The difficult economic and financial issues facing the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico have remained very much in the news since our post on options for addressing its fiscal problems appeared last fall. That post was itself a follow-up on a series of analyses, starting with a 2012 report that detailed the economic challenges facing the Commonwealth. In 2014, we extended that analysis with an update where we focused more closely on the fiscal challenges facing the Island. As the problems deepened, we have continued to examine important related subjects ranging from positive revisions in employment data, to the credit conditions faced by small businesses, to understanding emigration, and to considering how the Commonwealth’s public debts stack up. In most of this work, we have focused on how policymakers could help to address the immediate issues facing the Island and its people. The U.S. Congress and the Obama Administration took action in June to provide a framework to help address Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis. But much remains to be done to address these ongoing problems, which represent a significant impediment to economic growth in the short run. It also seems important to revisit the question of the prospects for reviving longer-run growth in the Commonwealth. These concerns were underscored by projections published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the April edition of the World Economic Outlook that forecast Puerto Rico’s real GDP and population to decline through 2021.

Over the next week, Liberty Street Economics will present a series of posts on Puerto Rico, drawing on expertise from different areas of the New York Fed. Today we provide some brief background on the sustainability of the Commonwealth’s fiscal trajectory, and introduce the remaining posts in the series. As we pointed out in our 2014 report, Puerto Rico’s current debt burden is very high relative to that of mainland states and other economies, and Puerto Rico’s own history. Puerto Rico’s total public sector debt amounts to about $70 billion, including the debt of the central government, public corporations, and municipal governments. At about 100 percent of GNP, this debt level is almost four times greater than the most heavily indebted mainland state (New York), is in the upper tail of the distribution of advanced economies, and is among the highest of all emerging market economies. The Commonwealth’s debt-to-GNP ratio increased by nearly 35 percentage points over 2003–13 versus a median increase of only 1.7 percentage points for the fifty mainland states (the data used here for the mainland states come from the U.S. Census Bureau).

Another way to look at Puerto Rico’s debt is to focus on debt that is issued by entities whose repayment capacity derives primarily from taxes on incomes and economic activity generated in Puerto Rico, or whose primary purpose is to serve as financing vehicles for government entities. We showed in our blog post from last November that this type of debt amounts to roughly $50 billion. Debt service on these obligations amounts to about one-third of broad central government revenues excluding federal transfers, with interest alone amounting to 20 percent of revenues—figures that are much higher than for mainland states. On top of this huge debt load, Puerto Rico faces a net pension liability of $43.7 billion as of June 2014, or about 60 percent of GNP.

Although Puerto Rico has made important fiscal adjustments over the last several years, the efforts have narrowed Puerto Rico’s borrowing needs by less than targeted, while at the same time Puerto Rico has lost access to market funding. At this point, it has become clear that Puerto Rico is unable to service its debt on its originally contracted terms, as reflected in the government’s inability to make full debt service payments that were due in May and July of this year. Just before the deadline for the July major debt service payments, the U.S. Congress and the Administration enacted legislation designed to help provide a legal and policy framework for putting the Island on a sustainable fiscal trajectory, including appointment of a fiscal oversight board. Prior to the federal action, the Puerto Rican Governor had created a Working Group for the Fiscal and Economic Recovery of Puerto Rico, which released a Fiscal and Economic Growth Plan (FEGP) in September of last year (subsequently updated in January). The FEGP projected substantial financing gaps over the next ten years and specified measures to reduce those gaps, but indicated that Puerto Rico would also have to implement significant debt restructuring. Consistent with the proposals in the FEGP, the Commonwealth also had been seeking a consensual comprehensive restructuring of its debt which, while complex, essentially would deliver substantial cuts to the Island’s debt service over the next ten years and beyond.

Ultimately, achieving “fiscal sustainability” will be a complex process involving sacrifices and compromises by both creditors and debtors. A frequently used measure of fiscal sustainability for countries is a test of whether the ratio of government debt to GDP is likely to be on a stable or declining trajectory, or is on a path to grow indefinitely, in which case the fiscal position is judged to be not sustainable. As discussed in the appendix to our 2014 report, the evolution of the ratio of debt to GDP is determined by economic growth, interest rates, and the size of the government’s “primary balance” (revenues minus expenditures excluding interest and principal payments on debt).

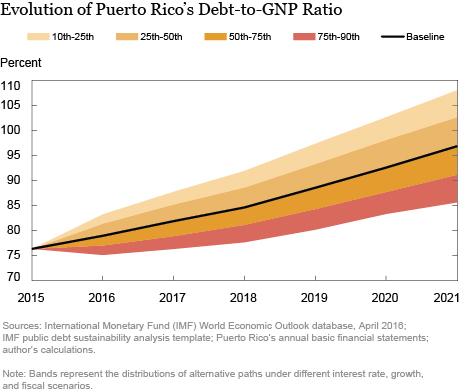

The present situation for Puerto Rico can be illustrated with a fan chart generated by a standard debt sustainability analysis template that is used by the IMF in its reviews of member countries. The chart below shows a forecast for the debt-to-GNP ratio derived from the IMF’s projections for Puerto Rico contained in its April 2016 World Economic Outlook, and distributions of alternative paths derived from simulated interest rate, growth, and fiscal shocks. The IMF’s projections through 2021 foresee economic growth averaging negative 1 percent, at a compounded annual rate, and primary balances averaging negative 0.1 percent per year. Clearly, the chart demonstrates that under the IMF’s projections, Puerto Rico’s expected fiscal trajectory is unsustainable. The debt burden continues to grow throughout the forecast horizon.

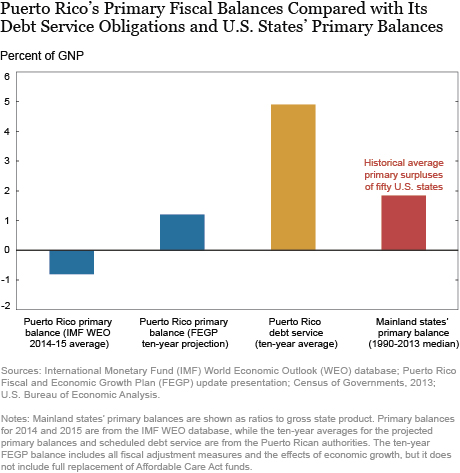

Given Puerto Rico’s difficult starting point, achieving fiscal sustainability will require both lasting fiscal reforms and significant adjustments to its debt service burden. The amounts of these adjustments will be a point of discussion, but it is indisputable that the financing gap is quite large, given the loss of market access. As illustrated in our next chart, the IMF estimates that Puerto Rico’s general government primary fiscal balance ran deficits averaging about 0.8 percent of GNP over the past two years; general government primary deficits were larger in earlier years, averaging 2.6 percent of GDP from 2004–13, according to the Commonwealth’s annual financial reports. The Puerto Rican government’s FEGP outlines a strategy that would raise the primary balance to a surplus of a bit over 1 percent of GNP over ten years. The FEGP assumes the loss of certain funds under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), in accordance with current law; if the ACA funds are replaced, the FEGP foresees a primary surplus averaging close to 3 percent of GNP. These projected surpluses are insufficient to cover the nearly 5 percent of GNP in average annual debt service payments the Island faces over the next ten years under its current debt structure. As a point of comparison, the fifty mainland states have achieved average primary surplus ratios of close to 2 percent of GNP since 1990.

Ultimately, achieving fiscal sustainability depends greatly on reinvigorating economic growth, which has been unsatisfactory in Puerto Rico in the past decade. Stronger growth will increase tax revenues, providing more margin to reduce the deficit while maintaining essential public services, and gradually bend the debt-to-GDP trajectory in a more favorable direction. In the rest of the series, we will analyze a set of factors believed to be important in generating sustained growth. In particular, our authors will look at the quality and size of the workforce, including how it is impacted by workers’ migration decisions, as well as credit market and financial developments. Taken as a whole, the series suggests that Puerto Rico’s ability to sustain and improve its workforce will be a significant determinant for achieving robust growth in the long run.

Also in the Series

:

Migration in Puerto Rico: Is There a Brain Drain?

Puerto Rico’s Shrinking Labor Force Participation

Human Capital and Education in Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico’s Evolving Household Debts

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Hunter L. Clark is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Integrated Policy Analysis Group.

Hunter L. Clark is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Integrated Policy Analysis Group.

Giacomo De Giorgi is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Giacomo De Giorgi is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Andrew F. Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Andrew F. Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Hunter L. Clark, Giacomo De Giorgi, and Andrew F. Haughwout, “Restoring Economic Growth in Puerto Rico: Introduction to the Series,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), August 8, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/08/restoring-economic-growth-in-puerto-rico-introduction-to-the-series.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

The World Bank ranks doing business in Puerto Rico on the level of most third world nations. http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/puerto-rico/ For example PR ranks 164th in world for registering property and 134th for paying taxes. The stranglehold of a corrupt and bureaucratic government has made it nearly impossible to begin new small businesses and hire workers. For example businesses are required by law to pay Christmas bonuses to workers. Last December the PR Treasury required that every business submit audited financials to determine, firm by firm, if a company could be exempt from paying XMass bonuses due to lack of profits. At the same time the central government itself paid $120 million of Christmas bonuses to public workers while defaulting on debt payments and having no audited financials from the previous fiscal year. I appreciate this effort by the NY Fed but without addressing the deep corruption of the island a path towards real economic growth in PR will never be found.