Expectations can play a significant role in driving economic outcomes, with central banks factoring market sentiment into policy decisions and market participants forming their own assumptions about monetary policy. But how well do central banks understand the expectations of market participants—and vice versa? Our model, developed in a recent paper, features a dynamic game between (i) a monetary authority that cannot commit to an inflation target and (ii) a set of market participants that understand the incentives created by that credibility problem. In this post, we describe the game, a type of Keynesian beauty contest: its main novelty is that each side attempts, with varying degrees of accuracy, to forecast the other’s beliefs, resulting in new findings regarding the levels and trajectories of inflation.

Rules versus Discretion

The long-running “rules versus discretion” debate in economics (see Kydland and Prescott (1977) and Barro and Gordon (1983)) highlights an important tradeoff that occurs when central banks are granted discretion over monetary policy.

While discretion can be valuable in certain scenarios—such as when monetary authorities have superior information about the state of the economy—things can backfire if these authorities lack credible mechanisms that commit them to inflation targets, as this gives rise to high inflationary expectations that become self-fulfilling. As a result, central banks can end up “trapped” into creating wasteful inflation—inflation that does not affect output—despite everyone knowing that this will happen.

Most research on this topic assumes that central banks know market expectations with certainty—but what if monetary authorities do not know market beliefs, and market participants do not know authorities’ beliefs about their beliefs, and so forth? Does it matter that these actors need to forecast others’ forecasts?

Beauty Contests and Higher-Order Uncertainty

The importance of higher-order beliefs—beliefs about others’ beliefs and so forth—for macroeconomics and finance has been recognized since John Maynard Keynes analogized financial markets to beauty contests: picking a hot stock is not really about selecting a company that you like, but rather identifying one that you think everyone likes—an exercise that every other investor is also conducting simultaneously.

Unfortunately, it can be very challenging to analyze this form of uncertainty in economic models, especially in a dynamic setting. The reason is twofold. First, economic actors will use time series data to learn about payoff-relevant variables that are unobserved, resulting in expectations that (i) average past data and (ii) evolve over time as more data are observed. This means that higher-order beliefs are effectively fluctuating averages of averages of past data, and hence their dynamics are increasingly complicated. Second, this iterative process of forming forecasts of others’ forecasts might never end: if economic actors possess data not available to others, all their beliefs can remain private information, potentially forcing counterparties to continually form non-trivial forecasts of what others believe, ad infinitum.

In a recent paper, we shed light on this uncertainty problem by examining a general class of “signaling games,” that is, settings where individuals hold private information and transmit it—strategically, to their own advantage—through their actions.

Consider the following scenario. A monetary authority has private information about the optimal level of stimulus—hence, of inflation—for an economy. As the authority begins setting policy, the private sector gathers imperfect signals about the ultimate impact of the authority’s actions on the economy, and hence about the optimal level of inflation in the authority’s mind. Forecasts of inflation matter for the private sector because they are used to set nominal wages; in turn, forecasting this private sector forecast matters for the monetary authority, which tries to boost the economy by creating unanticipated inflation (inflation that exceeds market forecasts).

The difficulty is that all the data collected by the private sector need not be readily available to the authority. In this case, not knowing what information the market has seen, the authority will have to reflect on its own past actions to do the forecasting; this is because higher past inflationary stimuli make higher inflation expectations by the market more likely than if lower past inflationary stimuli had been chosen. But since the authority’s past choices were also based on its private information, the private sector may now need to forecast the authority’s belief about the market forecast of economic conditions, etcetera. This additional market forecast will be based on private signals again, and the forecasting problem gets restarted.

Inflationary Bias

Our game exhibits a classic inflation-output tradeoff: the authority has discretion over how to optimally set inflation in line with its private information about the economy, but this can conflict with the authority’s desire to stabilize output around a target. Furthermore, we assume that the authority has access to publicly available data about the market’s inflation expectations (as obtained from surveys, for example).

The authority uses that data to refine the estimates constructed using its past behavior (as described above). The accuracy of this data determines the degree of higher-order uncertainty. But so long as this data is imperfect, neither player knows exactly what the other is thinking at any point in time. Despite this complexity, we show that the problem of higher-order uncertainty can be handled successfully: a finite subset of beliefs can be used to summarize the entire hierarchy of beliefs about beliefs.

Equipped with this subset of belief states, we can compute the inflationary bias: inflation that is anticipated by everyone and is therefore costly for the economy because it departs from the optimal level of inflation without being able to affect output. This form of wasteful inflation can arise when the authority has a desire to raise output above its natural level: for instance, if the market expects no inflation, the central bank will have an incentive to create it to boost output. In equilibrium, then, the market must correctly anticipate these incentives, and inflation expectations are formed in such a way that the central bank finds it optimal to fulfill them. The credibility problem leads to an inferior outcome.

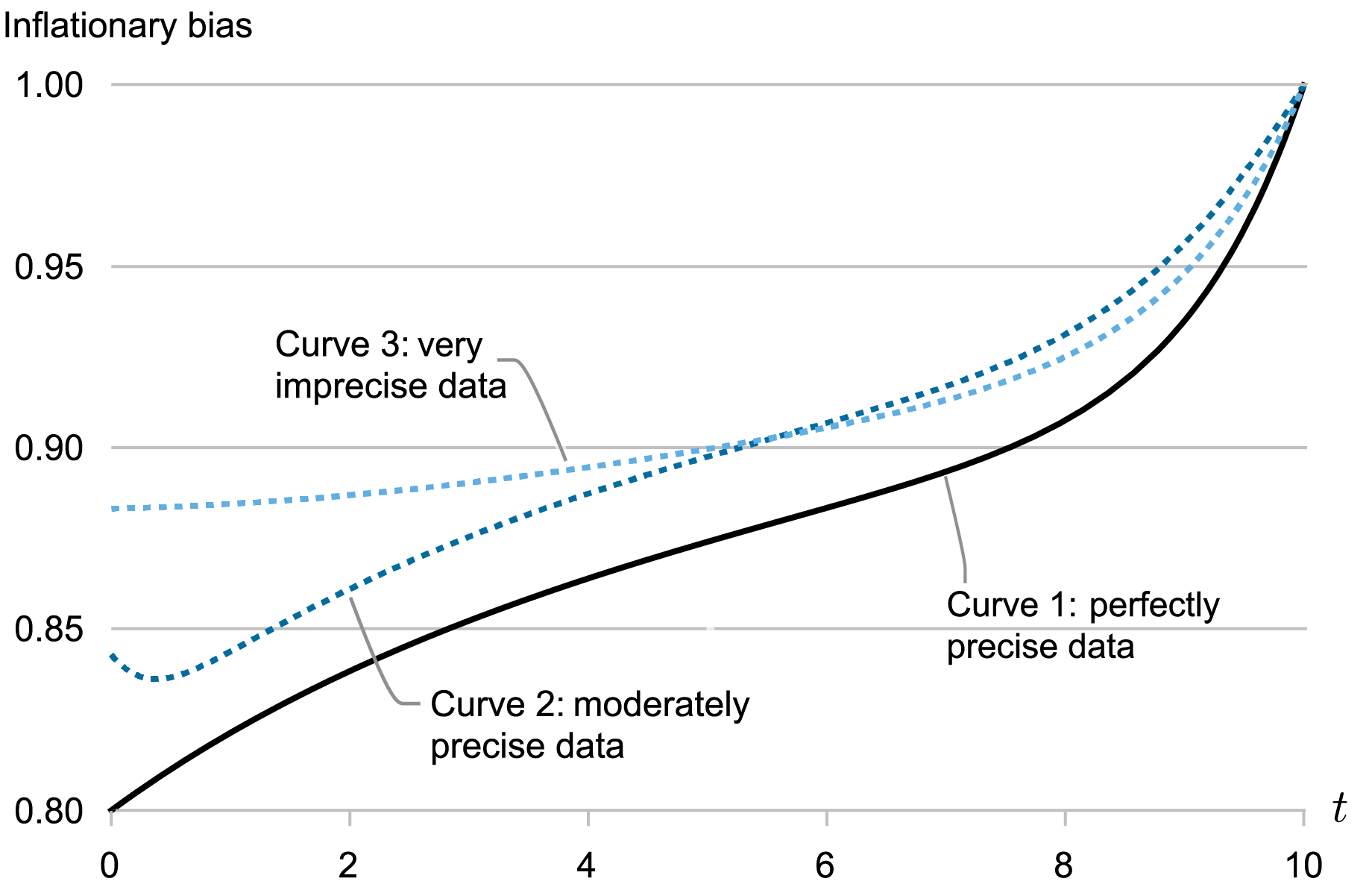

The following chart shows the time paths of such inflationary biases in three instances of our model. Curve 1: The central bank gathers perfectly precise data about market expectations, so the authority knows what the market knows. Curve 2: The data are moderately imprecise. Curve 3: The data are very imprecise and there is substantial higher-order uncertainty.

Inflationary Bias Varies According to the Accuracy of Inflation Expectations Data

The upward slope of all three curves reflects the dynamic costs from creating inflation: trying to surprise the economy today can anchor market expectations at higher levels, making it more costly to surprise the economy in the future—the authority therefore creates little inflation early on, but the credibility problem grows as the end of the relevant horizon approaches. However, the chart also reveals that, when there is higher-order uncertainty, more inflation is created (curves 2 and 3 are higher than curve 1). The reason is the “average about averages” notion explained earlier: as beliefs about beliefs are aggregates of past aggregates of past data, these beliefs are more sluggish in responding to new data. This means that market beliefs will respond less to inflation surprises. In turn, the dynamic costs that discipline the central bank are reduced, and more inflation is created.

As the quality of expectations data worsens—moving from curve 2 to curve 3—beliefs become more sluggish and inflation is higher early on when the authority begins setting policy, consistent with the previous logic. But note that things can reverse as time progresses: the inflationary bias can fall, reflected in curve 3 eventually being lower than curve 2. This is due to a strategic effect. Indeed, with less accurate data about market expectations, the authority relies more heavily on its past behavior to forecast what the market knows. As the authority uses its forecast to set policy, its actions become more informative, and hence market beliefs gain more responsiveness (consider the opposite extreme: if the authority does not transmit information, the market does not have to update). In other words, the intrinsic sluggishness of market expectations is offset because more information gets transmitted.

In summary, in economies where central banks lack commitment mechanisms for policy objectives, beauty contests between monetary authorities and markets exacerbate the credibility problems at play. Improving the accuracy of data about market expectations likely mitigates this problem, but monetary authorities can still appear to be less committed to low inflation at some points in time.

Gonzalo Cisternas is a financial research advisor in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Aaron Kolb is an associate professor of business economics and public policy at Indiana University Kelley School of Business.

How to cite this post:

Gonzalo Cisternas and Aaron Kolb, “The Central Banking Beauty Contest,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, September 30, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/09/the-central-banking-beauty-contest/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics