Editor’s note: Since this post was first published, the y-axis label on the first chart has been corrected to read “Billions.” January 18, 12:30 pm

The Federal Reserve’s primary credit program—offered through its “discount window” (DW)—provides temporary short-term funding to fundamentally sound banks. Historically, loan activity has been low during normal times due to a variety of factors, including the DW’s status as a back-up source of liquidity with a relatively punitive interest rate, the stigma attached to DW borrowing from the central bank, and, since 2008, elevated levels of reserves in the banking system. However, beginning in 2022, DW borrowing under the primary credit program increased notably in comparison to past years. In this post, we examine the factors that may have contributed to this recent trend.

Recent Rise in Discount Window Borrowing

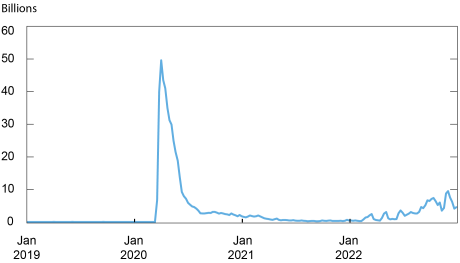

Following the onset of the COVID pandemic in early 2020, DW primary credit borrowing surged from near-zero levels to a peak balance of almost $50 billion in early April of that year, before subsiding quickly (see chart below). (Note that the DW also offers secondary and seasonal credit, less-utilized programs that did not experience a surge in 2020.) The increase in borrowing was broad-based as both small and large banks used the DW. The domestic Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs), in particular, pre-announced their intention to borrow at the DW to encourage its use during the pandemic. Although they didn’t have a need to borrow given their ample reserve balances, each G-SIB took out token loans as large as $5 billion for ninety days.

Most of the G-SIBs borrowed just once near the start of the pandemic, and as their loans matured, the loan balances fell back down. Other banks followed suit and DW loan balances returned to minimal levels in subsequent months. However, in 2022, there was a renewed increase in balances, approaching $9 billion in November, as seen in the chart below. While low relative to the early days of the pandemic, recent DW loans are greater than in the years prior to the pandemic by several multiples. For example, the peak amount of DW loan balances in 2019 was $70 million.

Discount Window Loans Outstanding Were Low after the Pandemic but Have Increased Recently

Note: Values are weekly averages.

The rise in DW loan balances began in February of 2022, just before the Fed started to increase the target range for the federal funds rates. Although some observers initially noted a pattern of increased borrowing around FOMC meetings, this pattern is no longer observed.

What Accounts for the Recent Trend in Discount Window Borrowing?

On March 15, 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, the Federal Reserve implemented two policy changes to make the DW primary credit program more attractive to utilize. First, the premium of the primary credit DW rate over the top end of the federal funds target range was reduced from 50 basis points to zero, ending the penalty cost of borrowing from the DW relative to market funding sources, or other alternatives such as the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs). Second, the maximum term of primary credit was extended from an overnight tenor—the typical limit—to ninety days, with the option to prepay at any time. These policy changes made DW borrowing more economical and flexible, and they remain in effect today.

The notable decline in the total level of reserves in the banking system this year may have been an important factor for the rise in DW borrowing. Indeed, as the Fed has gradually shrunk its balance sheet, the cash balances of smaller institutions, particularly those with total assets less than $10 billion, have in aggregate declined sharply relative to their asset size, reducing their liquidity positions (see table below).

Cash Balances of Small Banks Have Declined Notably Recently

Cash to total assets ratio by bank asset size, percent

| Asset Range | 12/31/21 | 3/31/22 | 6/30/22 | 9/30/22 |

| ≤ $3 billion | 13.4 | 8.7 | 6.8 | 6.0 |

| $3 billion – $10 billion | 13.6 | 9.0 | 7.3 | 7.3 |

| $10 billion – $50 billion | 16.4 | 17.2 | 16.3 | 13.7 |

| > $50 billion | 17.2 | 16.7 | 14.5 | 14.7 |

| Total | 16.5 | 15.3 | 13.3 | 13.1 |

Additionally, smaller banks are generally more willing to come to the DW than their larger counterparts, as they are usually not publicly traded companies and are less subject to public scrutiny. As shown in the table below, banks smaller than $3 billion in assets on average visited the DW twice as much as other banks in 2019, just prior to the pandemic.

Small Banks Have Used the Discount Window More than Larger Banks

| Asset Range | Number of Banks | Average Days of Borrowing |

| ≤ $3 billion | 189 | 4 |

| $3 billion – $10 billion | 29 | 2 |

| $10 billion – $50 billion | 17 | 2 |

| > $50 billion | 5 | 2 |

| Total | 240 | 3 |

Note: Average days of borrowing is defined as the total number of days that each bank borrowed for non-testing purposes aggregated across all banks, then divided by the number of distinct banks that borrowed.

Prior to the pandemic, small banks came to the DW on an ad hoc basis when they had a need for overnight borrowing to meet an unanticipated funding shortfall. When anticipating a more durable need for short-term funds, small banks typically borrowed for term from the FHLBs. Due to their limited sophistication, small banks are not active borrowers in the fed funds market.

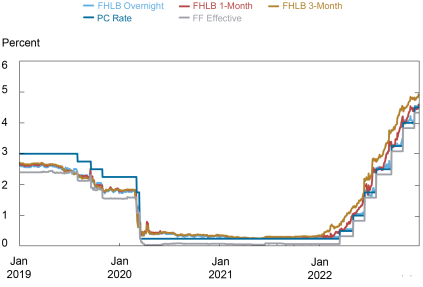

So far in 2022, small banks generally appear to have continued to rely on FHLB borrowing to meet funding needs, as their FHLB borrowing has risen by approximately 20 percent to $183 billion relative to the prior year, according to the most recently available Call Report data. But with the elimination of the DW primary credit rate penalty and the availability of term DW loans, it appears that DW credit has become more competitive with FHLB term advances. This is particularly true for longer dated maturities of sixteen to ninety days that comprise close to half of the DW primary credit loans outstanding in recent months, according to Federal Reserve data. As the chart below shows, the three-month FHLB advance rate has been as much as 130 basis points higher than the DW primary credit rate, and the one-month FHLB advance rate as much as 90 basis points higher than the DW rate. (Note that the DW rate is the same for both overnight and term maturities.) By comparison, prior to the pandemic, FHLB rates were below the DW rate, and in 2021 they were at about the same level as the DW rate.

FHLB Rates Recently Climbed above the Discount Window Rate

In addition to their relatively higher rates, regulatory factors may have created a disincentive for small banks to take out FHLB advances. In particular, a bank must have positive tangible capital to qualify for FHLB loans unless its federal banking agency or insurer requests in writing that the advance be made. As interest rates increased in 2022, banks experienced losses on their purchased securities, which is reflected in a declining ratio of tangible equity capital to total assets. According to Call Report data, this ratio declined between 2021:Q4 and 2022:Q3, with smaller banks suffering bigger declines. However, so far only a small subset of banks are experiencing negative tangible capital, and these banks account for a negligible share of DW borrowing.

Final Words

The recent increase in primary credit borrowing from the DW may appear to be somewhat surprising, given the low and declining usage of the DW prior to the pandemic. We suggest that the lower rates and longer terms available under the primary credit program, combined with declining reserve balances in the banking system, have all contributed to this trend. It will be interesting to see whether this recent pattern in DW borrowing continues into the future or whether there is a return to the historical patten of DW borrowing.

Helene Lee is a capital markets trading principal in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Asani Sarkar is a financial research advisor in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Helene Lee and Asani Sarkar, “The Recent Rise in Discount Window Borrowing,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, January 17, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/01/the-recent-rise-in-discount-window-borrowing/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics