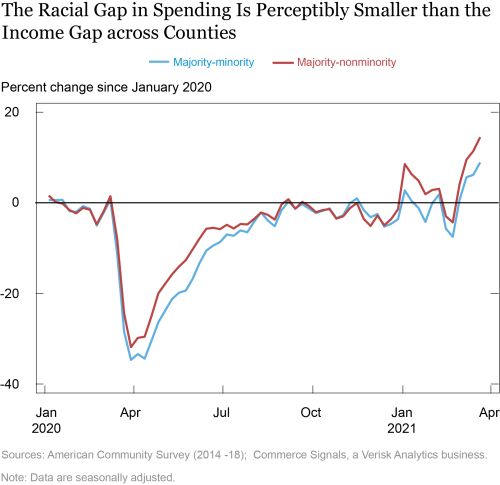

This post is the first in a two-part series that seeks to understand whether consumer spending patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic evolved differentially across counties by race and income. As the pandemic hit and social distancing restrictions were put into place in March 2020, consumer spending plummeted. Subsequently, as social distancing restrictions began to be relaxed later in spring 2020, consumer spending started to rebound. We find that higher-income counties had a considerably steeper decline and a shallower recovery than low-income counties did. The differences by race were also sizeable as the pandemic struck but became considerably more muted after summer of 2020. The decline and the recovery until the end of summer were sharper for majority-minority (MM) than majority nonminority (MNM) counties, while both sets of counties showed similar growth in spending after that. The second post in this series highlights the goods and services that were most adversely affected (or “constrained”) by the pandemic. Then, differentiating households by income, that post explores which households were more exposed to these pandemic-constrained expenditure categories.

Data and Background

We capture consumer spending by using detailed county-level card transaction data provided by Commerce Signals, a Verisk Analytics business. Commerce Signals captures spending by a permissioned panel of around 40 million U.S. households, which means that it includes data on spending at large businesses as well. The aggregate trends from Commerce Signals align well with national retail sales numbers. We use county-level Commerce Signals data to identify the differences in consumer spending between residents of low-income and higher-income counties and between residents in MM and MNM counties. Following earlier posts in our ongoing Economic Inequality series, we use data on race and income composition at the county level from the 2014-18 waves of the American Community Survey to differentiate between low-income and higher-income counties, and between MM and other counties. We define low-income counties as those that fall in the lowest quartile of the population-weighted distribution of median household income. Recognizing that the term “minority” does not fully capture the racial and ethnic diversity present, we note that in our definition MM counties are those in which at least half the population is Hispanic, and/or non-Hispanic Black, Asian American, Pacific Islander, or Native American. We seasonally adjust the data by dividing weekly data for each group by the corresponding data in 2019. Next, we index each series to January 2020 and rescale the series to present percent changes relative to January 2020. In other words, each spending series represents the year-on-year growth in spending relative to the year-on-year growth obtaining in January 2020.

Differences in Consumer Spending by Income

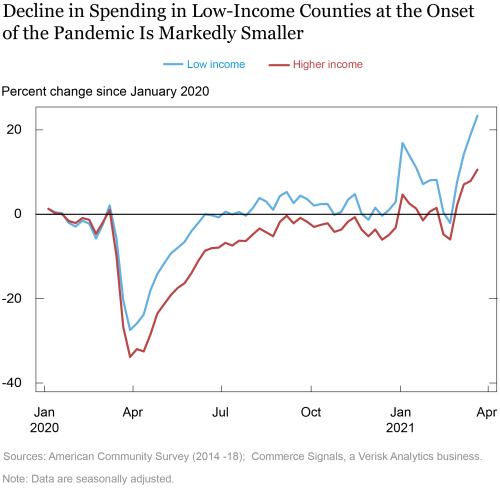

Here we consider two measures of spending: total spending and spending in restaurants and bars, looking first at the difference in total spending by median county income. We find that there is practically no difference in the pre-COVID period in consumer spending growth between low-income counties and other counties. Spending declines drastically across all counties in March 2020. Notably, though, the percentage decline in spending in low-income counties (relative to January 2020) was perceptibly smaller than that for higher-income counties. In other words, households in higher-income counties reduced their total consumption much more than households in low-income counties. The rebound in spending between April and June 2020 is also more rapid in low-income counties, which almost returns to pre-pandemic levels by July 2020. While the gap between both groups of counties began closing towards the last quarter of 2020, it widened around the holidays. As of the end of March 2021, seasonally adjusted consumption in both low-income and higher-income counties surpassed their pre-pandemic levels.

What might be the factors behind these differences? The composition of consumption differs considerably between high- and low-income households. Low-income households spend a greater proportion of their income on necessities, the demand for which is inelastic, and there is not much room for cutbacks even in cases of financial losses. Such households are also more likely to have lost jobs and received unemployment assistance and income support, which may have prevented deeper cuts. In contrast, a larger share of the consumption basket of higher income households pertain to goods and services that were hit the hardest by social distancing, for example: travel, hotels, and recreation. The decline in these industries during the pandemic constrained the consumption basket of the richer households relatively more, leading to a sharper decline in spending. Higher-income households may have also resorted to precautionary saving facing the uncertainties of the pandemic. Together, these factors help explain the smaller percentage decline in spending in low-income counties as the pandemic struck as well as a sharper return during recovery (see the chart below).

The story remains very similar when we only consider spending at restaurants and bars. The food service industry as a whole was greatly affected by the stay-at-home orders that most U.S. states announced at the onset of the pandemic. Consumer spending at restaurants and bars declined by an even greater magnitude than total spending. And when distinguishing by income, we see that just like total spending, spending in low-income counties declined less than in high-income counties and recovered noticeably faster. One explanation may be that restaurant types predominating in low-income counties (quick service or drive-throughs at fast food restaurants) would have been less affected by social distancing than those in high-income counties (sit-down dining). Spending in the higher-income group had not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels of seasonally adjusted consumption by the end of March 2021 (see the next chart).

More generally, these patterns should not be interpreted to mean that the loss of well-being for low-income households was more limited than for higher-income ones. Notably, low-income counties suffered from larger job losses. Rather, they suggest that low-income households had less latitude to adjust their spending, as the higher share of necessities in their consumption basket would make it difficult to cut spending by more even in the face of higher job losses.

Differences in Consumer Spending by Race

We now turn to differences in aggregate consumer spending by race. As we see in the chart below, there is a gap between MM and MNM counties, with MNM counties experiencing smaller declines than MM counties after the pandemic begins. The gap arises at the beginning of the pandemic, but essentially disappears by the late summer of 2020. This disparity between both groups of counties remains small throughout, and we see the gap closing completely more than once in 2021.

This analysis may mask the differential experience of smaller versus larger businesses since the consumer spending data we analyze here capture spending at both small and large businesses. Stayed tuned for parallel analysis in an upcoming blog. Coupled with the analysis in this post, that forthcoming analysis will allow us to distinguish between spending at small versus large businesses and unearth how these differed across race and income.

Conclusion

In this post, we have looked at the trends in spending at all businesses as captured by credit and debit card transactions during the course of the pandemic. Although all counties saw an immediate decline in consumer spending as the pandemic hit, differences have emerged in both the magnitude and subsequent recovery patterns. The analysis suggests that low-income counties experienced a shallower recession and a more robust recovery in consumption than higher-income counties did. This may be a consequence of government policies supporting income, as well as of individuals in lower-income counties having lower consumption of the kinds of discretionary purchases—restaurant meals, travel, and entertainment—that were hardest hit by the pandemic. However, heterogeneity in economic activity by race is both more limited and more nuanced. We will revisit this topic on heterogeneity in economic activity in several weeks in a forthcoming post on small business experience, where we will investigate whether activity at small businesses varied across counties that differed by race and income. In the companion post in this series, we will focus on goods and services that were cut back the most during the pandemic and investigate which households cut spending on these goods the most.

Ruchi Avtar is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Maxim Pinkovskiy is a senior economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Maxim Pinkovskiy is a senior economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Giorgio Topa is a vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

Giorgio Topa is a vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Ruchi Avtar, Rajashri Chakrabarti, Maxim Pinkovskiy, and Giorgio Topa, “Racial and Income Gaps in Consumer Spending following COVID-19,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 12, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/05/racial-and-income-gaps-in-consumer-spending-following-covid-19.html.

Related Reading

Who’s Ready to Spend? Constrained Consumption across the Income Distribution

Discretionary and Nondiscretionary Services Expenditures during the COVID-19 Recession

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics