A large volume of financial transactions occur in decentralized markets that commonly depend on a network of dealers. Dealers face two impediments to providing liquidity in these markets. First, dealers may face informed traders. Second, they may face costs associated with maintaining large balance sheets, either due to inventory or liquidity costs. In a recent paper, we study a model of over-the-counter (OTC) markets in which liquidity is endogenously determined by dealers who must contend with both asymmetric information and liquidity costs. This post provides an intuitive explanation of our model and the dynamics of interdealer liquidity.

A Stylized Model of Interdealer Markets

We consider a stylized representation of interdealer markets. First, each dealer makes markets for its clients, who may be interested in buying or selling an asset. Dealers offer a bid-ask spread at which they are willing to execute trades. Next, dealers can trade among themselves. This interdealer market helps dealers manage liquidity. A dealer who purchased an asset from a client would like to sell that asset to rebalance its inventory. Conversely, a dealer who sold an asset to a client will want to purchase the asset in the interdealer market. Dealers have an incentive to trade with each other because they suffer a cost if their inventory is “unbalanced.”

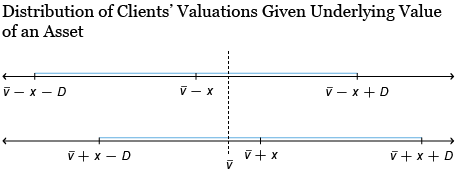

The value of the asset being traded is uncertain to dealers. For simplicity, we assume that the value of the asset can be either high or low. The dealers know the expected value of the asset, but they don’t know the true value. Traders have private asset valuations that are distributed symmetrically around the true value of the asset, which dealers care about. A trader’s private valuation could differ from an asset’s true value—for example, because a trader is liquidity constrained and is desperate to sell the asset to obtain cash.

The next exhibit represents the two possible values of an asset and the distribution of traders’ associated valuations. The top line represents the case where the true value of the asset is low. The traders’ valuations are represented by the blue line, which is centered on the value of the asset. The lower line represents the case where the true value of the asset is high. Again, the traders’ valuations are represented by the blue line. The expected value of the asset is represented by the dotted vertical line.

Acquiring Information through Trade

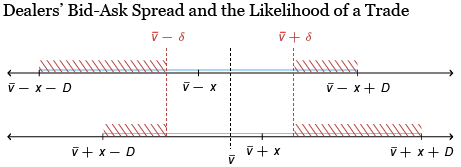

Dealers can learn about the true value of an asset through trading. This is illustrated in the next exhibit, where the bid-ask spread is represented by dashed vertical lines. If a trader values the asset at less than the ask price of the dealer with whom she is matched, she will sell her asset to the dealer. This is represented by the shaded region to the left of the dashed line representing the dealer’s ask price. Conversely, if a trader places a value on the asset that is greater than the bid price of the dealer with whom she is matched, she will purchase the asset from the dealer. This is represented by the shaded region to the right of the dashed line representing the dealer’s bid price.

As can be seen from the exhibit above, a dealer is more likely to sell his asset when the value of the asset is low and buy the asset when the value of the asset is high. Hence, conditional on trading, the dealer gains some information on the true value of the asset.

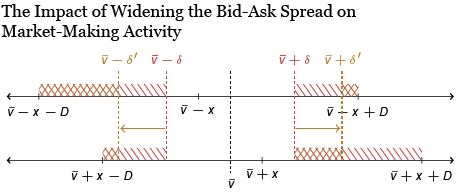

What happens if a dealer chooses a wider bid-ask spread? The exhibit below shows that the dealer learns more about the true value of the asset, conditional on a trade. Indeed, if the dealer sells the asset, for example, it is now much more likely that the true value of the asset is low. This can be seen by the fact that the shaded area to the left of the ask price when the value of the asset is low is much greater than the shaded area to the left of the ask price when the value of the asset is high.

It is possible for a dealer to widen a bid-ask spread to the point that no trader would ever be willing to buy an asset, if its value is low, and no trader would ever be willing to sell an asset, if its value is high. In this extreme case, the dealer would learn the true value of the asset, conditional on trading. It is important to also note that with a wider bid-ask spread, the dealer is less likely to trade. This can be seen by the fact that the shaded areas become smaller as the bid-ask spread widens.

How Is Interdealer Market Liquidity Determined?

Any information acquired by dealers at the market-making stage is useful when dealers expect to trade in the interdealer market. A dealer who is better informed about the true value of an asset could, for example, reject an offer from another dealer if it’s not attractive enough, even though the dealer would have accepted the offer absent the additional information.

At the same time, the informational advantage that a dealer can achieve through its market-making activities diminishes interdealer liquidity. This is because interdealer liquidity is greatest when more dealers with offsetting positions trade. When the bid-ask spread is wider, fewer dealers trade in the market-making stage, reducing trading opportunities in the interdealer market. Fundamentally, there is a conflict between private incentives to obtain an informational edge and the socially efficient provision of liquidity in the market-making stage.

Endogenous Interdealer Trades and Fragility

A key insight from our model is that interdealer liquidity depends on dealers’ market-making activities. Tighter bid-ask spreads, which correspond to greater liquidity provided by dealers to their clients as they make markets, lead to more liquidity in the interdealer market. Wider bid-ask spreads have the opposite effect, reducing liquidity in both markets.

In the extreme case that dealers expect no interdealer trades to occur, their optimal response is to exploit their market power over their customers and offer them wide bid-ask spreads. When that happens, markets become segmented, with dealers making markets for their local markets but not engaging in interdealer trades to offset imbalances between local markets. In other words, illiquidity begets illiquidity.

This problem of expectations substantiating and rationalizing a breakdown in coordination is a form of financial fragility, reminiscent of runs in the context of banking or wholesale money markets. In particular, we show that, under certain circumstances, dealers’ beliefs are an important determinant of interdealer liquidity. For intermediate levels of fundamental uncertainty, dealers’ expectations about other dealers’ market-making practices can rationalize either active interdealer trading or no trading at all. Because spreads dramatically widen in the event of a cessation of interdealer trading, markets could quickly dry up if dealers’ beliefs change abruptly. For example, interdealer trading, which accounts for 61 percent of all trades in sterling OTC markets, fell to 2 percent during the sterling flash crash in October 2016. In a report on the episode, the Financial Conduct Authority cited the sharp withdrawal of dealers from interdealer markets as one of the key catalysts of the crash.

Post-Trade Information Acquisition

If dealers can learn something about the true value of an asset through trading, then they can gather a lot more information by observing many trades. Hypothetically, observing all trades by dealers would reveal the true value of the asset with perfect accuracy. In many financial markets, post-trade processing entities that perform clearing and settlement are naturally positioned to acquire information about executed trades. Trade reporting engines, such as TRACE, are another mechanism through which information about trades can be shared with market participants.

What happens when all dealers know that they will be informed of the true value of the asset before they enter the interdealer market? We find that liquidity improves because dealers no longer have an incentive to learn about the true value of the asset by widening the bid-ask spread. As a result, all dealers set tighter bid-ask spreads, so more trades take place. Since there are more trading opportunities in the interdealer market, it is also easier for dealers to rebalance their inventories and they don’t have to worry about being less informed or being taken advantage of in that market.

When all dealers can become informed, they have fewer incentives to acquire information by setting wide bid-ask spreads, improving liquidity. However, given substantial heterogeneity between dealers, and the profit-maximizing objectives of platforms and exchanges, it is unclear whether rules and practices regarding disclosure will be implemented consistently and effectively. We will explore this issue in a future blog post.

Michael Lee is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Antoine Martin is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Michael Lee and Antoine Martin, “How Does Information Affect Liquidity in Over-the-Counter Markets?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, January 13, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/01/how-does-information-affect-liquidity-in-over-the-counter-markets.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics