As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in the United States, in just two months—between February and April 2020—the nation saw well over 20 million workers lose their jobs, an unprecedented 15 percent decline. Since then, substantial progress has been made, but employment still remains 5 percent below its pre-pandemic level. However, not all workers have been affected equally. This post is the first in a three-part series exploring disparities in labor market outcomes during the pandemic—and represents an extension of ongoing research into heterogeneities and inequalities in people’s experience across large segments of the economy including access to credit, health, housing, and education. Here we find that some workers were much more likely to lose their jobs than others, particularly lower-wage workers and those without a college degree, as well as women, minorities, and younger workers. However, as jobs have returned during the recovery, many of these differences have narrowed considerably, though some gaps are widening again as the labor market has weakened due to a renewed surge in the coronavirus. The next post in the series examines differences in patterns of commuting during the pandemic, and finds that workers in low-income and Black- and Hispanic-majority communities were more likely to commute for work. The final post in the series analyzes unemployment dynamics during the pandemic, and finds that Black workers experienced a lower job-finding rate and a higher separation rate into unemployment than white workers during the recovery, though this trend has reversed to some extent recently.

Low-Wage Workers Hit the Hardest

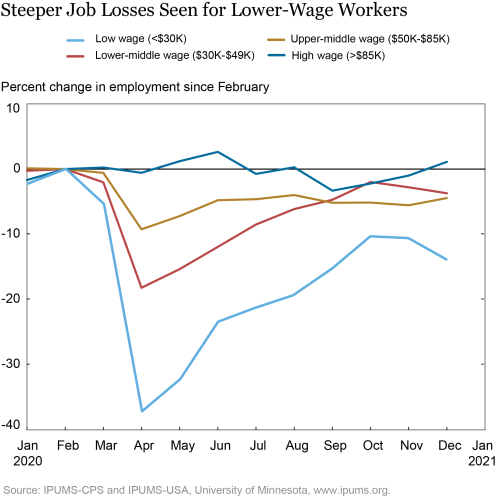

Lower-wage workers have borne much more of the brunt of job losses during the pandemic than higher-wage workers. To illustrate, we separate jobs into four categories based on each occupation’s median wage. Low-wage workers work in jobs that typically pay less than $30,000 annually, and include jobs such as food servers, cashiers, home health aides, and childcare workers. Lower-middle-wage workers work in jobs that typically pay between $30,000 and $50,000, and include jobs like administrative assistants, hairdressers, carpenters, and truck drivers. Upper-middle-wage workers work in jobs that typically pay between $50,000 and $85,000, including jobs such as teachers, police officers, accountants, and financial managers. High-wage workers are employed in jobs that typically pay over $85,000 per year, including software developers, engineers, lawyers, and business executives. For perspective, our high-wage and low-wage categories represent roughly the top and bottom 10 percent of workers, while the two middle-wage categories each cover about 40 percent of workers. As the chart below shows, between February and April 2020, employment declined by more than a third for low-wage workers, compared to a decline of 18 percent for lower-middle wage workers, and nine percent for upper-middle wage workers. By contrast, employment for high-wage workers held steady.

The economy returned a substantial number of jobs after bottoming out in April 2020, particularly for low-wage workers. This partial but strong recovery helped narrow the gap between low-wage workers and their higher-paid counterparts. However, employment for the two lower-wage groups began to decline again in October as the winter wave of the virus began, even as jobs for the two higher-wage groups grew, opening up the gap once more. All in all, employment among high-wage workers is now slightly above where it was before the pandemic hit, and employment among both middle-wage groups is just slightly below. By contrast, employment among low-wage workers remains 14 percent below pre-pandemic levels and is trending down again.

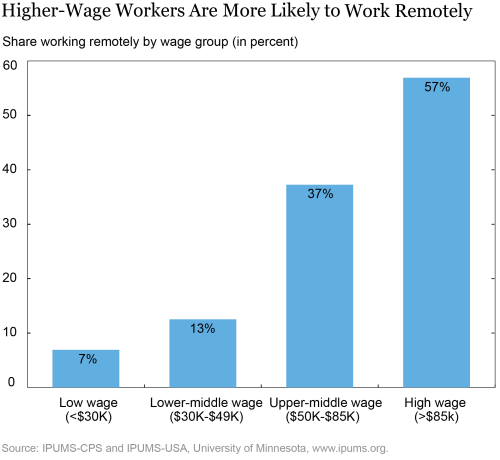

Why have lower-wage workers been hit so much harder during the pandemic? Much of it can be traced to differences in the types of jobs held among the groups. Due to a combination of government restrictions and behavioral changes people made to avoid exposure to the virus, the largest losses during the pandemic accrued to the leisure and hospitality industry—most notably, restaurants, bars, and hotels—as well as retail, both of which tend to employ large numbers of lower-paid workers. Further, lower-wage workers have much less ability to work remotely—think food servers and cashiers—compared to higher-wage workers, such as managers, accountants, and attorneys. In fact, according to new data collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics after the pandemic began, an average of nearly 60 percent of workers in our high-wage group reported that they telecommuted during the pandemic, compared to less than 10 percent for low-wage workers, as shown in the chart below. This pattern is consistent with findings by our colleagues in a related post showing that workers in low-income areas are more likely to commute to work than workers in high-income areas, suggesting that such workers are more dependent on occupations that require in-person work.

An Uneven Experience

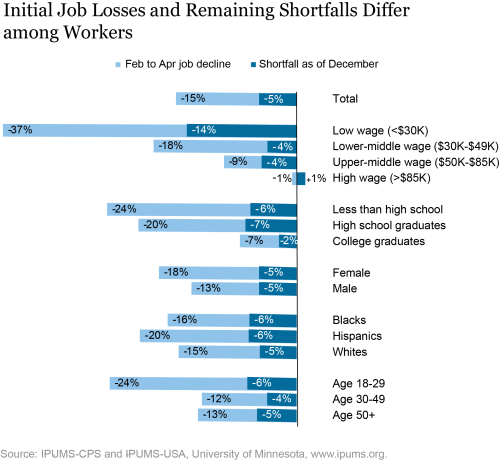

More broadly, employment outcomes through the pandemic have been highly uneven among different types of workers, as shown in the chart below. We group workers into categories based on educational attainment, race and ethnicity, gender, and age. While we find big differences in initial job losses across groups of workers, many of the initial gaps that opened have narrowed considerably through the recovery.

The length of each bar in the chart represents the magnitude of initial job loss, while the solid portion represents the remaining job shortfall at the end of 2020. Overall, for the nation as a whole, initial job losses totaled 15 percent and the remaining job shortfall is 5 percent. The first set of bars corresponds to workers of different wage levels, summarizing trends presented earlier. The next set of bars considers differences by educational attainment, and shows a similar pattern given the high correlation between education and wages. The least-educated workers—those without a high school diploma—saw employment fall by 24 percent, compared with 7 percent for workers with a college degree—a gap of 17 percentage points. By the end of 2020, job shortfalls totaled 6 to 7 percent for those without a college degree, compared with just two percent for those with a college degree—a smaller but still substantial gap of around 4 percentage points.

Looking across demographic groups, it is clear the pandemic caused outsized job losses for women, minorities, and younger workers as the pandemic took hold. Initial job losses among women were 4 percentage points higher than for men, and initial job losses among Black and Hispanic workers were several percentage points higher than for white workers. Furthermore, the pandemic has been quite challenging for younger workers (those under 30), with initial job losses nearly twice as large as mid-career (those aged 30 to 49) and older workers (those 50 and over).

These differences in job losses early in the pandemic reflect a combination of factors. First, some groups may be overrepresented in the two industries hit hardest by the pandemic—leisure and hospitality and retail—including younger workers and those without a college degree. Further, some jobs have been easier to hold onto than others, particularly those that can be done from home, and different groups may be overrepresented in jobs that can or cannot be performed remotely. College graduates, for example, tend to have more flexibility in their jobs and a greater ability to work remotely. And, a factor that may help explain the outsized job loss among women is that women tend to bear more of the burden of childcare responsibilities, which have increased significantly during the pandemic due, in part, to schools teaching online and many students at home. This factor may have contributed to a disproportionate share of women not working in order to care for their children. There may also be differences in the willingness to work among different groups given the dangers of COVID-19. However, it is difficult to determine the nature and magnitude of these influences.

Interestingly, consistent with recent research, most of the gaps across demographic groups have narrowed considerably during the recovery, particularly as jobs have been added in the hardest-hit sectors. The shortfall between men and women has closed completely, while the gap between Black and Hispanic workers relative to white workers has closed to one percentage point. This is consistent with research by our colleagues which finds that the job finding rate among Black workers has risen above the corresponding rate for white workers. And, the remaining jobs shortfall among younger workers has narrowed to within a couple of percentage points of mid-career and older workers. Unfortunately, as the job market began to weaken in late 2020 due to a renewed surge in the virus, there are signs that some of these gaps have begun to widen once more, as many of the most vulnerable workers are yet again being hit hardest.

Jaison R. Abel is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz, “Some Workers Have Been Hit Much Harder than Others by the Pandemic,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 9, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/02/some-workers-have-been-hit-much-harder-than-others-by-the-pandemic.html.

Related Reading

Which Workers Bear the Burden of Social Distancing Policies?

COVID-19: Information, Research and Analysis and Resources

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Mr.Abel: Will there be follow on research regarding the decrease in overall wage levels that have (or have not) been experienced by workers during the period 2020-2021? If the entire scale continues the “dual labor market” trends of the last thirty years, what will be the effects over the next five years, since we took quite long to recover wage levels after the 2008 debacle. I am an old man now, but have watched the labor share of the total economy shrink since at least 1975 (cf. Raj Chetty’s work). Will the pandemic effects in fact just deepen the effective loss of purchasing power by the 90 percent? All best wishes in your work Dave Thomas Feb. 16, 2021