During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Reserve placed restrictions on large banks’ dividends and share repurchases. These restrictions were intended to enhance banks’ resiliency by bolstering their capital in light of the very uncertain economic environment and concerns that banks might face very large losses should bad-case scenarios come to pass. When it became clear that the outlook had improved and that the losses banks experienced were unlikely to threaten their stability, the Federal Reserve removed these restrictions. In this post, we look at what happened to large banks’ dividends and share repurchases during and after the pandemic-era restrictions, tracking these shareholder payouts relative to bank profits to understand how these payments impacted large banks’ capital during this period.

Shareholder Payouts and Bank Capital

Since the global financial crisis, large banks have significantly increased their capital resources. Both regulatory capital ratios and capital levels—the dollar amount of capital on large banks’ balance sheets—have increased meaningfully since the early 2010s. Capital, particularly common equity, is the first line of defense against losses that could threaten a bank’s solvency and the higher capital held by large banks has increased the sector’s ability to weather significant shocks.

Banks can increase capital levels in two basic ways: by issuing more new equity in public markets than the amount they repurchase from existing shareholders or by earning more income than the dividends they pay. Since large new common equity issuance is relatively rare, the key relationship is between bank earnings and the combination of dividends and share repurchases, or shareholder payouts. In that case, when net income exceeds shareholder payouts, equity capital increases.

Bank Shareholder Payouts during the Pandemic

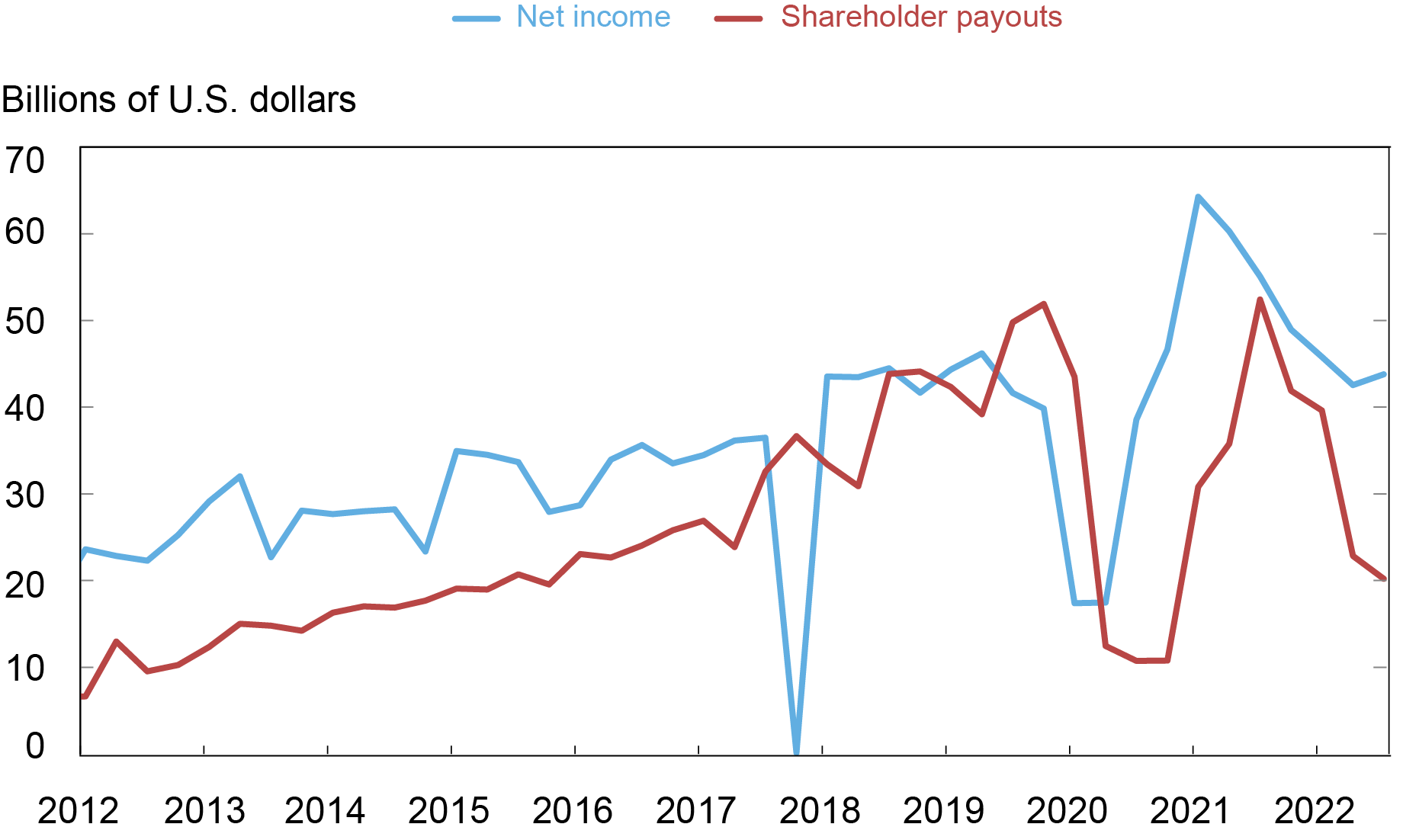

The chart below shows the relationship between after-tax net income and shareholder payouts between 2012 and the third quarter of 2022 for a set of large bank holding companies subject to the Federal Reserve’s payout restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The restrictions prohibited share repurchases and capped dividends at their second quarter of 2020 levels. These formal restrictions followed a coordinated suspension of share repurchases by several large banks in March of 2020. Banks were allowed to resume repurchases at the start of 2021, as long as the sum of repurchases and dividends did not exceed net income over the past year. Starting in the third quarter of 2021, after the 2021 stress tests indicated that all large banks would remain above minimum capital requirements, these special pandemic-related restrictions were lifted. While these restrictions applied to thirty-four bank holding companies in total, to create a time-consistent sample, the chart includes data for the twenty-one U.S.-owned bank holding companies with data available since 2012.

Net Income and Shareholder Payouts

Twenty-one Large Bank Holding Companies, 2012:Q1-2022:Q3

Note: For a time-consistent sample, the data cover twenty-one of the thirty-four bank holding companies subject to the Federal Reserve’s shareholder payout restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aggregate net income (the blue line in the chart) increased steadily for these banks in the years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. (The sharp drop in net income at the end of 2017 reflects an accounting change that caused many banks to recognize one-time losses related to their deferred tax assets.) Shareholder payouts (the red line) also increased over these years, though at faster pace than net income. In 2012, shareholder payouts were significantly less than net income, meaning that these banks were accumulating capital via retained earnings. But by the second half of 2018 through the onset of the pandemic, payouts equaled or exceeded net income, meaning the large banks were no longer increasing the level of capital on average.

With the onset of the pandemic, both net income and shareholder payouts dropped sharply. As the chart illustrates, net income for these banks dropped by more than 50 percent in the first quarter of 2020, due mainly to large provisions for loan losses. Shareholder payouts also declined in that quarter, though by less than the drop in net income. Payouts dropped sharply the following quarter and remained low through the end of 2020, even as net income recovered to levels closer to those prevailing before the pandemic. Payouts peaked in the third quarter of 2021, when the Federal Reserve lifted restrictions, and have fallen since then, tracking a decline in net income over this period. As of the third quarter of 2022, shareholder payouts were significantly below the levels prior to the pandemic.

The Repurchases Cycle

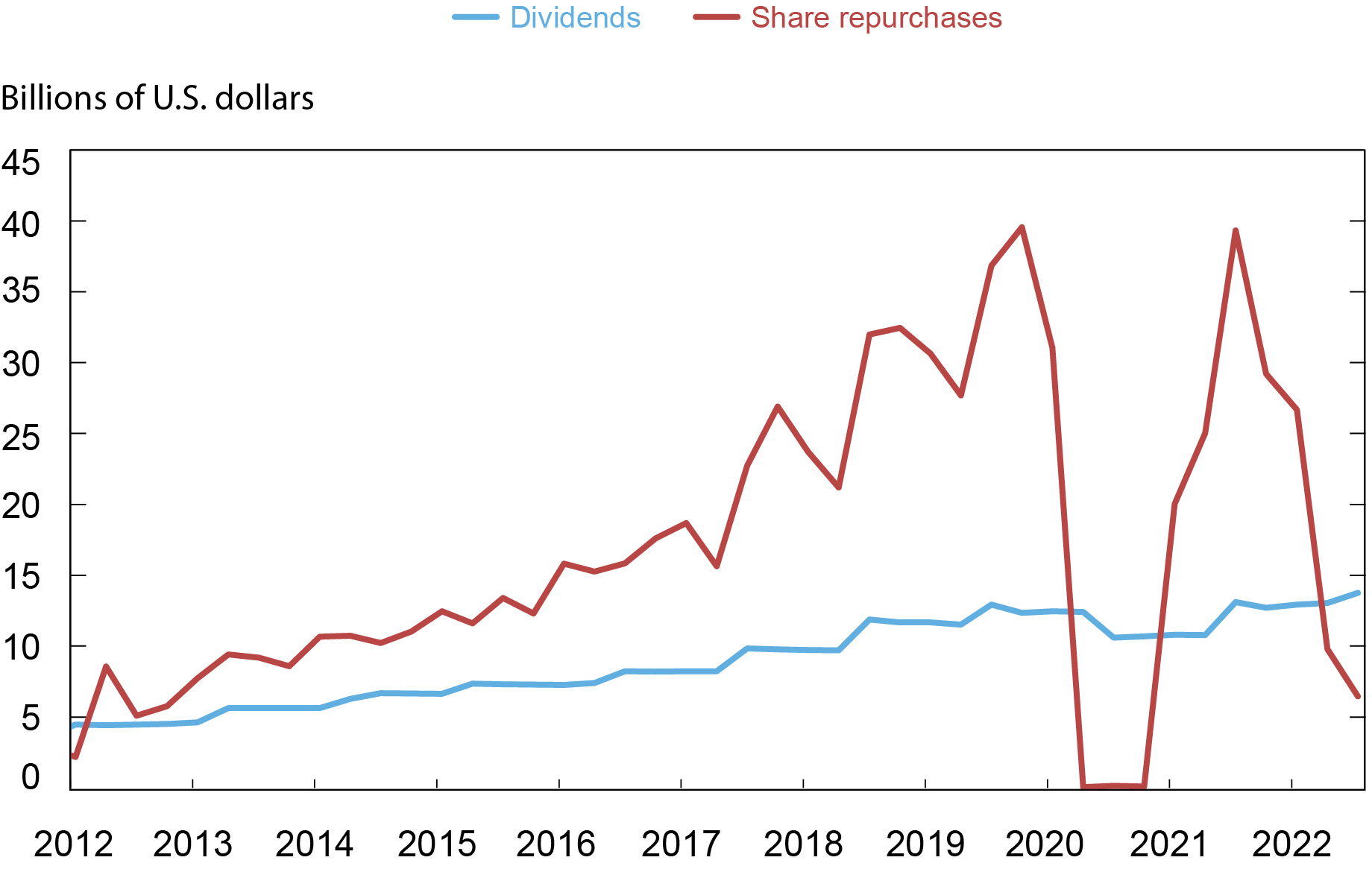

Nearly all of the movement in shareholder payouts since the pandemic is accounted for by changes in repurchases as the chart below illustrates. Both repurchases (the red line in the chart) and dividends (the blue line) increased in the years prior to the pandemic. While dividends increased by small but steady increments during this period, repurchases by these banks soared, rising from about $5 billion per quarter in early 2012 to nearly $40 billion per quarter at the end of 2019. Repurchases dropped to near zero in the second quarter of 2020, reflecting both the Federal Reserve’s restrictions and a separate suspension of repurchases by some bank holding companies, before rebounding when the Fed eased its restrictions at the start of 2021. Dividends also declined in mid-2020, but by a significantly smaller amount, returning to pre-pandemic levels when the Federal Reserve’s restrictions were removed in the third quarter of 2021.

Dividends and Share Repurchases

Twenty-one Large Bank Holding Companies, 2012:Q1-2022:Q3

Note: For a time-consistent sample, the data cover twenty-one of the thirty-four bank holding companies subject to the Federal Reserve’s shareholder payout restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The much greater volatility of repurchases relative to dividends reflects long-established patterns, not just in banking but broadly among publicly traded nonfinancial firms. Dividends are much less volatile than repurchases. Dividend changes are highly visible to market participants, with firms making public announcements when dividends are declared, and generally interpreted as signals of sustained increases (or decreases) in profitability. In contrast, repurchases are more discretionary; while firms announce their intention to repurchase shares, they are not bound to make all the repurchases they announce. Repurchases are used more intensively by nonfinancial firms with more variable incomes, as a way to flexibly manage payouts to shareholders.

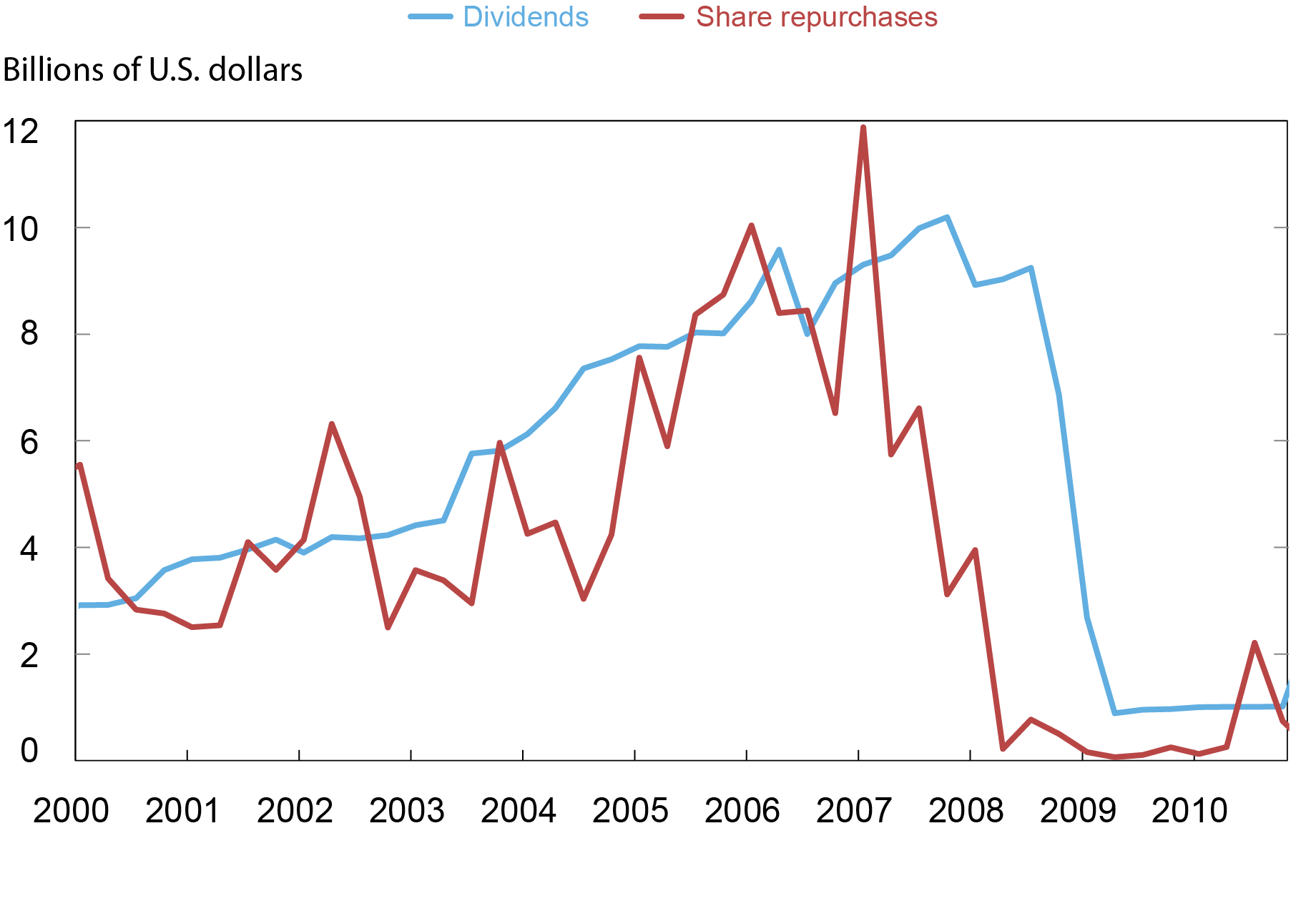

As with nonfinancial firms, large banks also have a history of using repurchases flexibly. For example, during the global financial crisis, large banks ceased repurchases almost entirely by mid-2008, nearly a year before dividends fell to similarly low levels. The chart below illustrates this behavior for the thirteen bank holding companies in our twenty-one-bank sample with data available in the pre-global-financial-crisis period. While stopping repurchases was an important step towards retaining capital during this turbulent period, repurchases represented only about half of overall shareholder payouts at that time, limiting the impact of cutting them back. Reflecting this experience, supervisors have encouraged greater use of more flexible repurchases to make it easier for banks to reduce distributions during periods of uncertainty, through programs such as the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR)—a development that has resulted in the very significant shift towards repurchases in the 2010s.

Dividends and Share Repurchases

Thirteen Large Bank Holding Companies, 2000:Q1-2010:Q4

Note: The chart illustrates trends for a smaller subset of bank holding companies subject to the Federal Reserve’s pandemic restrictions for which pre-global-financial-crisis data are available.

Payout Flexibility in Action

The repurchases cycle experienced during the pandemic era is a particularly striking example of this flexibility in action, in both directions. Not only did repurchases drop sharply in the early phase of the pandemic, but they also rebounded sharply when bank profits recovered, allowing a period of “catch up” for distributions that were held back in the very uncertain economic environment of 2020. The significant role of repurchases in overall shareholder payouts have allowed these payouts to track changes in profitability over time.

Beverly Hirtle is the director of research and head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sarah Zebar is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Beverly Hirtle and Sarah Zebar, “Bank Profits and Shareholder Payouts: The Repurchases Cycle,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, January 9, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/01/bank-profits-and-shareholder-payouts-the-repurchases-cycle/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

I understand clearly why banks might call share buybacks ‘shareholder payouts’ despite the fact that only benefactor of a share purchase is the share seller. All the other shareholders see no nominal return. Share buybacks paid for from net Income (and thus diverted away from becoming capital retention) are purely for the benefit of the seller of stock and those whose metric of success is based on the price of the companies stock. In short .. the US would be better served retaining capital than projecting success via pumping stock prices. And the NY federal reserve would be better served not referring to such action as ‘shareholder payouts’.

Thank you for your article, but I don’t understand why Share Repurchases shoud be considered as a way to remunerate shareholders. With a buyback, a loss in value of the company is instantly determined; the new value is diluted over a smaller number of shares, with no theoretical impact on the unit value of the share after the buyback. Remuneration of shareholders through a buyback with cancellation of shares is therefore illusory. Any price effect specifically due to the transaction, due to a possible positive market reaction right from the announcement and then following the buyback, does not have an economic justification in relation to an increase in the intrinsic value of the equity, therefore, as such, there are no reasons why it can be considered for the benefit of the shareholder. Best regards