The Main Street Lending Program was the last of the facilities launched by the Fed and Treasury to support the flow of credit during the COVID-19 pandemic. The others primarily targeted Wall Street borrowers; Main Street was for smaller firms that rely more on banks for credit. It was a complicated program that worked by purchasing loans and sharing risk with lenders. Despite its delayed launch, Main Street purchased more debt than any other facility and was accelerating when it closed in January 2021. This post first locates Main Street in the constellation of COVID-19 credit programs, then looks in detail at its design and usage with an eye toward any future programs.

Main Street in the Universe

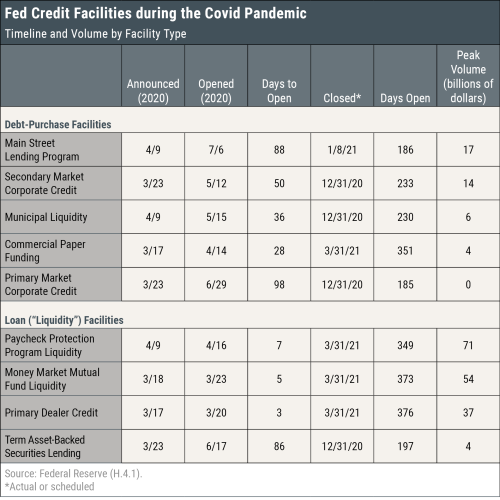

Facility space is a jumble of acronyms, so it is best navigated starting with the two types of programs (see table below). Purchase facilities buy debt; loan facilities lend directly. The latter are close cousins to traditional discount window lending, so the three launched last year (or rebooted from 2008) were up and running in just a few days. Purchase programs, by contrast, are newer (and potentially riskier), and so they took longer to build. Main Street required longer than most because it bought loans, a more complex, varied type of debt than the “vanilla” bonds or securities purchased by the other facilities. “It is far and away the biggest challenge of the … facilities,” Fed Chair Powell said during build-out.

It’s Not a Race, but…

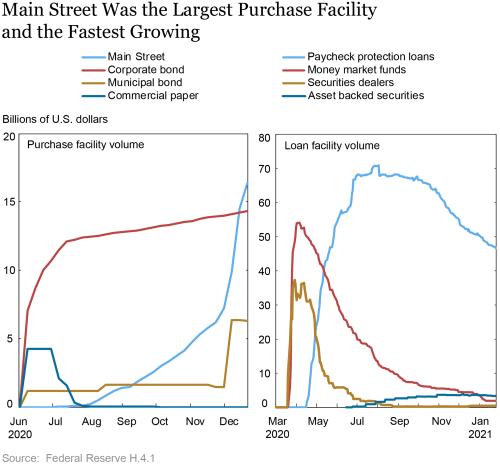

Main Street purchased more debt than the other facilities and accelerated across the finish line (see chart below). Its $17 billion in volume (as of December 31, 2020) pales compared to $525 billion in Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans cum grants but is close to the $18 billion by which small U.S. banks outside the largest twenty-five (as most Main Street banks were) in aggregate increased their stock of business loans every six months on average over 2010-19 (FRED).

Main Street Up Close

The design and funding of Main Street was a collaborative effort. Treasury committed $75 billion and bears first losses, an important consideration in the overall risk tolerance of the program. The public also contributed over 2,200 letters that prompted several changes to the program. The Boston Fed administers the program.

The guiding concept was risk sharing without oversharing. Lenders could sell 95 percent of new loans to the facility with losses (and earnings) shared proportionately. Risk sharing was supposed to mitigate the uncertainty (COVID “fog”) constraining loan supply and release bank capital (by reducing loans on banks’ books) to support new lending. Buying the whole loan might be going too far since lenders would have little incentive to screen and monitor credits or work out problem loans.

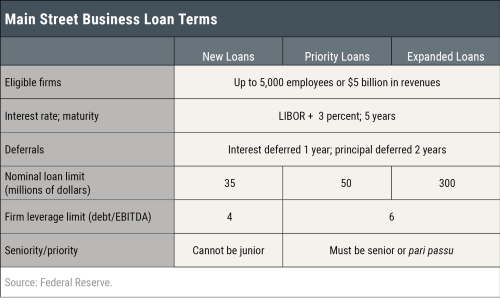

To accommodate the diversity in bank loans, Main Street purchased three types of loans (see table below). Priority Loans and Expanded Loans could be larger and their borrowers more levered than with New Loans but were also more senior in default events. Lenders had considerable leeway within those parameters except when it came to pricing; all loans, risky or safe, had to be at 3 percent over LIBOR. Main Street targeted mid-sized firms (up to 5,000 employees) that might be too large for the PPP yet too small to benefit from the “Wall Street” facilities. Only banks (and credit unions) were eligible to sell loans to the program. Nonbank (“shadow”) lenders such as finance companies and “fin techs” (financial technology) are not supervised by the Fed and specialize in riskier lending than banks (Chernenko et al.).

Lenders and Loans

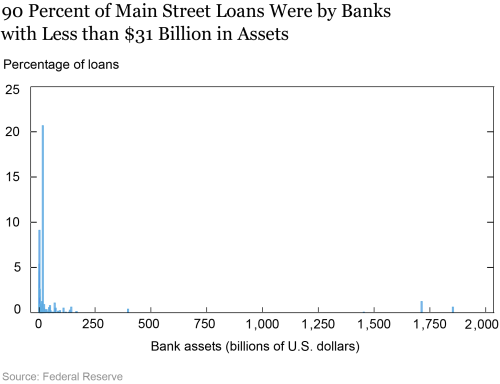

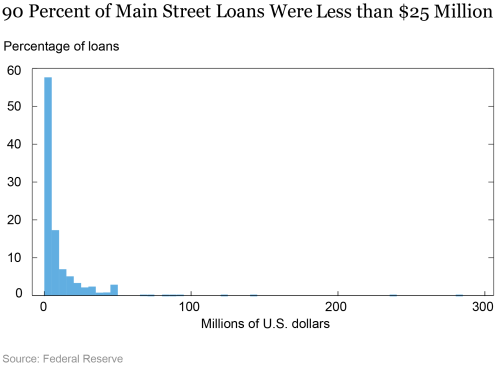

Main Street bought 1,810 loans from 312 lenders, virtually all banks. Three of the four U.S. banks with more than $1 trillion in assets participated but banks with less than $31 billion in assets accounted for 90 percent of loans sold (see chart below).

The average purchase was $9.1 million (see chart below). The average PPP loan was just $101,000 (Hubbard and Strain) so Main Street succeeded in targeting more medium-sized firms. Priority loans (which could be used for refinancing) accounted for two-thirds of loans and three-quarters of volume and New Loans most of the rest. Expanded Loans (which entailed re-writing existing loan agreements) were not much in demand.

Not a Dead End

Demand and supply help explain why Main Street did not go further. Senior loan officers reported contracting demand for business loans every quarter last year after the first quarter (recessions usually reduce loan demand). Main Street, a supply-side intervention, was pushing on a string.

While weak demand was arguably the biggest roadblock, some program features also sidetracked participants. Senior loan officers eschewing the program cited their uncertainty about how loss-sharing (the key feature) with the Fed and Treasury would play out. They reported that some borrowers were deterred (according to loan officers) by restrictions on salaries or dividends. The lack of risk-based pricing may have deterred some safer borrowers (Vardoulakis; English and Liang) though it did simplify matters. The overall risk tolerance of Main Street also mattered. A more aggressive facility would have reached more borrowers but with higher expected losses to taxpayers (Rosengren). These are considerations for any future Main Streets.

Don Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Steph Clampitt is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Donald P. Morgan and Steph Clampitt, “Up on Main Street,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 5, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/02/up-on-main-street.html.

Related Reading

Helping State and Local Governments Stay Liquid

The Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility

The Primary Dealer Credit Facility

The Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility (PPPLF)

The Primary and Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facilities

Securing Secured Finance: The Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility

Video: The Commercial Paper Funding Facility, Explained

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics