Many students are reconsidering their decision to go to college in the fall due to the coronavirus pandemic. Indeed, college enrollment is expected to be down sharply as a growing number of would-be college students consider taking a gap year. In part, this pullback reflects concerns about health and safety if colleges resume in-person classes, or missing out on the “college experience” if classes are held online. In addition, poor labor market prospects due to staggeringly high unemployment may be leading some to conclude that college is no longer worth it in this economic environment. In this post, we provide an economic perspective on going to college during the pandemic. Perhaps surprisingly, we find that the return to college actually increases, largely because the opportunity cost of attending school has declined. Furthermore, we show there are sizeable hidden costs to delaying college that erode the value of a college degree, even in the current economic environment. In fact, we estimate that taking a gap year reduces the return to college by a quarter and can cost tens of thousands of dollars in lost lifetime earnings.

The Return to College during the Pandemic

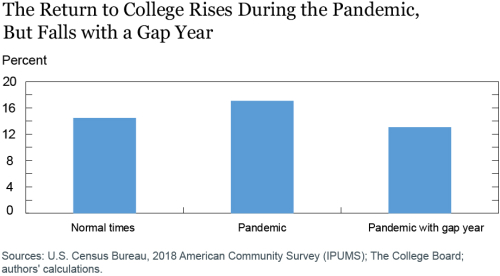

Despite rising costs, we have shown that college has remained a good investment, at least for most people, when we weigh the costs against the benefits during normal times. The economic costs of college include direct costs, such as tuition and fees, as well as opportunity costs—the wages one gives up while in school. The economic benefit of college is the college wage premium—the extra wages one can expect to earn with a college degree compared to having only a high school diploma, summed up over an entire working career. Because the costs and benefits of college accrue over different time intervals, we calculate the internal rate of return to weigh the upfront costs against the lifetime benefits. Before the pandemic, during more normal times, we estimate the return to college at about 14 percent, easily surpassing the threshold for a good investment. Importantly, we can’t rule out the possibility that some of what we estimate as the return to college is not a consequence of the knowledge and skills acquired while in school, but rather is a reflection of the innate skills and abilities possessed by those who complete college. Our estimates are in line with an extensive body of research that is better able to correct for such possibilities.

However, nothing is normal in the current economic environment. Unemployment has skyrocketed, and there are signs that wages for some workers are falling. How does this change the return to college?

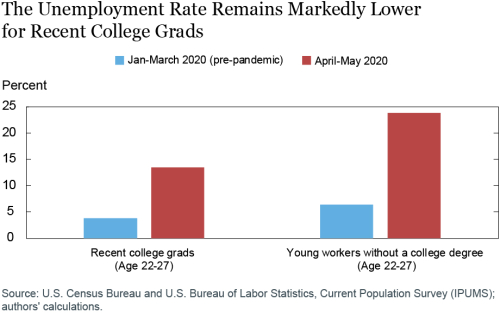

Let’s start with the costs. As we have shown before, opportunity costs are, by far, the largest cost of college. Importantly, however, these costs have fallen considerably due to the adverse shock to the labor market. Indeed, as the chart below shows, unemployment increased sharply after the pandemic hit, but particularly for those without a college degree. Indeed, about a quarter of young workers without a college degree did not have a job in the months immediately following the onset of the pandemic. The economic reasoning for the decline in opportunity costs is straightforward: if you can’t find a job, going to school is less costly. Another cost is, of course, tuition, which, if anything, may also decline next fall, as many schools have announced that they are cutting tuition in an effort to attract students, though perhaps only temporarily.

Turning to the benefits of college, despite greater uncertainty about the path of future earnings, there is little reason to think that the college wage premium will shrink. Though the wages of all workers may stagnate or even decline during recessions, they tend to fall as much or more for those without a college degree—and, importantly, it’s the gap that determines the college wage premium. This trend is likely to be especially pronounced during the pandemic, which has disproportionately reduced low-wage, high-contact jobs, the bulk of which are held by those without a college degree. Indeed, the increase in unemployment due to the pandemic was not nearly as steep for college graduates, as many of the jobs that typically require a college degree can more easily be done from home.

To re-estimate the return to college during the pandemic, we make one simplifying assumption: that workers with only a high school diploma are not able to find a job during the next year (we hold tuition constant to make a conservative estimate). This results in opportunity costs falling to zero for one year. As the chart below shows, this decline in opportunity costs alone increases the return to college to 17 percent, which is about 20 percent higher than in normal times. However, the chart also shows that taking a gap year during the pandemic reduces this return significantly, an issue we turn to next.

A Gap Year Can Be Costly

There are sizeable hidden costs to delaying college, even if only for a year. First, you give up a year’s worth of wages that could have been earned with a college degree had you graduated a year earlier. Second, if you enter the job market a year later, it damages your entire lifetime earnings profile because you miss out on the experience and the extra push that gives your wages over your working life, creating an earnings wedge each year. In essence, entering the job market a year later puts you behind for your entire career and you never really catch up.

Let’s take an example to illustrate this second point using our estimates. Someone who finishes a college degree in four years at the age of 22 would earn, on average, about $43,000 their first year on the job. By the time that person reaches the age of 25, they would earn an average of $52,000, having racked up three years of experience and commensurate raises. A graduate who delayed college by a year starts working at age 23, but would earn the same starting wage of a comparable graduate who took no delay. At the age of 25, a gap-year graduate would earn $49,000 compared to around $52,000 for the peer who graduated a year earlier, roughly $3,000 less. Being a year behind, these differences add up each and every year, so that those graduating later never catch up to those who graduated earlier. Together, these costs add up to more than $90,000 over one’s working life, which erodes the value of a college degree. We find taking a gap year cuts the return to college by a quarter to about 13 percent. No doubt, this return crosses the threshold for a good investment, but delaying college during the pandemic takes a financial toll.

Think Twice before Delaying

Of course, the return to college is not the only factor to consider when deciding whether to go to college, or the right time to do so. Health and safety are important considerations that our analysis does not take into account. In addition, if college is mostly online next year, the quality of instruction may be impacted and students might not build the skills they would with in-person classes. (Of course, this would not be a concern if college is just a signaling device, as some argue.) Moreover, recent research suggests at least some of the payoff to college comes from the network that is developed through personal relationships while in school, which could be damaged with extensive remote instruction. Furthermore, our analysis does not consider the consumption value of college—that is, missing out on the “college experience”—which may also be important for many students. And, finally, tuition may simply be out of reach for some families facing economic hardships during this time. Nonetheless, given the high cost of a gap year, perhaps some students will think twice before delaying.

Jaison R. Abel is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jaison R. Abel is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz, “Delaying College During the Pandemic Can Be Costly,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, July 13, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/07/delaying-college-during-the-pandemic-can-be-costly.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics