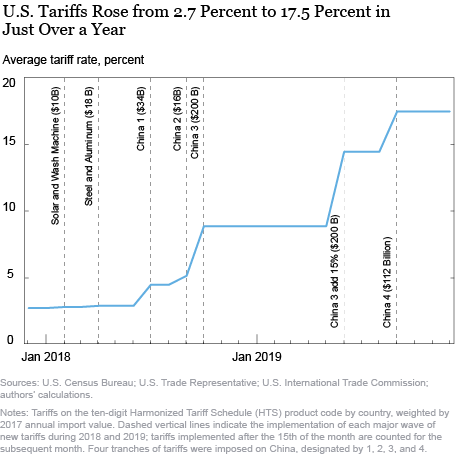

Starting in early 2018, the U.S. government imposed tariffs on over $300 billion of U.S. imports from China, increasing the average tariff rate from 2.7 percent to 17.5 percent. Much of the escalation in tariffs occurred in the second and third quarters of 2019. In response, the Chinese government retaliated, increasing the average tariff applied on U.S. exports from 5.7 percent to 20.4 percent. Our new study finds that the trade war reduced U.S. investment growth by 0.3 percentage points by the end of 2019, and is expected to shave another 1.6 percentage points off of investment growth by the end of 2020. In this post, we review our study of the trade war’s effect on U.S. investment.

Assessing U.S. Firm Exposure to China

This substantial rise in bilateral tariffs is likely to have affected the expected profitability of U.S. firms through a number of channels. First, our previous research has demonstrated that U.S. firms bore virtually all of the cost of higher U.S. import duties, which likely reduced the expected profitability of their operations. Second, U.S. firms that export to China, either directly or through their subsidiaries, became less profitable because Chinese tariffs made them less competitive. Third, the trade war seems to have caused a slowing of the Chinese economy, which, in conjunction with the possibility of China imposing new non-tariff barriers on U.S. firms, likely diminished the returns firms made on investments in the Chinese market.

The adverse impacts of the trade war have not only affected firms that trade with China; U.S. multinationals have likely been affected as well through their subsidiaries. Discussions of the trade war often focus only on U.S. exports to and imports from China, missing the much larger exposure of U.S. firms emanating from their subsidiaries in China. For example, while the United States only exported $130 billion of goods to China in 2017, sales by U.S. multinationals in China amounted to $376 billion that year. Although the large bilateral deficit in 2017 was driven by the fact that U.S. exports to China were only a quarter as large as Chinese exports to the United States, total sales (exports plus multinational sales) by U.S. firms in China were $505 billion—only 11 percent lower than total sales by Chinese firms in the U.S. market ($570 billion). Indeed, 46 percent of the 3,000 U.S. listed firms in our sample (which encompasses virtually all of U.S. market capitalization) were exposed to China through importing, exporting, or selling through subsidiaries, and the average firm obtained 2.3 percent of its revenues from China.

In addition to affecting U.S. firms that are directly exposed to China, the trade war can affect U.S. firms that do not trade with China. Some of these firms could benefit from trade war frictions, as U.S. tariff announcements may have raised the expected profits of domestic firms that compete with Chinese imports. Other firms may have been adversely affected through a number of channels. For example, heightened trade policy uncertainty and reduced demand from firms that are dependent on the Chinese market may have affected the profitability of firms that were not directly exposed to China. Moreover, their U.S. suppliers may have raised prices, either because they import from China or because they could increase markups due to a decrease in import competition.

Trade Tensions and Firm Profitability

These reductions in expected firm profitability are likely to have adversely affected investment by reducing expected returns and by forcing firms to incur the adjustment costs associated with writing off their investments in global linkages and supply chains. We estimate the importance of this channel by first estimating the impacts of U.S.-China trade-war announcements on expected firm profitability, and then estimating the impact of movements in profitability on investment.

Understanding the link between tariff announcements and profitability requires us to measure expected profits and identify whether a firm is exposed to China. As is standard practice, we use changes in stock prices as a proxy for changes in expected profits. We consider what happens to stock prices around the time of “trade war” announcement dates, which we define as days in which there were spikes in Google searches for the phrase “trade war.” We define the group of firms that are exposed to China as those that import from, export to, or have sales in China. We take into account that this exposure may arise because a firm directly transacts with China or does so indirectly through its subsidiaries or supply chains.

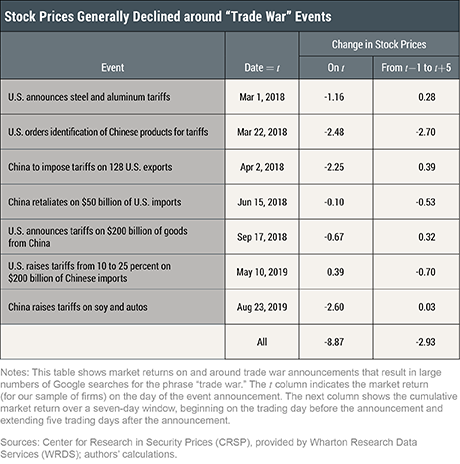

As one can see in the table below, these U.S.-China announcements were, on average, associated with substantial stock market declines. If we just look at returns on the days of announcements, we find that there was an 8.9 percent decline in stock prices for the firms in our sample. Instead, if we look at the returns over a seven-trading-day window—starting the day before the announcement and extending to five days afterward—we find that the market was still down 2.9 percent. Thus, even though there was some bounce-back following U.S.-China announcements, they served to lower the expected profits of listed firms, on net.

Using a new methodology, we consider two channels through which the U.S.-China trade war may have caused these movements. First, trade war announcements may have affected expected profits by affecting “common” factors that affect stock market returns in general: greater policy uncertainty, changes in expected economic conditions, etcetera. Second, trade war announcements are likely to have had “differential” effects on firms that were exposed to China in some way relative to firms that did not transact substantially with China.

Impact on Equity Prices and Investment Growth

We estimate that, jointly, these two channels depressed equity prices by 6 percent, translating into a $1.7 trillion loss in market capitalization for the firms in our sample. Of that 6 percent drop, we attribute 3.4 percentage points to the impact of trade war announcements on common factors and 2.6 percentage points to the differential impact of those announcements on U.S. firms with direct exposure to China.

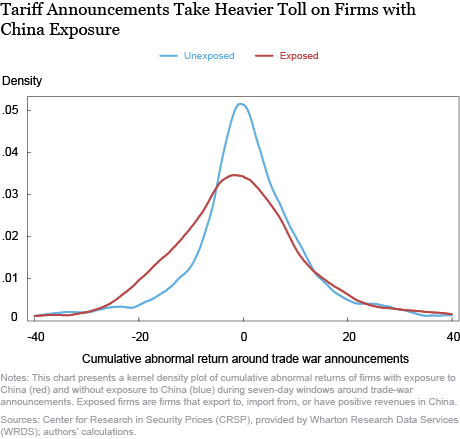

We can see these differential effects in the chart below, which plots “cumulative abnormal returns” after tariff announcements for listed U.S. firms with and without exposure to China. We see that the distribution of abnormal returns for exposed firms is shifted to the left, which means that exposed firms, on average, had lower returns than unexposed firms following a tariff announcement. In other words, these announcements lowered relative expected profits for exposed firms. Interestingly, our study did not find any evidence of beneficial effects for protected firms, those whose main source of sales revenue coincided with a sector receiving tariff protection.

We directly link these effects to a firm’s market-to-book value, which in turn affects that firm’s investment outlays. The positive relationship between market-to-book values and investment is well established in the literature. What is novel in our study is that we link our estimated effects of the trade war on abnormal returns to firm-level market-to-book value, so that we can calculate the aggregate investment effects of the trade war.

In sum, we find that the U.S.-China trade war lowered the market capitalization of U.S. listed firms by $1.7 trillion and will lower their investment growth rate by 1.9 percentage points by the end of 2020.

Mary Amiti is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sang Hoon Kong is an economics Ph.D. student at Columbia University.

David E. Weinstein is the Carl S. Shoup Professor of the Japanese Economy at Columbia University.

How to cite this post:

Mary Amiti, Sang Hoon Kong, and David E. Weinstein, “The Investment Cost of the U.S.-China Trade War,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 28, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/05/the-investment-cost-of-the-us-china-trade-war.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics