China’s export performance this year has been stronger than expected. After a sharp slump at the beginning of 2020, the country’s exports have posted positive growth—the only major economy’s to do so. However, a closer look at the data reveals that this growth has not been very broad-based, but rather concentrated in areas where China’s export structure was well-positioned to take advantage of the global crisis—namely, production of medical supplies and school-from-home and work-from-home (S/WFH) goods. Once the COVID-19 crisis passes, China’s exports will likely return to their pre-coronavirus growth path, including a gradual loss of market share to other countries.

China’s manufacturing production rebounded quickly and early from its lockdown

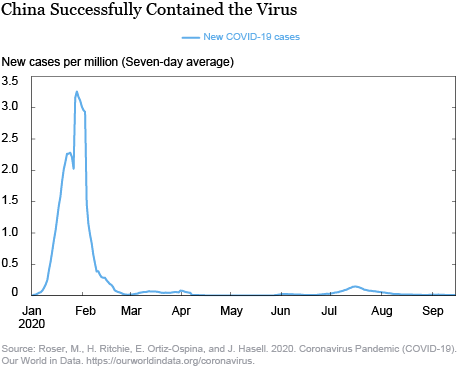

China was “first in, first out” of the global COVID-19 crisis. The country was the original epicenter of the crisis and implemented the world’s first economic lockdown on January 23. The chart below shows COVID-19 cases. China has followed essentially an “elimination” strategy for COVID-19, one of the only countries to do so successfully. New cases in China originally reached about three per million—concentrated especially in the city of Wuhan in Hubei province—but then began dropping a few weeks after a nationally comprehensive and strictly enforced economic “lockdown” began in the third week of January. As early as the middle of February the Chinese government began to re-open the economy. Since then, COVID-19 cases and deaths in China have, by all appearances, remained low.

Against this backdrop, China’s economy initially suffered a severe blow in the first quarter of this year as its lockdown led to a shutdown of much of its manufacturing, freight, transport, and shipping industries. GDP contracted by an estimated 37 percent on an annual basis, and China’s exports fell by 17 percent in the first two months of 2020 compared with the same period in 2019. However, with workplaces and transportation largely open by the around the end of the first quarter, China’s economy has quickly rebounded. GDP grew by nearly 60 percent in the second quarter on an annual basis, and, as of August, industrial production was 3 percent above its pre-lockdown level. Consumption and services have not rebounded as strongly, but even those sectors have been growing at a decent monthly clip.

China’s exports have been stronger than that of most (but not all) peers

Just as China’s economy was getting its footing back, the rest of the world was reeling as the COVID-19 crisis spread globally. Most forecasters accordingly expected that China’s exports would fall over a cliff due to collapsing foreign demand. For example, as of the end of April 2020, the median forecast for China’s exports called for an average decline in value terms of around 10 percent in the second and third quarters over the same quarters in 2019. As it turned out, exports slightly increased in the second quarter and are currently forecast to grow by close to 6 percent in the third and fourth quarters of this year.

Almost from the beginning, however, China’s exports beat expectations. The twelve-month change in China’s exports quickly turned positive and reached as high as nearly 10 percent in September. The chart below plots the twelve-month percent change in the rolling three-month average of China’s exports versus selected other countries in Asia as well as the world total (with the average helping to smooth out seasonal fluctuations). The chart shows the latest available data for each country, and through July for world trade. It is readily apparent that China’s exports have performed quite a bit better than that of its Asian peers and the world average. In fact, China’s exports actually have turned in their best year since 2018. At the same time, however, it is important to stress that China’s performance has not beat all of its competitors. For example, Taiwan and Malaysia have recorded positive growth, and Vietnam has even outperformed China somewhat.

The world needed PPE—and China’s export machine came to the rescue

To focus in on the drivers of this growth, this section will examine the data for August (detailed trade data are not yet available for September). In the discussion that follows, all percent changes are expressed as year-over-year growth rates of rolling three-month averages.

China’s exports grew by 5.8 percent in the three months ended in August compared with the same period in 2019. The chart below drills deeper into this growth by looking at the growth contributions at a more disaggregated level. As is readily apparent, by far the largest growth contributions came from the categories that are labeled “machinery” and “textiles” in the chart.

What are these categories, and what is driving them? Machinery should not be surprising and looms large in China’s trade, comprising fully 44 percent of China’s total goods exports. Narrowing down further into this category, we find that the strongest growth contributions by far came from computers, laptops, tablet computers, mobile phones, and similar types of goods, which grew by between 20 percent and 30 percent and contributed 2 percentage points to total export growth. Certain medical and surgical equipment comprises only about 1 percent of China’s exports but grew by somewhat over 70 percent and contributed another 0.4 percentage point. These trade flows clearly have been boosted primarily by S/WFH activities.

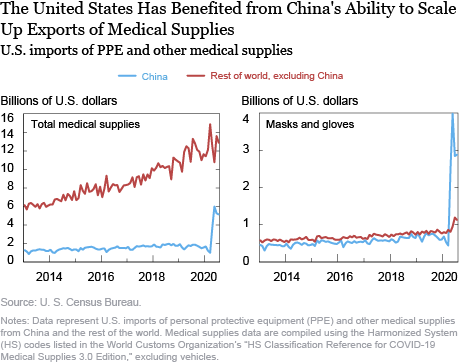

Growth in the “textile” category has been quite remarkable. This category of exports usually is not very exciting, comprising about 10 percent of total goods exports last year and long experiencing a declining share of China’s exports. But this area has been boosted by truly explosive growth of personal protective equipment (PPE) and similar medical gear for both household and medical professional use. In fact, China’s exports to the world of face masks alone grew by as much as over 3400 percent in May, and were still up 970 percent in August. As a result, this small sliver of China’s exports—only about 0.2 percent of the total in 2019—contributed as much as over 7 percentage points to China’s export growth in May, and still over 2 percentage points in August.

China’s role as the global supplier of medical supplies to the United States is particularly salient. The two panels in the chart below show U.S. imports of PPE and other medical supply-type goods from China and the rest of the world excluding China up through July. The left panel shows the total, and the right panel covers face and hand coverings. From steady levels before the crisis, total U.S. imports of these items jumped, with face and hand coverings increasing by nearly three times their average monthly level of last year. China has supplied nearly all of this increase. As a result, the United States has benefited enormously from China’s ability to ramp up, virtually on a dime, production of essential medical supplies.

China’s export engine may sputter as the COVID-19 shock passes

Is China’s export performance sustainable? The answer is a qualified “no,” at least in the medium-term and beyond.

First, a differential in policy responses between China and its major trading partners has played a major role in China’s export success. China’s own policy has revolved around a successful domestic containment of the coronavirus amid large-scale monetary, fiscal, and political support to get the country’s “manufacturing machine” up and running. At the same time, many of its major trading partners have been much less successful in controlling the coronavirus, but have been more successful in providing income transfers to their populations. The net result has been a massive and sustained demand for PPE, other medical equipment, and S/WFH-type products, which China was well-positioned and willing to provide.

However, China cannot expect to benefit indefinitely from these heterogeneous policy responses. Policy abroad will evolve in ways that likely will not be as beneficial to China. Already, income support programs are scaling back or ending in its major trading partners, which will probably reduce demand for China’s high-tech exports. China’s PPE exports are largely disposable and can likely sustain strong growth so long as populations abroad need them, but S/WFH goods are more durable and will likely weaken substantially once pent-up demand is satiated. Finally, foreign governments are actively seeking to source more medical supplies domestically, and medical breakthroughs eventually should bring an end to the COVID-19 crisis.

Once the special factors boosting China’s exports wane, one would expect a return to pre-crisis trends. Even before the COVID-19 crisis, the trade war with the United States had been incentivizing some firms to relocate supply chains outside of China, including to Vietnam. A gradual decline in China’s foreign market share will likely continue and could intensify as firms shift production chains or foreign governments actively implement policies to “onshore” production of certain critical goods into home markets. However, the sheer scale and flexibility of China’s manufacturing labor force means that it will remain a global export powerhouse for the foreseeable future.

Hunter L. Clark is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Hunter L. Clark, “COVID-19 Has Temporarily Supercharged China’s Export Machine,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 15, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/10/covid-19-has-temporarily-supercharged-chinas-export-machine.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics