Health is an integral part of well-being. The United Nations Human Development Index uses life expectancy (together with GDP per capita and literacy) as one of three key indicators of human welfare across the world. In this post, I discuss the state of life expectancy inequality in the United States and examine some of the underlying factors in its evolution over the past several decades.

I will describe evidence in the health literature that first, inequality in life expectancy in the United States is increasing, and second, that life expectancy has become increasingly correlated with income. However, I will also argue that the mechanism at work is more complicated than higher income pushing up life expectancy. In particular, I will cite evidence that indicators of health care access do not correlate strongly with life expectancy among lower-income individuals. Instead, I will argue that shifts in the incidence of unhealthy behaviors explain much of the increase in life expectancy inequality. Specifically, I will show that the changing distribution of smoking across the income spectrum explains the strengthening of the relationship between life expectancy and income.

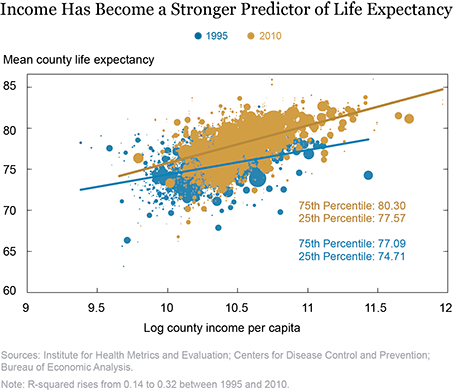

The chart below plots estimates of average life expectancy by county (from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, IHME) against log county income per capita from the BEA for 1995 (in blue) and 2010 (orange). Each dot represents a county, and the size of the dot is proportional to the county’s population. We see that over these fifteen years, life expectancy across U.S. counties has increased markedly—the 25th percentile of the 2010 population-weighted county life expectancy distribution is above the 75th percentile of the 1995 one. However, we also see that the 2010 distribution is more unequal than the 1995 distribution: Many counties enjoy much higher life expectancy than the mean, but a swath of counties—the points that still overlap with the 1995 life expectancy distribution—are falling behind. The interquartile range (the difference between the 75th and 25th percentiles, also a measure of variability of the distribution) grew from 2.38 years in 1995 to 2.73 years in 2010.

Most strikingly, we see that county life expectancy is much more closely related to county personal income in 2010 than it was in 1995. The blue and orange lines through the clouds of points show the lines of best fit between county life expectancy and log county income in 1995 and 2010. It is immediately obvious that the orange line is steeper than the blue line; life expectancy is more correlated with income in 2010 than it was in 1995. A 10 percent increase in county income was associated with an increase in average life expectancy in 1995 of three and a half months—versus an increase of five and a half months in 2010. It is also obvious that the orange dots (for 2010) fall more tightly around the orange line than do the blue dots around the blue line. Log county income explained 14 percent of the overall variability in average life expectancy across counties in 1995, but by 2010, it explained nearly one-third of that variation.

Looking at the chart, one may be tempted to conclude that the correlation it plots is causal –having a high income is now more important to accessing quality medical care, which in turn prolongs life. However, the story is more complicated. In a landmark 2016 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Raj Chetty and his coauthors investigate the correlates of the life expectancy of the poor across U.S. commuting zones. They find that the biggest determinants of life expectancy among low-income individuals are behavioral variables, such as smoking, obesity, and exercise rates. Surprisingly, measures of access to health care, such as the fraction of poor people who have insurance, or the provision of preventive care, are not correlated with the life expectancy of the poor, and neither are measures of a county’s economic health, such as its unemployment rate.

An even starker illustration of the limits of health care goods as a means to a higher life expectancy comes from recent work by Chen, Persson, and Polyakova (2019), who investigate the mortality-to-income gradient in Sweden. Unlike the United States, Sweden has universal health insurance, guaranteeing access to a baseline level of health care services to everyone regardless of their income. However, Chen et al. (2019) show that although Swedish mortality (the probability of dying in the next year at age 59) is lower than U.S. mortality for both the rich and the poor, the slopes of the two gradients are similar. That is, moving up an extra percentile in the Swedish income distribution would yield a very similar mortality reduction as moving up a percentile in the U.S. income distribution. This suggests that access to care is not the issue, since Swedes’ access is generally unrelated to their incomes.

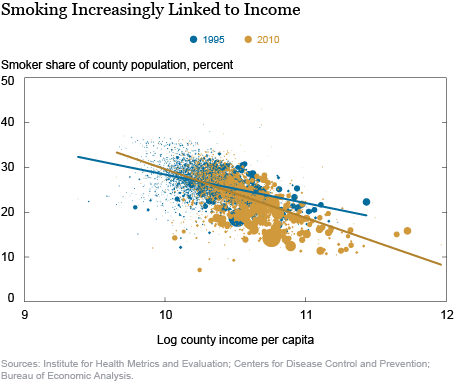

I conclude by showing that the strengthening of the relationship between county life expectancy and county income in the United States can be statistically explained by a third variable: the smoking rate. To do this, I use data on U.S. smoking prevalence by county from 1995 to 2010 from IHME. (This dataset runs from 1996 to 2012; I use the 1996 numbers for 1995 to match up with the county income dataset). The next chart shows that the relationship between smoking prevalence and income across U.S. counties has become stronger over time, mirroring the relationship between life expectancy and income. Not only did the smoking rate in the United States decline, on average, over these fifteen years, but it declined much more in high-income places than in low-income places.

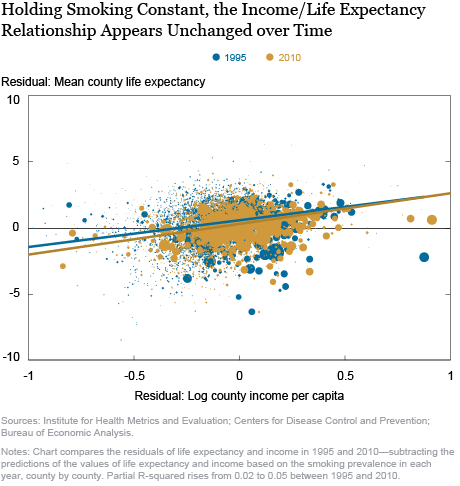

Finally, the last chart compares the residuals of life expectancy and income in 1995 and 2010—subtracting the predictions of the values of life expectancy and income based on the smoking prevalence in each year, county by county. Now, the two scatterplots are right on top of each other, and the lines of best fit through them—the relationships between life expectancy and income, controlling for smoking prevalence, in 1995 and in 2010—are nearly identical. In fact, controlling for the changes to smoking prevalence, income explains nearly the same (low) share of the cross-county variation in average life expectancy in 2010 as it did in 1995. The strengthening of the relationship between income and life expectancy that we observed before can be explained entirely by the intensification of the relationship between income and smoking prevalence.

While income now appears to be more salient to health outcomes than it has been in a generation, paradoxically, redistributing income and the health resources that it buys does not seem sufficient to improve health outcomes for individuals in the bottom of the life expectancy distribution. Instead, a more promising approach might center on reducing adverse health behaviors that used to be widespread but are now increasingly concentrated among the poor. Figuring out how to do this will be the key to reducing health inequality.

Maxim Pinkovskiy is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Maxim Pinkovskiy is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Maxim Pinkovskiy, “Does U.S. Health Inequality Reflect Income Inequality—or Something Else?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 15, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/10/does-us-health-inequality-reflect-income-inequalityor-something-else.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics