Women’s labor force participation grew precipitously in the latter half of the 20th century, but by around the year 2000, that progress had stalled. In fact, the labor force participation rate for prime-age women (those aged 25 to 54) fell four percentage points between 2000 and 2015, breaking a decades-long trend. However, as the labor market gained traction in the aftermath of the Great Recession, more women were drawn into the labor force. In less than five years, between 2015 and early 2020, women’s labor force participation had recovered nearly all of the ground lost over the prior fifteen years. Then the pandemic hit, erasing these gains. In recent months, as the economy has begun to heal, women’s labor force participation has increased again, but there is much ground to be made up, especially for Black and Hispanic women. A strong labor market with rising wages, as was the case in the years leading up to the pandemic, will be instrumental in bringing more women back into the labor force.

Participation Was Closing In on a Record High before the Pandemic Hit

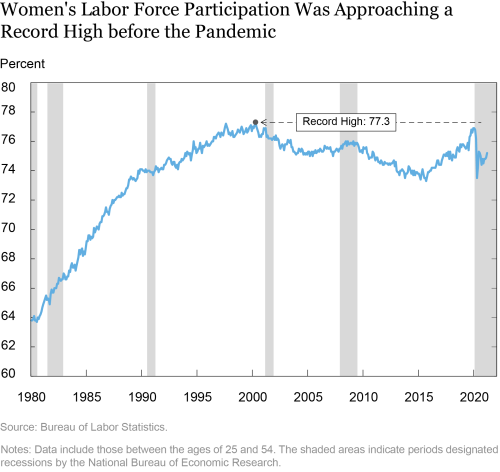

Women’s labor force participation climbed steadily until around the year 2000, shown in the chart below for prime-age women, reaching a peak of 77.3 percent. Then, between 2000 and 2015, the labor force participation rate fell a steep four percentage points to 73.3 percent, slightly less than the corresponding decline for prime-age men during this period. This decline in women’s labor force participation has been well documented, with researchers attributing it to a combination of demand side factors, such as reduced job opportunities due to trade and technology, and supply side factors, such as demographic shifts and greater access to programs such as disability insurance and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). What may be less well known—and certainly less studied—is that between 2015 and 2020, prime-age women’s labor force participation increased by 3.5 percentage points, nearly erasing the entire decline of the prior fifteen years. This increase was nearly three times greater than that seen for men.

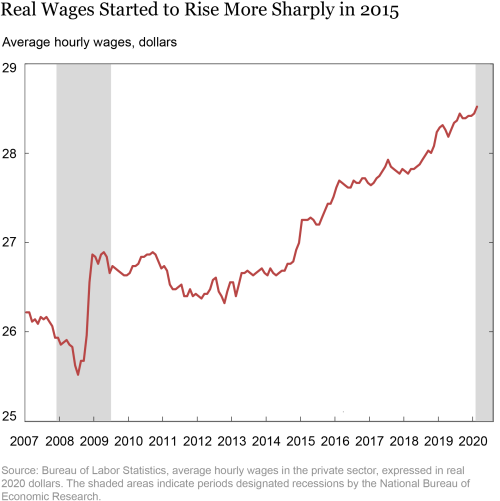

What brought more women into the labor market? It is unlikely that many of the structural factors that contributed to the prior period’s decline—such as the displacement effects of trade and technology or demographic shifts—changed quickly enough to bring such a rapid change in trajectory. In fact, many of these economic forces continued to put downward pressure on labor force participation. Rather, a historically strong labor market with rising wages for a sustained period were a likely cause. After a period of sluggish growth and slack labor markets in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession, real wages began picking up strongly in 2015, as shown in the chart below, which plots real average hourly earnings. This strong growth in wages suggests that labor markets tightened considerably during this period, pushing up wages and bringing more women (and men) into the labor market.

Then the pandemic hit. Women’s labor force participation fell by well over three percentage points in just two months, between February and April 2020, reversing nearly all of the gains made between 2015 and 2020. This sharp decline is partly attributable to an increase in childcare responsibilities due to in-person school and daycare closings during the pandemic, a responsibility that tends to fall disproportionately on women. Participation has since recovered as economic conditions have improved and schools have begun to reopen, though as of March, a year into the pandemic, the labor force participation rate for prime-age women remains almost two percentage points off its pre-pandemic level.

An Uneven Experience

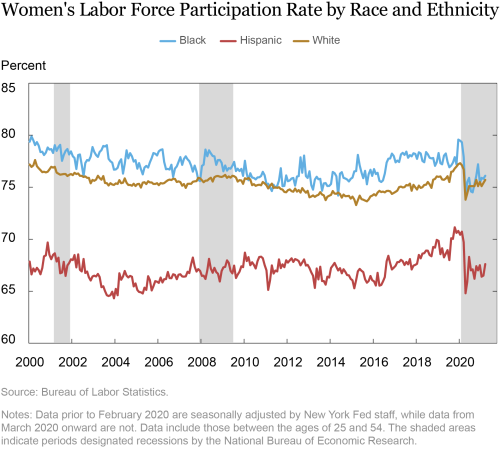

These ups and downs in labor force participation have not occurred equally among all women, as the chart below shows. Black women saw a decline of around five percentage points between 2000 and 2015, compared to a decline of roughly three to four percentage points for Hispanic and white women. When participation began to increase again between 2015 and early 2020, both Black and white women came close to recovering all of the ground that was lost and were approaching record highs. Hispanic women—whose labor force participation tends to be relatively low—saw participation exceed its previous peak by a full percentage point by early 2020.

However, when the pandemic hit, Black and Hispanic women saw much more sizeable declines in participation than white women, 5.2 and 5.9 percentage points, respectively, compared to 3.3 percentage points. The sharper decline may be due at least in part to higher rates of COVID infections among these groups, school closings leaving students at home requiring care that occurred at higher rates in communities where people of color are in the majority, as well as these groups being less able to telecommute during the pandemic. And, as of March 2021, labor force participation rates for these two groups remains 3.2 and 3.1 percentage points below pre-pandemic peaks, compared to about 1.4 percentage points for white women. Thus, Black and Hispanic women have more than twice the ground to make up compared to white women.

Looking Ahead

Will women’s labor force participation reach the highs that were seen before the pandemic hit? As more people are vaccinated and the economy continues to recover, and, importantly, as in-person schools and daycare fully reopen, participation should continue to rise, possibly quite rapidly. As was the case before the pandemic, a strong labor market with rising wages for a sustained period will help set the stage for another comeback in women’s labor force participation, particularly if more flexible work arrangements brought on by adapting to work during the pandemic persist.

Jaison R. Abel is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jaison R. Abel is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz, “Women’s Labor Force Participation Was Rising to Record Highs—Until the Pandemic Hit,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 10, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/04/womens-labor-force-participation-was-rising-to-record-highsuntil-the-pandemic-hit.html.

Related Reading

Some Workers Have Been Hit Much Harder than Others by the Pandemic (February 2021)

Understanding the Racial and Income Gap in Commuting for Work Following COVID-19 (February 2021)

Black and White Differences in the Labor Market Recovery from COVID-19 (February 2021)

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics