Marco Del Negro and Mary Tao

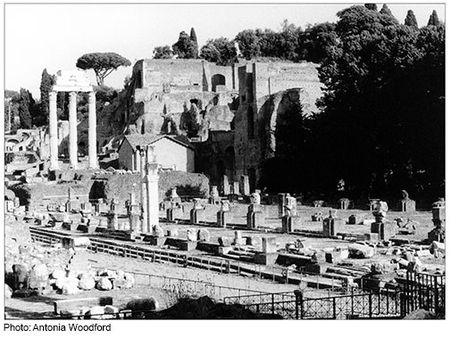

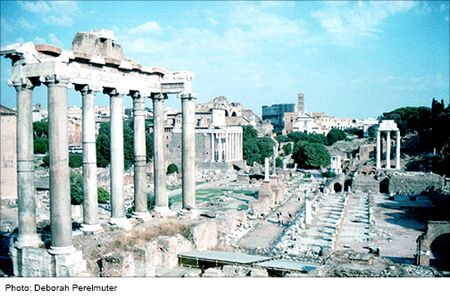

The Forum. This is where finance happened

in ancient Rome. According to the historian Jean Andreau (“Banking and Business in the Roman World”), both run-of-the-mill banking and high finance took place in the Forum. The former was performed by money lenders (in Latin, argentarii), who were mostly plebeians. The latter, as far as we know, was almost exclusively run by and for the patrician classes: senators and knights (equites).

Money lenders were a professional group (many of them were former slaves).

Taking deposits, making loans, and assaying and changing money (which was then

made of precious metals—gold, silver, and bronze—in different denominations) was how they made their living. Those patricians who were involved in high finance, however, often had a patrimony (land, real estate, slaves) and an income they could live off. Yet they sought to increase their wealth by lending both their money and other patricians’ money. To lend money for interest in Latin is called faenerare; hence, these people were called faeneratores (see also Koenraad

Verboven, “Faeneratores, Negotiatores and Financial

Intermediation in the Roman World”). They were “specialized businessmen who spent all their

time in the forum” (Andreau, p. 15), and who hung around the Janus

medius, a

vaulted passageway in the Forum: “Both creditors and lenders could be found

there—that is to say both passive investors seeking to place their money and

also intermediaries arranging credit, who were experts at investing money” (Andreau,

p. 16). To quote Cicero (De

Officiis, Book II):

“But this whole subject of acquiring money, investing money . . . is more profitably

discussed by certain worthy gentlemen at the Exchange [ad Janum medium] than could be done by any philosophers of any school.”

Just like with FICO scores today, creditors would share information about delinquent

debtors and post it on a column—the Columna

Maenia.

Run-of-the-mill banking was regulated in ancient Rome, and argentarii needed to maintain accounts of their transactions. For Latin jurists, “what

characterized a bank [argentaria] was the twofold service that it provided: receiving deposits and advancing credit” (Andreau, p. 39). Some deposits were just for safekeeping and yielded no interest (vacua pecunia), while others did earn interest (creditum). The latter could be invested, but not the former. However, most of the loans advanced by the argentarii were apparently short term and local. In essence, the argentarii were your neighborhood bank—that is, banking for the average Joe (or the average Caius).

Aristocratic finance—the faeneratores—was quite a different business, a sort of proto-“shadow banking system.” Elite financiers weren’t

subject to any special regulations. They would invest in far-flung places,

especially the provinces, and would have intermediaries (societas danistaria) making sure their loans produced a good

return. Sometimes they would act as private wealth managers (procuratores) for other patricians who didn’t want or didn’t know how to invest their money (unlike in the Middle Ages, lending with interest was not taboo in Rome, but spending all the time in the Forum was not considered very classy for a senator). Elite financiers had political power and, throughout Roman history, they would exercise it.

How much money was going through a faenerator’s

hands? Well, we know that one fellow, Q. Considius, probably a senator, held 15

million sesterces worth of debt claims. How much is that? The annual pay of a soldier in those days was about 9 aurei (see M.E.K. Thornton), and 1 aureus was worth 100 sesterces. With that money, Q. Considius could therefore have raised an army about the size of Slovakia’s. What happened if the lenders needed their money right away? Basically, there was something like a secondary market for debt: “He [the creditor] would sell on his debt-claims either to the intermediary who had ceded them to him or to some other intermediary, and the intermediary would then cede them to someone else. The mechanism seized up as soon as a liquidity crisis or a debt crisis developed” (Andreau, p. 18). But this—liquidity crises in the Roman world—is a topic for a future post.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Marco Del Negro is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group

of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Mary Tao is a research librarian in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Very interesting subject. Little or nothing pertaining to human nature occurs in the modern world that did not occur in the ancient one.