The COVID-19 outbreak has triggered unusually fast outflows of dollar funding from emerging market economies (EMEs). These outflows are known as “sudden stop” episodes, and they are typically followed by economic contractions. In this post, we assess the macroeconomic effects of the COVID-induced sudden stop of capital flows to EMEs, using our open-economy DSGE model. Unlike existing frameworks, such as the Federal Reserve Board’s SIGMA model, our model features both domestic and international financial constraints, making it well-suited to capture the effects of an outflow of dollar funding. The model predicts output losses in EMEs due in part to the adverse effect of local currency depreciation on private-sector balance sheets with dollar debts. The financial stresses in EMEs, in turn, spill back to the U.S. economy, through both trade and financial channels. The model-predicted output losses are persistent (consistent with previous sudden stop episodes), with financial effects being a significant drag on the recovery. We stress that we are only tracing out the effects of one particular channel (the stop of capital flows and its associated effect on funding costs) and not the totality of COVID-related effects.

The Macroeconomic Effects of the Sudden Stop on EMEs Can Be Sizable

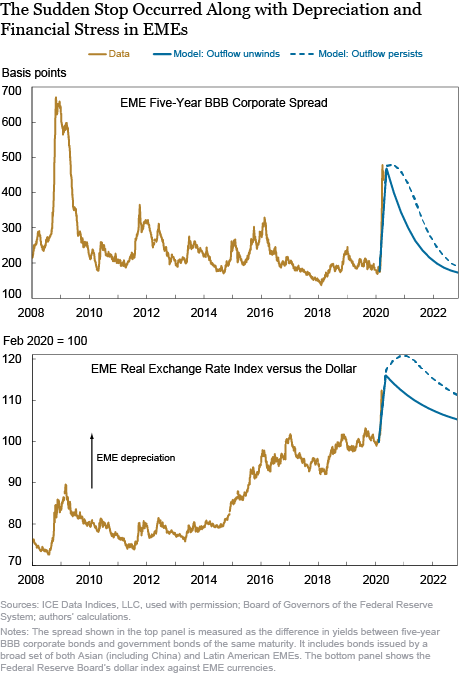

The chart below shows the evolution of EME credit spreads and exchange rates against the dollar since 2008. Credit spreads tightened and the exchange rate depreciated at an unprecedented speed in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States: spreads rose 300 basis points and EME currencies fell 15 percent in just a few weeks since late February.

In the model, we capture the sudden stop to capital flows through a sharp tightening of the international credit constraint, which impairs EME borrowers’ ability to roll over their short-term dollar debt. We size the shock so that the model matches the rise in credit spreads seen since February. The exchange rate depreciation against the dollar predicted by the model roughly matches what has occurred so far.

We consider two scenarios for the evolution of the capital outflow pressure in the coming months, capturing different assumptions about the possible evolution of COVID-19-related risk aversion of global investors. In the first, the outflow pressure simply unwinds from its recent peak, at a rate chosen to replicate the historical persistence in the spread series. In the second, capital outflow pressures persist for a year before easing.

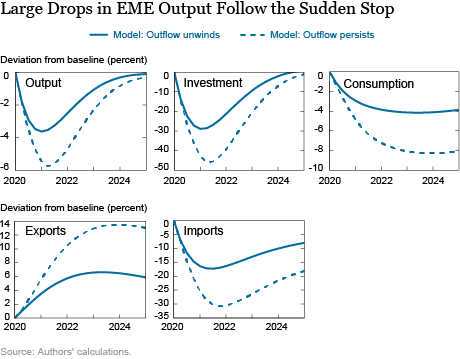

The effects on EMEs of the sudden stop shock are shown in the chart below. As borrowing constraints tighten and currencies depreciate, the balance sheets of EME borrowers deteriorate as firms struggle with their dollar-denominated debt. This deterioration leads to a sharp rise in the cost of capital, depressing investment spending. Because exporting firms set prices in dollars, the boost to exports from currency depreciation is relatively weak: exports rise very little in 2020 and 2021 (see also research documenting evidence consistent with this feature of the model), while imports plunge. Despite an improvement in net exports, economic activity drops sharply as domestic purchases plummet. Overall, the model predicts significant adverse effects on EME activity owing to the sudden stop of capital flows. As one might expect, these adverse effects are estimated to be much larger if the capital outflow pressure remains elevated, with the drag on EME GDP reaching nearly 6 percent by mid-2021.

Loosening Monetary Policy Can Help

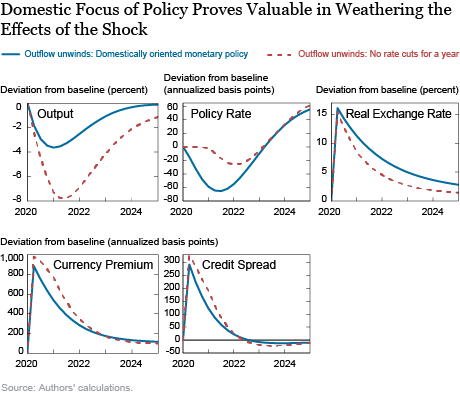

Our baseline simulation assumes a domestically oriented monetary policy rule, which implies that EME monetary authorities ease policy substantially in the wake of the sudden stop (see recent academic research for the role of financial policies in EMEs in these circumstances). Our model shows that loosening monetary policy can help mitigate the adverse effects of the sudden stop in flows.

To illustrate, as shown in the chart below, we assume an alternative scenario in which EME central banks avoid cutting rates for a year after the onset of the shock, perhaps motivated by fears that such easings would exacerbate capital outflows and currency depreciation. GDP drops precipitously, more than twice as much compared to a loosening of policy, despite the presence of dollar-denominated debt. The reason is that for the typical borrower, currency depreciation raises the value of just a fraction of liabilities, while contractionary policy triggers a general decline in domestic asset prices, adversely affecting the typical firm.

In fact, tight policy can be particularly perverse in this environment. Our model predicts that capital outflows accelerate when local balance sheets weaken, as global lenders become even more leery of lending to these borrowers. This explains the wider local currency premium in the “no rate cuts” scenario, which works to offset the effect of the higher policy rate on the exchange rate. The net effect is a nearly unchanged path of the exchange rate under the tighter policy, at the cost of a much more severe output contraction. In short, cutting too little too late has devastating real consequences, at little gain in terms of exchange rate stability.(1)

Spillbacks to the United States Operate through Trade and Financial Channels

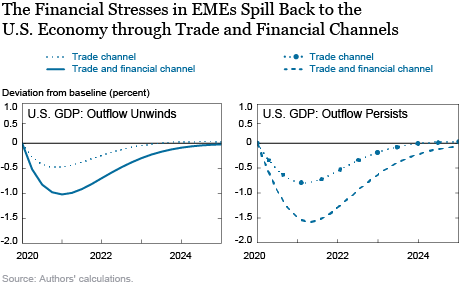

Our model estimates that the sudden stop in EMEs impacts the U.S. economy through both trade and financial channels, as shown in the chart below.(2)

The trade channel operates through a fall in U.S. exports owing to lower foreign demand, both because EME domestic purchases plummet and because U.S. goods become more expensive as the dollar appreciates. Overall, U.S. GDP declines by about 0.75 percent below the baseline solely due to the trade channel in the scenario in which EME capital outflow pressures persist.

The financial channel operates through U.S. banks’ balance sheet exposure to EME risks. As discussed earlier, the sudden stop causes a sharp fall in returns on EME assets. Lower returns on these assets, in turn, erode the value of some U.S. bank assets, causing the financial accelerator to kick in: the initial drop to bank asset values is amplified to cause a fall in economy-wide asset prices, generating higher U.S. credit spreads and lower investment spending. This channel also brings GDP down 0.75 percent relative to the baseline. As a result, in the scenario in which EME outflow pressure persists, U.S. GDP falls 1.5 percent below the baseline by early 2021, as both U.S. exports and investment spending decline. It is also important to note that the hit to U.S. GDP is quite persistent, since financial conditions remain fragile for some time.

One can argue that the model’s estimate for the magnitude of spillbacks likely constitutes a lower bound. First, we abstract from indirect exposures of U.S. banks’ balance sheets to EME risks through other advanced economies, especially the United Kingdom, Germany, and France. Second, the model does not consider supply-side effects linked with global supply chains, of which many EMEs are an important part. One would expect such effects to contribute to a larger and more persistent drag on the U.S. economic outlook.

Currency Swaps Can Mitigate the Financial Shock

In the model, the initiating shock is a sharp increase in the cost of accessing dollar funding markets (see, for example, the Jackson Hole paper by Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan and recent empirical research). The model captures the impact of this shock on both the financial and nonfinancial sectors in EMEs needing to roll over their dollar debt.(3) EME borrowers have to substitute dollar funding needs with domestically sourced funding, but the cost of the latter skyrockets due to deteriorating balance sheet conditions. The economy thus suffers a downturn caused by firms losing access to dollar funding. The local currency depreciation caused by the economic slowdown weakens balance sheets further—generating a downward spiral in which weakening balance sheets and a depreciating currency reinforce each other. In this environment, timely provision of dollar liquidity to illiquid borrowers can help dampen the downward spiral. The model suggests the net benefits of liquidity provision policies are increasing in the stress in credit markets induced by the shock (see, for example, the analysis of liquidity facilities in academic research we build upon).

In this regard, facilities such as the swap lines and the FIMA (foreign and international monetary authorities) repo facilities set up by the Federal Reserve have helped support the smooth functioning of dollar funding markets around the world and thus reduced the likelihood that EMEs will face acute dollar funding outflows. This should moderate some of the negative macroeconomic effects of the capital outflows on their own economies by curtailing the rise in credit spreads. Success in doing so would also limit the adverse spillbacks to output and employment in the United States. However, the swap lines and FIMA repo facility are designed to address short-term liquidity problems faced by solvent borrowers. Other policy actions currently being taken—such as the new International Monetary Fund (IMF) programs to address longer-term balance-of-payments issues and the debt repayment standstills agreed to by the G-20—will also prove helpful in addressing the deeper and more prolonged distress that some EMEs may experience as a consequence of the pandemic and its global economic effects.

(1) According to the IMF’s Policy Tracker, several EMEs have eased monetary policy somewhat in response to the COVID-19 sudden stop. However, as documented in Goldberg and Hamerling (2020), “How COVID-19 Pressures on International Capital Flows Stack Up,” EMEs have generally cut rates by less than advanced economies in the wake of the COVID-19 shock.

(2) In our model, the share in GDP of U.S. exports to the EME bloc (which consists of a broad set of emerging economies, including China), and vice versa, is calibrated using recent data from the IMF’s Direction of Trade statistics. Regarding the financial sector, in the model, EME assets constitute 5 percent of total U.S. banks’ assets, consistent with data from the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) consolidated banking statistics as of year-end 2019.

(3) Our model abstracts from some of the specific details related to the dollar funding issue. For example, the BIS in several research papers emphasizes the importance of dollar funding coming from credit-intensive global value chains, and the hedging needs of non-bank actors in the foreign exchange swap market to hedge U.S. credit risk.

Ozge Akinci is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gianluca Benigno is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Albert Queralto is a principal economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

How to cite this post:

Ozge Akinci, Gianluca Benigno, and Albert Queralto, “Modeling the Global Effects of the COVID-19 Sudden Stop in Capital Flows,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 18, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/05/modeling-the-global-effects-of-the-covid-19-sudden-stop-in-capital-flows.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Leslie: First of all, thanks a lot for your comments and your interest in our work. On the first point, we want to emphasize two key features of our model. First, we consider a two-region model (consisting of the U.S. economy and a set of emerging economies), where these two regions are interlinked through both international trade and cross-border lending. Goods produced in the U.S. and those produced in emerging economies are imperfect substitutes. In this respect, from the emerging economies’ point of view, demand for their goods from the U.S. is not infinitely elastic – the volume of exports is determined jointly by demand and supply. Second, we assume dominant currency pricing. This means that export prices are set in dollars, and sticky in the short-term. For this reason, the expenditure-switching effect of currency depreciation is much weaker than in the classical Mundell-Fleming framework (which assumes producer currency pricing). On your second point, the risk premium is only partly determined exogenously. It is important to note that the risk premium also reacts endogenously to the state of private-sector balance sheet conditions in the domestic economy. A monetary policy tightening in response to a risk premium shock, to the extent that it pushes down economy-wide asset prices and asset valuations of private sector banks and firms, will cause a further increase in the risk premium in these economies. As we note in the text, for the typical borrowing firm a currency depreciation raises the value of just a fraction of its liabilities (since part, but not all, of the average firm’s debt is in dollars), but a monetary tightening adversely affects the value of all of its assets – thus still weakening its balance sheet, despite the presence of foreign-currency liabilities, and thereby prompting a further rise in the risk premium.

I find a couple of points at least counter-intuitive and possibly erroneous. First, the sentence saying that since EM economies price exports in dollars a depreciation doesn’t help much on competitiveness. This shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the conventional small country model (and almost all countries are small countries insofar as they have little monopoly power). In this model all traded goods are priced in FX. Therefore the exports are determined by a supply curve–i.e., marginal cost–as demand is infinitely elastic. (Obviously imports are determined by a demand curve with supply infinitely elastic.) A depreciation helps exports by increasing profits in this sector as long as wages are sticky in local currency. There are many good arguments for the broad applicability of this model over any extended period, but you are in good company in getting it wrong. Second, if the shock to the system is a risk premium shock–either a currency risk premium or a default risk premium–then there are only two options: raise interest rates to reflect the change, or let the currency drop sufficiently to restore equilibrium. Your easy money solution will mean the latter. Great if debt is in local currency. A disaster if it is in dollars or euro–the quintessential fear-of-floating case.