One of the most striking features of the labor market recovery following the pandemic recession has been the surge in quits from 2021 to mid-2023. This surge, often referred to as the Great Resignation, or the Great Reshuffle, was uncommonly large for an economic expansion. In this post, we call attention to a related labor market change that has not been previously highlighted—a persistent change in retirement expectations, with workers reporting much lower expectations of working full-time beyond ages 62 and 67. This decline is particularly notable for female workers and lower-income workers.

The Great Resignation

After an initial decline in the quit rate during the pandemic recession, which saw the unemployment rate climb to 14.8 percent in April 2020, the quit rate rose sharply in 2021 and remained high into early 2023. Estimates of the exact magnitude of the wave of resignations vary somewhat across data sources, with employer-provided data on quits from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) showing much greater increases in the quit rate than those computed using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS). However, there is broad agreement about the nature of the resignations: While there was a temporary surge in exits from the labor market, including an increase in early retirements, most of the quits represented switches to other (presumably better) jobs or transitions into self-employment. Furthermore, a large fraction of the workers who dropped out of the workforce, including many of those who retired early, subsequently reentered the labor market.

What caused this unusual surge in quits? Questions remain about their relative importance, but contributing factors proposed by economists include labor shortages and an increased confidence about finding new jobs; pandemic-related factors such as health concerns, lack of childcare, stimulus payments, and moratoria on mortgage, rent, and student loan payments; and changes in attitudes toward the purpose and desirability of work more generally. Some of the increase could also reflect pent-up resignations among those who postponed and held on to their jobs during the early days of the pandemic.

An important feature of the upswing in resignations is that it was particularly large for low-skilled workers. A shortage of workers, high job vacancy rates, and additional fiscal support in the form of economic impact payments and forbearance programs allowed workers to be choosier about their next job and to negotiate higher wage increases with current and new employers. After years of relative wage stagnation, greater worker power fueled an acceleration in wage growth, especially among low-skilled workers.

The Post-Pandemic Change in Retirement Expectations

In this post, we document an important related development not previously highlighted—a post-pandemic change in retirement expectations. Our analysis is based on data from the Survey of Consumer Expectations’ (SCE) triannual Labor Market Survey. Over its decade-long life the SCE, a foundational dataset of the Center for Microeconomic Data, has produced many valuable insights into consumer expectations about a wide range of economic behaviors and outcomes. The SCE is a nationally representative, internet-based survey of a rotating panel of approximately 1,300 household heads. Respondents participate in the panel for up to twelve months, with a roughly equal number rotating in and out of the panel each month. The SCE Labor Market Survey module, fielded triannually since March 2014, provides information on consumers’ experiences and expectations regarding the labor market. Our analysis in this post is based on two specific questions in the survey. The first asks respondents below age 62 “Thinking about work in general and not just your present job (if you currently work), what do you think is the percent chance that you will be working full-time after you reach age 62?”. A similar second question is then asked about working full-time beyond age 67, to those younger than age 67. The questions are similar to those asked in the University of Michigan’s Health and Retirement Study.

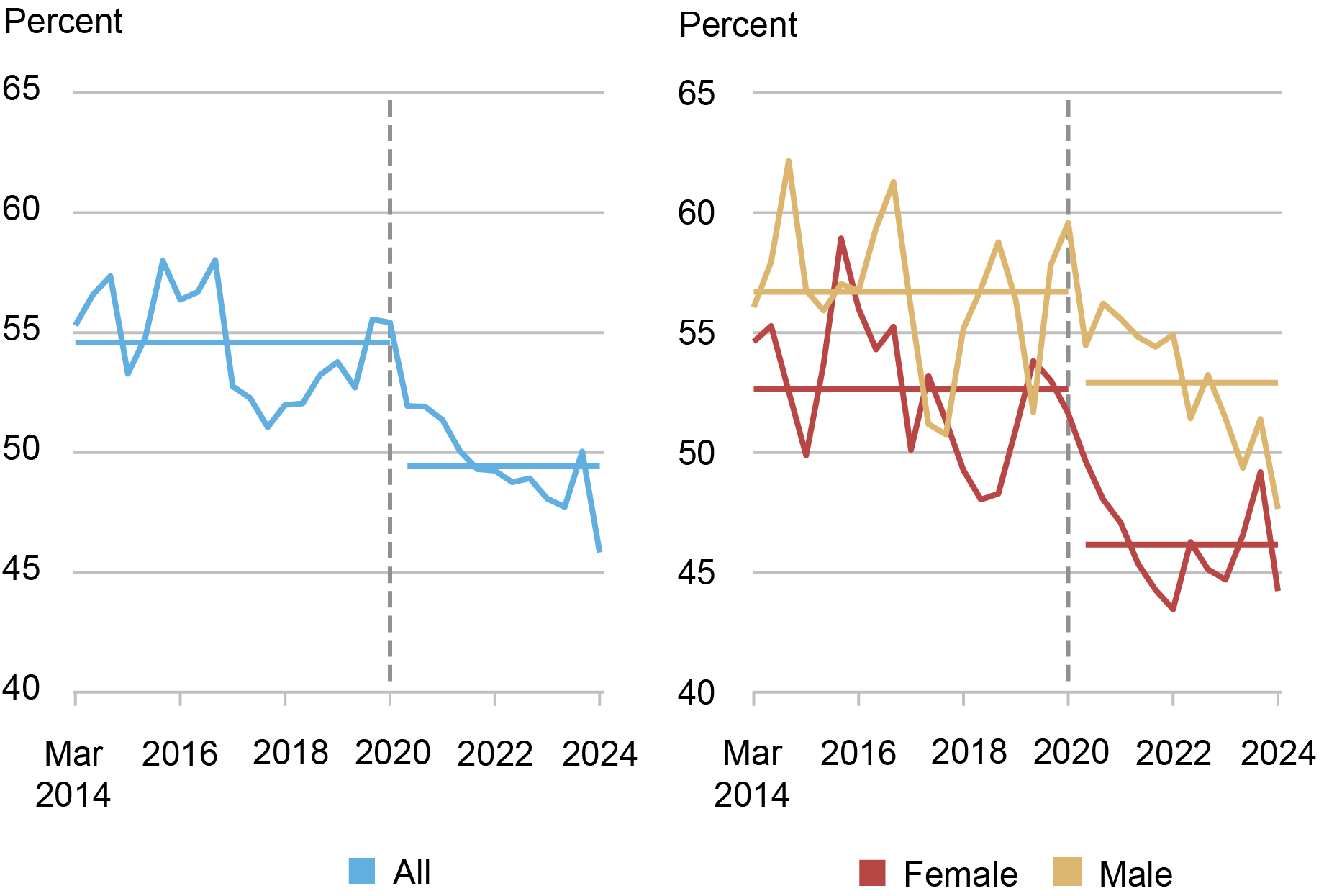

The left panel in the chart below displays retirement-age full-time employment expectations. Up to the eve of the pandemic, these expectations had been fairly stable. But starting in March 2020 they began a persistent decline, with the March 2024 reading of the average likelihood of working full-time beyond age 62 representing a new series low at 45.8 percent. While these expectations averaged 54.6 percent over the six years leading up to the pandemic, they have averaged 49.4 percent over the four years since, with the 5.2 percentage point decline equating to a 9.5 percent decrease in expected future full-time employment. The decline is broad-based across age, education, and income groups, with workers under age 45, without a college degree, and with annual household incomes below $60,000 showing slightly larger declines than their peers. However, the decline in the average probability of working full-time beyond age 62 is much more pronounced for female workers (6.5 percentage points) than for male workers (3.8 percentage points).

Average Likelihood of Working Full-Time Past 62

Notes: The vertical dashed lines indicate the start of the pandemic. Horizontal lines indicate pre- and post-pandemic means.

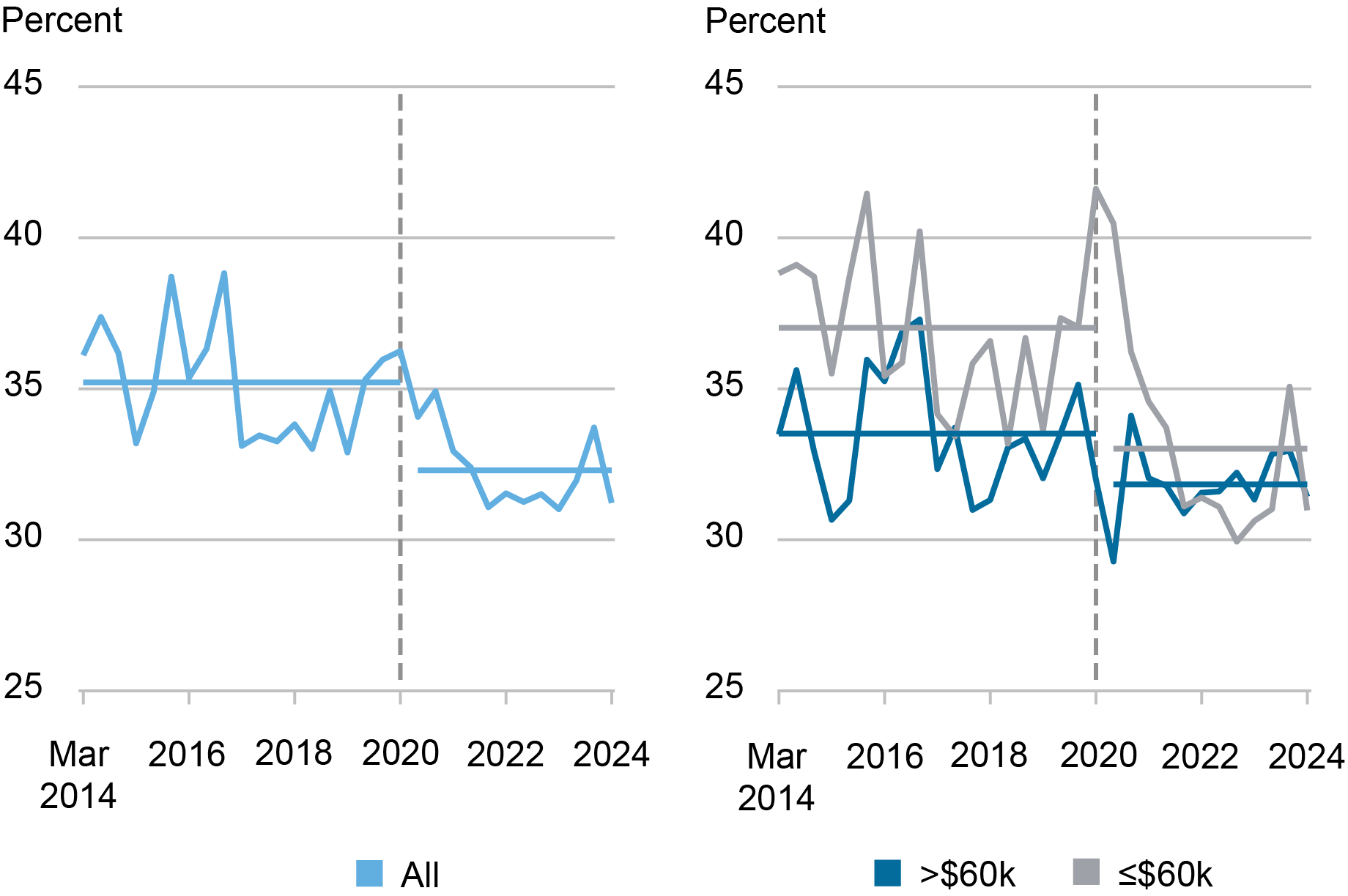

We find similar, though somewhat more attenuated, patterns for expectations about working full-time past age 67, with declines in average probabilities falling by 2.9 percentage points overall (equating to an 8.2 percent decline in future post-67 full-time employment). Again, we find larger declines for female workers (3.8 percentage points), and also for those with annual household incomes below $60,000 (4.0 percentage points), with the difference in declines between income groups being larger than for expectations about working past age 62.

Average Likelihood of Working Full-Time Past 67

Notes: The right panel shows the likelihood of working full-time past age 67 for those with annual household incomes above (dark blue line) and equal to or below (gray line) $60,000. The vertical dashed lines indicate the start of the pandemic. Horizontal lines indicate pre- and post-pandemic means.

Drivers and Implications

The pandemic and the pandemic-induced recession are behind us and the recovery of the U.S. economy is continuing, but longer-term effects of this experience linger. Although wage growth has begun to moderate, vacancies are down, and layoff and quit rates are back to pre-pandemic levels, our survey responses reveal a persistent decline in expectations of working full-time beyond ages 62 and 67. Given improvements in health and increases in life expectancy, this may be somewhat surprising. It is unclear what factors or combination of factors are driving this persistent decline: an increased preference of part-time over full-time employment; a cultural shift characterized by a rethinking of the value of work; a reflection of increased household net wealth; increased confidence about future growth in earnings and income and future financial health; a greater optimism about reaching retirement saving goals; or increased uncertainty about life expectancy post-pandemic. This represents an important topic of future research.

The pandemic-induced change in retirement expectations may continue to affect the labor market in years to come. It also can have important macroeconomic implications when consumers act on their expectations in making consumption and saving decisions. To the extent that these expectations signal actual future retirement behavior, they also have implications for future decisions by consumers about the timing of claims for social security benefits and the receipt of those benefits.

Our finding of a post-pandemic shift in retirement expectations is a prime example of the type of new consumer insights the SCE has been providing over the last decade.

Felix Aidala is a research analyst in Household and Public Policy in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gizem Kosar is a research economist in Consumer Behavior Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is an economic research advisor on Household and Public Policy Research in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Felix Aidala, Gizem Kosar, and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “The Post‑Pandemic Shift in Retirement Expectations in the U.S.,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 9, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/05/the-post-pandemic-shift-in-retirement-expectations-in-the-u-s/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics