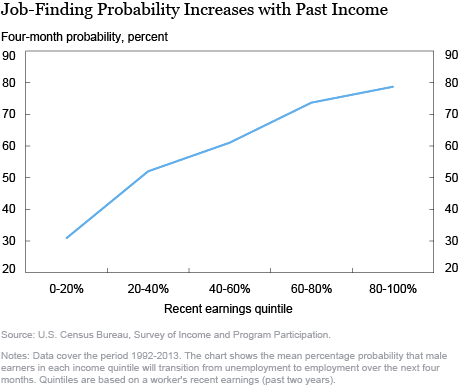

We next turn to job-finding rates. If it takes much longer for low-income individuals to find a job, then the skill loss during unemployment and the stigma employers attach to long-term unemployment can create long-lasting effects on the worker’s subsequent employment and earnings. To check this possibility, we proceed in a fashion similar to our analysis of job stability and compute from SIPP data the job-finding rates of the unemployed in each group (specifically, the fraction of unemployed who have a job after four months). These rates also point to remarkable differences. Nearly 80 percent of the unemployed in the top group are employed again after four months, compared to 31 percent of the lowest earners. Taken together, the two facts imply that low-income earners lose their jobs more frequently and go through longer unemployment spells, underscoring a less stable job ladder.

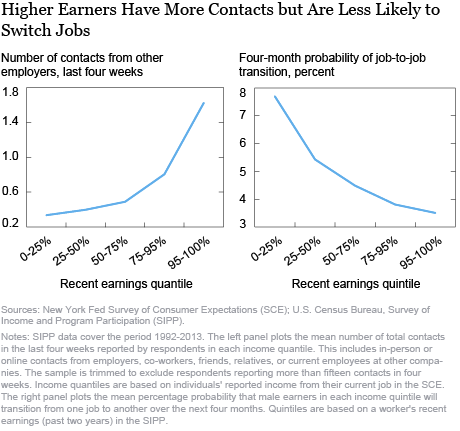

How frequent is job-switching for different income groups? If top earners get more outside offers when employed, they can climb to better jobs faster and enjoy higher wages. Such outside offers can sometimes also lead the employer to raise wages in order to keep the worker. Therefore, we look at two measures. From the Survey of Consumer Expectations, we calculate the number of contacts workers receive about outside options. These include in-person or online contacts from employers, co-workers, friends, relatives, or current employees at other companies. The left panel of the chart below shows that high-income individuals are contacted and asked about alternative opportunities more often than low-income individuals. Indeed, workers in the top 5 percent of earners are contacted at more than twice the rate of earners between the 80th and 95th percentiles.

Do these solicitations lead to job-switching? Not always. Our analysis from SIPP data shows that, even though high earners are solicited more often, these solicitations do not always translate into job-to-job switches (chart below, right panel). In fact, top income earners are much less likely to switch jobs. While we do not know the particular reason for this behavior, it can be the result of either the earner already having a high-paying job or the current employer responding to the risk of losing its worker.

Our analysis concludes that there are large differences in the career trajectory of individuals. Given that those with low incomes have a higher risk of job loss, take longer to find jobs, and have a much lower likelihood of being contacted by better employers, it is no surprise that huge differences in earnings growth arise between low- and high-income workers over a thirty-year period. One interpretation of our findings is that shocks that occur early in a career, such as unemployment, put workers on a trajectory with lower expected wage growth. An alternative interpretation is that while individuals differ in their human capital when they enter the labor market, these differences manifest themselves much later in life through more stable jobs, frequent job-switching, and eventually higher wages. To determine the appropriate policy response to the inequality in lifetime earnings, we need to address the factors that expose some workers to higher unemployment risk and lower chances of getting offers both when unemployed and employed. We leave this important question for future research.

Fatih Karahan is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Brendan Moore is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Brendan Moore is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Serdar Ozkan is an associate professor of economics at the University of Toronto.

How to cite this post:

Fatih Karahan, Brendan Moore, and Serdar Ozkan, “Job Ladders and Careers,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 8, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/10/job-ladders-and-careers.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics