At the outbreak of the pandemic, in March 2020, the Federal Reserve implemented a suite of facilities, including two associated with international dollar liquidity—the central bank swap lines and the Foreign International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) repo facility—to provide dollar liquidity. This post discusses recent evidence showing the contributions of these facilities to financial and economic stability, highlighting evidence from recent research by Goldberg and Ravazzolo (December 2021).

International Dollar Liquidity during the Pandemic

Extreme uncertainty and expectations of a severe global economic downturn in March 2020 led to simultaneous supply and demand shocks in global U.S. dollar funding markets. Greater risk aversion and a desire to hold precautionary cash balances led banks and nonbank financial institutions to reduce dollar intermediation in funding markets. Corporations, faced with reduced access to U.S. dollar funding markets, drew down their committed credit lines with banks. As some banks, including the U.S.-hosted branches of foreign banking organizations, had large liquidity risk exposures through this channel, the resulting increases in bank loans contributed to new dollar funding needs (Cetorelli, Goldberg, and Ravazzolo [June 2020]). Such needs were met, in part, with bank branches either retaining dollars that might have flowed to their parents or the parents adjusting their balance sheets to obtain needed dollars. In addition, some non-U.S. banks and corporations sought to build extra liquid dollar balances, plugged holes in their balance sheets due to currency mismatch, or increased hedging demand for U.S. dollars.

The Cost of Dollar Liquidity

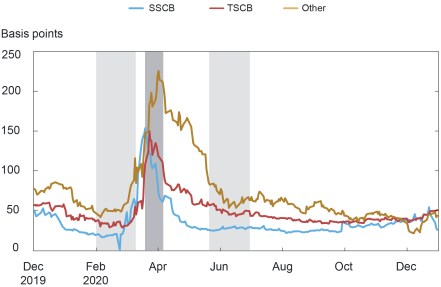

During the very early period of the pandemic, Cetorelli, Goldberg, and Ravazzolo (May 2020) show that the settlement of dollars demanded at the Fed’s standing swap lines operations calmed funding strains, even more than the announcement of facilities. Further, Goldberg and Ravazzolo (2021) show that country access to the Fed’s international dollar liquidity facilities is associated with reduced costs of borrowing dollars locally in the foreign exchange (FX) swap market, initially only for countries of central banks with access to standing or temporary swap lines (SSCBs or TSCBs) and later also for countries without swap lines but with access to the FIMA repo facility (Others). They define three periods: an initial pre-pandemic period (typically starting in Dec 2019 and proceeding through early March 2020), then a period of heavy strains (typically March 19 through early April), followed by a period when some central banks without access to swap lines established their access to the FIMA repo facility by setting relevant accounts (typically mid-late April/May through June 2020). The specific dates of each period vary according to the specific data analyzed.

The FX swap basis spreads (the basis) indicate the marginal cost of obtaining dollar funding offshore relative to borrowing in onshore funding markets. The chart below shows the average basis for three groups of countries: those that obtained dollars from SSCB or TSCB operations or the FIMA repo facility. The average basis increased in the initial stress period (dark grey area) compared to the pre-pandemic period. The currencies of countries with access to swap lines stabilized quicker than those without (that is, the “Other” countries), although relatively less liquid trading conditions in “Other” countries may have initially amplified strains in their local dollar funding markets. After the activation of the FIMA repo accounts, currencies of “Other” countries had large declines in dollar funding strains, despite minimal aggregate usage of the FIMA repo facility in the spring of 2020 (right light grey area in the chart). While dollar funding conditions for SSCB countries returned to pre-pandemic levels, the experiences of TSCB and “Other” countries remained more differentiated. For all countries with access to swap lines or the FIMA repo facility, analytics show there was also a reduced sensitivity of the dollar funding strains to changes in risk sentiment.

FX Swap Basis Spreads Stabilize following Fed Actions

Sources: Bloomberg; authors’ calculations.

Notes: Data are as of 11 a.m., London time, and are based on overnight unsecured funding rates (OIS) along with bilateral spot and forward exchange rates with three-month tenors. A positive number reflects a premium to borrow or hedge U.S. dollars. SSCB and TSCB refer to countries of central banks with access to standing and temporary swap lines, respectively. “Other” refers to countries without swap lines but with FIMA repo facility access. Lines represent group simple averages of the basis spreads over currencies in SSCB, TSCB and Other countries, and shadow area periods are defined in Goldberg and Ravazzolo (December 2021).

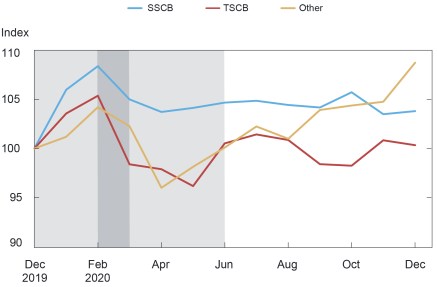

The Quantity of Dollar Liquidity

Some countries liquidated stocks of foreign currency reserves and reduced U.S. Treasury holdings to raise dollar liquidity to build precautionary buffers, to support the dollar funding needs of local institutions, and for central bank official interventions in foreign exchange markets. We find that official reserve balances of countries without swap lines declined on average in the Spring of 2020 and show that these balances reverted back only after the establishment of FIMA repo facility access. Foreign entities, including private investors, from countries with access only to temporary facilities (the TSCB or the FIMA repo) on average reduced U.S. Treasury holdings early in the pandemic (next chart, dark grey band), with further reductions occurring in April and May 2020 for countries without swap lines.

U.S. Treasury Holdings of Foreign Countries

Sources: U.S. Treasury Department; authors’ calculations.

Notes: SSCB and TSCB refer to countries of central banks with access to standing and temporary swap lines, respectively. “Other” refers to countries without swap lines but with FIMA repo facility access. Monthly series are indexed to 100 using December 2019 values. Shaded areas are explained in the text.

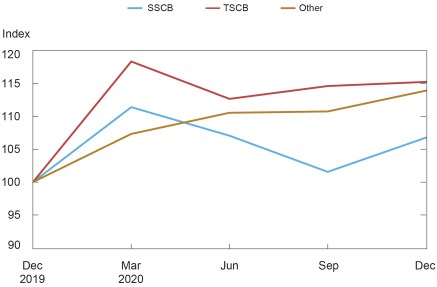

Goldberg and Ravazzolo (December 2021) show that the international swap lines and the FIMA repo facility potentially supported credit provision in the United States and abroad. Using Bank for International Settlements International Banking Statistics, they analyze changes in claims, which are associated with assets and provisions for funding, and in liabilities, associated with receipts and uses of funding, of foreign banking systems. The results confirm that cross-border banking flows did not collapse in the aftermath of the pandemic shock, a sharp departure from patterns in the global financial crisis. Additionally, banking systems with access to standing and temporary swap lines continued to provide substantial credit to both bank and nonbank borrowers in countries external to their bank locations during the early part of the pandemic and at a higher rate than provided by banks in countries without access to swap lines.

The next chart shows the cross-border banking liabilities of the specific countries in the respective groupings, with increased liabilities in the chart indicating greater credit provision by banks. Credit provision went mostly to bank borrowers in countries with access to swap lines, particularly those with access to the TSCB. There appears to be a reduction in credit provision in countries with swap lines during the April to June 2020 period, although, on net, their bank liabilities remained higher than their pre-pandemic levels. Interestingly, the gap between countries with SSCB or TSCB access and “Other” countries closed in the later period, and after the FIMA repo accounts were established, as the surge of liabilities of banks in SSCB countries somewhat reverted and banks in “Other” countries had further increases in inflows.

Cross-Border Liabilities (Non-U.S. Bank Sector)

Sources: Bank for International Settlements, authors’ calculations.

Notes: SSCB and TSCB refer to countries of central banks with access to standing and temporary swap lines, respectively. “Other” refers to countries without swap lines but with FIMA repo facility access. Quarterly series are indexed to 100 using 2019:Q4 values.

Bond fund flows were stable across countries and quickly reverted back or expanded beyond pre-pandemic levels by June 2020. In contrast, global equity portfolio inflows for all countries sharply contracted in March 2020 and remained depressed through summer 2020.

Summing Up

After the outbreak of the pandemic crisis, the Fed’s international dollar facilities helped stabilize market conditions and increased credit provision globally in a very short time, particularly in countries with access to the Fed’s standing swap lines. When facilities were in place and accessible as backstops, they generally helped reduce the sensitivity to risk of offshore dollar funding. Access to the different types of Fed international dollar facilities also mattered for the speed and degree of normalization of conditions in offshore dollar funding markets. Finally, continuation of cross-border lending through banks to countries appears to be associated with access to the Fed facilities.

Linda Goldberg is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Fabiola Ravazzolo is an officer in the Bank’s Markets Group.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics