Editor’s note: Since this post was first published, in a few instances we have updated inexact descriptions to clarify the demographic discussion. These updates did not affect our findings. (July 13, 3:54pm)

One of the two monetary policy goals of the Federal Reserve System— one-half of our dual mandate—is to aim for “maximum employment.” However, labor market outcomes are not monolithic, and different demographic and economic groups experience different labor market outcomes. In this post, we analyze heterogeneity in employment rates by race and ethnicity, focusing on the COVID-19 recession of March-April 2020 and its aftermath. We find that the demographic employment gaps temporarily increased during the onset of the pandemic but narrowed back by spring 2022 to close to where they were in 2019. In the second post of this series, we will focus on heterogeneity in inflation rates, the second part of our dual mandate.

We focus on the Employment to Population Ratio (EPOP) for prime-aged workers, as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as a measure of the state of the labor market for a given group. This is the ratio of the number of people aged 25 to 54 in each group who are employed (including self-employed) to the total number of people in that age bracket in that group. An alternative measure could be the unemployment rate; however, it captures only people who are not employed but are looking for work and misses people who currently have given up looking for work but may return to work when economic conditions improve. An extensive literature suggests that these people are an important part of labor market dynamics. In contrast, EPOP accounts for people dropping out of and then returning to the labor force for economic reasons. A possible problem with EPOP computed for the entire adult population—as well as with other labor market measures—could be if, over time, people spend more time getting an education or retire early, or if the age composition of the population changes. Therefore, we consider EPOP only for prime aged workers—those between 25 and 54—who typically have completed their education and would work under ordinary circumstances. Indeed, this age group tends to be strongly connected to employment; in February 2020 on the eve of the arrival of COVID, this group had an EPOP ratio of more than 80 percent.

The chart below presents the path of the EPOP ratio for the average American. We see that at the beginning of the COVID-19 recession in March 2020, employment rates plummeted—out of every eight prime-aged workers employed in February 2020 only seven were still employed in April. However, employment rates rebounded sharply after the end of the initial wave of COVID and the associated lockdowns, recovering more than 6 out of every 10 lost jobs among prime-aged workers by the end of the year. By May 2022, employment rates for prime-aged workers on average have returned to their pre-COVID levels of roughly 80 percent.

Employment to Population Ratio Rebounds to Pre-Pandemic Levels

Notes: Not seasonally adjusted. Population age 25-54. The shaded area indicates a period designated a recession by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

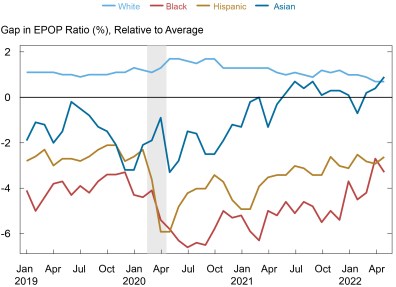

Turning to demographic heterogeneity in employment rates, the chart below presents gaps between the employment rates for white, Black, Hispanic and Asian Americans relative to the average employment rate we saw in the previous chart. As these are deviations from the average, if every demographic group experienced the same employment dynamics as did the average, we would expect to see the trends in the gaps to look like horizontal lines, rather than to see pronounced downward spikes during the COVID-19 recession. Any further downward spikes that we observe would arise from some groups suffering a more severe recession than the national average.

COVID-19 Recession Widened Demographic Employment Gaps Severely but Temporarily

Notes: Not seasonally adjusted. Demographic categories not mutually exclusive. Population age 25-54. The shaded area indicates a period designated a recession by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

We observe that the COVID-19 recession affected the employment rate gaps for Black and Hispanic Americans relative to the national average. In February 2020, right before the arrival of COVID, Black and Hispanic Americans were, respectively, around 4 percent and 2 percent less likely to be employed than the average American (once again, on a base of an 80 percent employment rate for prime age workers at the time). At the onset of the pandemic, Black and Hispanic Americans were disproportionately likely to lose their jobs, which expanded these gaps to 6 percent or more for both Black and Hispanic Americans around the trough of the COVID-19 recession. However, in the subsequent months, these gaps narrowed until by May 2022 the Hispanic gap was nearly back to its pre-pandemic levels, while the Black American gap was even smaller than it was right before the pandemic. In May 2022, prime-age Black Americans were 3.3 percentage points less likely to be employed than white Americans, while in February 2020 they were 4.4 percentage points less likely to be employed. Similarly, the Hispanic-white employment gap stood at 2.6 percentage points in May 2022 compared to 2.3 percentage points on the eve of the pandemic.

Thus, both in the aggregate and looking individually by demographic groups, the picture of the U.S. labor market provides a case for cautious optimism. Unlike the aftermath of the Great Recession, when employment rates took nearly a decade to return to their pre-recession peak, both on average and for Black and Hispanic Americans, employment rates are nearly back to their pre-COVID levels within two years of the start of the pandemic. The relative resilience of the labor market after COVID testifies to the different impacts of major but temporary external shocks relative to failures in financial markets that generate a protracted drag on economic activity.

It is interesting and important to ask how the demographic gaps in employment rates may evolve going forward. Several studies suggest that increases in interest rates have heterogeneous effects on the employment rates of different demographic groups, with employment rates of Black Americans falling more than employment rates of white Americans, especially in labor markets that are already tight. Therefore, the recent rise in interest rates may undo some of the narrowing that we have observed in this post. However, it is important to note that the current interest rate increase is coming at a time when demographic gaps in employment rates are at some of their lowest levels in decades. We will continue monitoring labor market disparities as the as the economy and policies continue to evolve.

Ruchi Avtar is a research analyst in Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is the head of Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Maxim Pinkovskiy is an economic research advisor on Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Ruchi Avtar, Rajashri Chakrabarti, and Maxim Pinkovskiy, “How Equitable Has the COVID Labor Market Recovery Been?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, June 30, 2022, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/06/how-equitable-has-the-covid-labor-market-recovery-been/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

This article doesn’t discuss reasons which contributed to encouraging various peoples to not return to the labor market: eviction bans, rent assistance, stimulus payments. There are some groups who want to “do for themselves” rather than taking the free hand out.