In response to disorderly market conditions in mid-March 2020, the Federal Reserve began an asset purchase program designed to improve market functioning in the Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) markets. The 2020 purchases have no parallel, but there are several instances of large SOMA purchases undertaken to support Treasury market functions in earlier decades. This post recaps three such episodes, one in 1939 at the start of World War II, one in 1958 in connection with a poorly received Treasury financing, and a third in 1970, also in connection with a Treasury financing. The three episodes, together with the more recent intervention, demonstrate the Fed’s long-standing and continuing commitment to the maintenance of orderly market functioning in markets where it conducts monetary policy operations—formerly limited to the Treasury market, but now also including the agency MBS market.

The 2020 Market Intervention

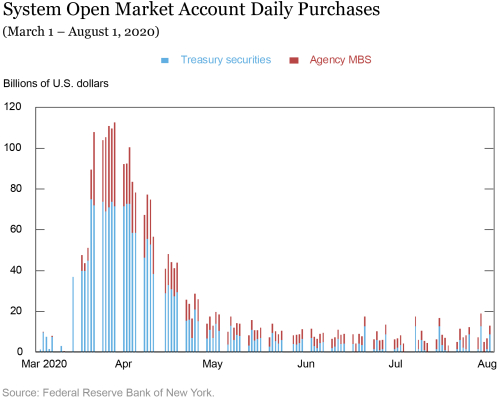

The Federal Reserve’s System Open Market Account (SOMA) holdings of U.S. Treasury and agency MBS expanded at an extraordinary pace beginning on March 13, 2020, with purchases totaling more than $100 billion on some days (see chart). Severe disruptions in Treasury market functioning, discussed here, and in the agency MBS market, discussed here, triggered the interventions. Cumulative purchases between March 13 and July 31 amounted to $1.77 trillion of Treasuries and $892 billion of agency MBS. The purchases were undertaken by the Open Market Trading Desk (the Desk) at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, acting on instructions from the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to make purchases “in the amounts needed to support [and subsequently sustain] the smooth functioning of [the Treasury and agency MBS] markets.”

The manager of the Open Market Account, Lorie Logan, recently commented on the “unprecedented scale and speed” of the March purchases. Logan observed that, “in early to mid-March, amid extreme volatility across the financial system, the functioning of Treasury and agency MBS markets became severely impaired” and that “continued dysfunction would have led to an even deeper and broader seizing up of credit markets and ultimately worsened the financial hardships that many Americans have been experiencing as a result of the pandemic.” She further noted how the responsiveness of the Desk’s interventions to evolving market conditions contributed to meeting the Committee’s objectives.

Origins of Federal Reserve Concern with an Orderly Treasury Market

Whether the Federal Reserve System has some responsibility for maintaining an orderly market for U.S. Treasury securities was first discussed in the December 21, 1936, FOMC meeting, where, as recounted in the minutes of the meeting:

… it was brought out that, in addition to its operations to serve general credit policy, the Reserve System had some responsibility for the maintenance of an orderly money market, and that in recent years the government security market had become so large a part of the money market that the general responsibility for the money market involves some measure of responsibility for avoiding disorderly conditions in the government security market.

In an April 1939 memo to the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, written in anticipation of a war in Europe, Allan Sproul, the First Vice President of the Bank and interim manager of the Open Market Account, observed that “we have an obligation … to facilitate an orderly adjustment of [the Treasury] market to new conditions.”

The September 1939 Intervention

World War II began on Friday, September 1, 1939. The onset of war was not unanticipated—Britain had suspended gold payments a week earlier and Treasury bond prices had fallen about two points since mid-August—but nevertheless converted what had been a likely prospect into a concrete fact. Treasury bond prices fell another 4½ to 6½ points during the first three weeks of September.

In an effort to buffer the price decline and maintain an orderly market, the Desk purchased $800 million of Treasury securities during the first two weeks of September. The purchase program was the largest to date, exceeding both a $157 million purchase program in the fall of 1929 and a $640 million program in the spring of 1932. The selling abated at the end of September and prices thereafter rose to the end of the year, recovering all but about a point of the losses incurred since mid-August.

The July 1958 Intervention

Following the Treasury-Federal Reserve Accord of March 1951, the FOMC examined how it could best move on from its wartime and post-war policy of fixing upper limits on Treasury yields (discussed here) and recapture control of bank reserves. In March 1953, the Committee voted to limit its operations in the Treasury market to short-term securities, except when intervention in longer-term markets was necessary to correct a disorderly market.

On Thursday, July 17, 1958, Treasury officials announced an exchange offering of 1-year certificates of indebtedness to refinance $16.2 billion of maturing securities. (In an exchange offering, investors paid for new securities by tendering maturing securities on a par-for-par basis. Cash purchases were not allowed.)

At midday on July 18, Robert Rouse, the manager of the System Open Market Account, received a call from Under Secretary of the Treasury Julian Baird. Prices in the Treasury market were “drifting lower,” Baird said, and “a condition was developing which the Treasury could not, in its opinion, hope to deal with.” Baird thought the problem “was a responsibility of the Federal Reserve System.”

Shortly thereafter Rouse suggested, in a conference call with FOMC members, that while trading was not disorderly, the Committee should nevertheless “authorize purchases of bonds for the [Open Market] Account … in order to steady the market.” Al Hayes, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, thought the market was pretty close to disorderly and, in view of Treasury’s concern with the “incipient failure of its financing,” backed Rouse’s recommended course of action. The minutes of the meeting state that Chairman William McChesney Martin supported Rouse’s proposal “reluctantly.” Other Committee members went along as well and the Committee authorized the purchase of up to $50 million “of government securities at the discretion of the manager of the System Open Market Account … wherever the manager deemed it appropriate in order to stabilize the market.”

Barely an hour later the Committee was back in session. As recounted in the minutes of the meeting, Rouse explained that “selling in the government securities market was increasing…. Bids were disappearing and about the only bids were those put in by the Desk. Indications were that volume was getting to be considerable.” His colleague, John Larkin, elaborated on the deteriorating situation:

At the conclusion of the last Committee meeting the [Desk] was informed by several leaders in the business that there were almost no bids …. Until recently, the selling seemed to be mostly speculative-type selling. However, with prices falling and dealers withdrawing their bids, there were reports of increasing institutional selling…. Dealers were reporting that the market was tending to feed on itself.

Rouse told the Committee that “he would now have to call the market disorderly” and that the $50 million authorized earlier was no longer adequate. Watrous Irons, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, agreed that “means must be taken by the System to restore stability.” Martin proposed that the Committee give Rouse “maximum discretion to handle the situation in the way he thought best.”

Following a unanimous vote to authorize “purchase for the System Open Market Account in the open market, without limitation, government securities in addition to short-term government Securities,” the Desk bought $32 million of securities before the close of trading. The intervention reversed the earlier price decline and the market closed unchanged on the day. Bankers hailed the action as “a necessary move to meet a market situation with which the Treasury was unable to cope.”

Subscription books for the exchange offering opened on Monday, July 21. Although market prices were generally firm, large secondary market offerings of the maturing securities soon appeared. The sellers were turning down the opportunity to exchange the securities for the 1-year certificates that the Treasury was offering, choosing instead to reinvest in higher yielding intermediate-term issues. Attrition (from securities not tendered for exchange that would have to be redeemed with cash) seemed likely to be quite high, potentially creating a cash flow problem for the Treasury.

During an 11 a.m. FOMC conference call, Larkin pointed out that “the situation was not one which would encourage the exchange of maturing securities.” Relying on the Committee’s Friday authorization, he said the Desk intended to support the Treasury offering, fearing that the refunding “could turn out to be the worst failure in the history of Treasury financing.”

The Desk began buying certificates on a when-issued basis on Monday afternoon when, in Larkin’s estimation, “the atmosphere got worse.” By the time the Committee met by telephone at 11 a.m. on Tuesday, the Desk had purchased more than $78 million of the certificates. Purchases exceeded $100 million before the meeting was over and exceeded $500 million on the day.

The Desk continued buying through Wednesday, July 23, the last day the subscription books were open. By the end of the day the Desk had bought, in aggregate, more than $1 billion of the certificates, $110 million of the maturing securities, and $65 million of other notes and bonds.

The May 1970 Intervention

On Wednesday, April 29, 1970, Paul Volcker, the Under Secretary of the Treasury for Monetary Affairs, announced the terms of the May refunding: a fixed-price cash subscription offering of $3.5 billion of 18-month notes and an exchange offering of 3-year and 6¾-year notes for $16.6 billion of maturing securities. Subscription books for the cash offering would be open for one day only, on Tuesday, May 5. The books for the exchange offering were set to close on May 6.

In a televised speech to the nation on April 30, President Richard Nixon announced that ground combat forces had crossed over from South Vietnam into Cambodia in a large-scale operation aimed at eliminating Communist sanctuaries. By Monday, May 4, anti-war protests had erupted at dozens of colleges, four students had been killed by National Guard troops at Kent State University in Ohio, and (in the words of the Wall Street Journal) “the bond markets were battered.” Treasury yields were 25 basis points higher and the refunding was in danger of failing.

On Tuesday, May 5, the Desk entered the market, buying what was described by the Wall Street Journal as “large quantities” of Treasury bills. The New York Times reported that “the Federal Reserve System was forced to make ‘massive’ purchases of securities in the open market to prevent the Treasury’s $3.5 billion sale of notes … from failing ….” The Desk purchased $1.5 billion of Treasury bills during the week ended May 6 and lent $1.2 billion on repurchase agreements.

Summing Up

The magnitude of the Desk’s purchase program in 2020 “to support the smooth functioning” of the Treasury and agency MBS markets marked those purchases as highly unusual. From an operational perspective the speed and size of the program were unprecedented, yet as a policy response, as the three episodes discussed here show, it was not unique. There may be other ways to forestall or mitigate the appearance of a disorderly, illiquid market, such as primary market auction sales of Treasury debt (which in the 1970s replaced the fixed-price offerings at the root of the 1958 and 1970 episodes) or improved clearing and settlement systems (which have been suggested in the wake of the 2020 purchase program), but the infrequency of Federal Reserve intervention suggests that relying on the Fed on those rare occasions when markets are in extremis has not materially exacerbated moral hazard.

Expanded and footnoted versions of the three episodes recounted in this Liberty Street Economics post will appear in “After the Accord: A History of Federal Reserve Open Market Operations, the U.S. Government Securities Market, and Treasury Debt Management from 1951 to 1979,” by Kenneth D. Garbade, to be published by Cambridge University Press next winter.

Kenneth D. Garbade is a senior vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Kenneth D. Garbade is a senior vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Frank M. Keane is a senior policy advisor and a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Frank M. Keane is a senior policy advisor and a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Related Reading on Liberty Street Economics:

How the Fed Managed the Treasury Yield Curve in the 1940s (April 6)

Treasury Market Liquidity during the COVID-19 Crisis (April 17)

MBS Market Dysfunctions in the Time of COVID-19 (July 17)

How to cite this post:

Kenneth D. Garbade and Frank M. Keane, “Market Function Purchases by the Federal Reserve,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, August 20, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/08/market-function-purchases-by-the-federal-reserve.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

This is a fascinating and masterful historical account, implying that the dysfunctionality of the Treasury market in March, on Covid news, was the fourth time in a century at which the Fed stepped in with purchases of Treasuries to help restore market liquidity. Although rare, this action by the Fed is completely in line with the intended role of a central bank during market-liquidity emergencies. I also recommend the book by Bill Allen, describing how the Bank of England has sometimes had to support the secondary market for gilts. I understand that Kenneth Garbade will soon be providing a book-length treatment of the history of the role of the Fed in the U.S. Treasury market. Going forward, given the soaring amount of marketable Treasury securities and the limited balance sheet space of major Treasury dealers, I anticipate the Fed will be forced to rescue the Treasury market more frequently in coming decades. The associated risks to financial stability, reduced safe-haven status of Treasuries and reserve-currency status of the U.S. dollar, and the resulting increased costs to U.S. taxpayers of funding U.S. deficits are a concern for policy makers. These risks could be mitigated by improving the infrastructure of the secondary market for Treasuries with measures such as central clearing. This could also eventually enable all-to-all trade, so as to allow more effective use of the limited balance sheet space of major dealers.