The rising cost of a college education has become an important topic of discussion among both policymakers and practitioners. At least eleven states have recently introduced programs to make public two-year education tuition free, including New York, which is rolling out its Excelsior Scholarship to provide tuition-free four-year college education to low-income students across the SUNY and CUNY systems. Prior to these new initiatives, many states, including New York, had already instituted merit scholarship programs that subsidize the cost of college conditional on academic performance and in-state attendance. Given the rising cost of college and the increased prevalence of tuition-subsidy programs, it’s important for us to understand the effects of such programs on students, and whether these effects vary by income and race. While a rich body of work has studied the effects of merit scholarship programs on educational attainment, the same is not true for the effects on financial outcomes of students, such as debt and repayment. This blog post reports preliminary findings from ongoing work, which is one of the first research initiatives to understand such effects.

Twenty-seven states have implemented some type of merit aid program so far, the first being Arkansas in 1991. These programs vary in scope and still require payments for tuition and living expenses, but they generally provide significant reductions to in-state tuition at both public and private four- and two-year colleges to any student that clears a certain academic threshold. Some programs alter the size of the subsidy based on family income, while others provide a set dollar amount. Investigating the effects of these programs gives us insight into the implications of lowering college cost.

Our analysis is the first to use a nationwide data panel that links students’ educational records with their debt outcomes to understand the effect of such merit scholarship programs on students’ short- and long-term financial outcomes. Our data set leverages a unique merger between two large data sets: the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel (CCP) and the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC). The CCP is made up of anonymized consumer credit records from the Equifax credit bureau, while the NSC compiles individual-level postsecondary education records. The NSC currently covers 97 percent of all college enrollments, but its coverage rate was less complete for cohorts that attended college before the mid-1990s. We therefore use 1978-88 birth cohorts in our analysis.

In this post, we leverage differences in access to these merit aid programs to estimate their effects on college entry, student debt, and repayment rates. We assume a person is eligible for merit aid if she turned 18 in a state that has already implemented a merit aid program. We compare the outcomes of students who were merit-eligible because of their home state and year of birth with those of students who were not merit-eligible (either because they went to college before a state’s merit aid program was implemented or because their home state never implemented such a program). We control for time-invariant characteristics of cohorts at each age as well as time-invariant characteristics of states by each age (for example, capturing permanent differences in state policies and in education and labor market characteristics)—factors that may affect different ages differently. Further, our findings are robust to the inclusion of time-varying state characteristics (such as idiosyncratic conditions in labor and housing markets and other variations in economic and political conditions across states and years).

While the above approach allows us to identify the average effect of merit eligibility on students’ outcomes, it is also important to understand whether these effects vary across demographic groups. Our data do not allow us to observe race or family income, but the CCP contains geographical information for individuals over time. This enables us to identify characteristics of students’ neighborhood of residence when they first entered our data, mostly between ages 18 and 21.

Defining neighborhoods as zip codes, we include, for each zip code, the average adjusted gross income in 2001 (from the U.S. Treasury) and data on racial composition, specifically the shares of black and Hispanic residents in 2000 (from the 2000 U.S. Census). In this blog post, we limit our focus to zip codes with high shares of low-income and black residents, with the former defined as zip codes falling in the lowest quartile of the adjusted gross income distribution, and the latter as those falling in the top quartile of the black population share distribution (zip codes we refer to as “high-black neighborhoods”). In separate analysis, we also study outcomes for students from high-Hispanic neighborhoods, the results of which we describe in brief below.

First, we study the average effect of merit eligibility on the probability of going to college at each age between 18 and 30. In results not reported here, we find no evidence that merit-eligible individuals are more likely to go to college, consistent with some of the previous literature. We further find no evidence that individuals who belonged to a merit-eligible cohort and came from low-income neighborhoods or high-black or high-Hispanic neighborhoods were more likely to enter college at any age.

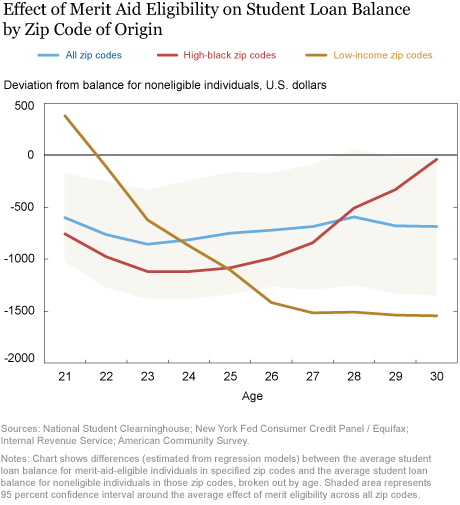

Second, we study the average effect of merit eligibility on student loan balances over the same age range. While we don’t find that merit aid programs have an effect on college attendance, they do appear to have a strong and persistent negative effect on student loan balances, both during and after the typical college-age period. On average, student loan balances were $500 to $1,000 lower for people in their mid-to-late 20s belonging to cohorts that were eligible for merit aid programs (see the blue line in the chart below). At age 24, we estimate that individuals eligible for merit aid have about 14 percent less student loan debt (a difference of $825) than the average student loan balance for the overall population at that age.

The gold line in the chart below shows that the negative effect on debt balances is even more pronounced (up to twice as large) for merit-eligible individuals from low-income neighborhoods after their early 20s. Students from high-black neighborhoods (red line) also have declines in student loan balances during their 20s, but there is no evidence that they had a lower balance at age 30. These effects at age 30 are not statistically different between groups. For simplicity, we only present confidence intervals around the average line (the tan shading) in each of the figures below.

The results for merit-eligible individuals from high-Hispanic neighborhoods are qualitatively similar to those for students from high-black neighborhoods, but there are some important differences. Once again, we do not find that merit aid eligibility has any effect on the probability of college attendance at any age. However, we find that merit-eligible individuals from high-Hispanic neighborhoods have lower student loan balances and lower delinquency rates in their mid-to-late 20s than those from high-black neighborhoods.

Thus, while merit eligibility does not increase the rate of college attendance, it reduces the debt burden of students who go to college. When merit aid programs cover most or all of undergraduate tuition, there is less need to take out debt, although many may still do so to cover room, board, and other expenses. Due to the lack of an overall enrollment effect, we hypothesize that the drop in student loan balances for merit-eligible individuals is mostly spread across individuals who would have gone to college in the absence of merit aid programs; it’s not a result of fewer individuals going to college. Note that the average effects we estimate apply to all individuals of a given age living in a state with a merit-aid program. Clearly, not all such individuals are eligible for merit aid, and not all merit-aid-eligible high school graduates end up attending college. When scaled by an average college-attendance rate—65 percent by age 30 during our period of analysis—our estimates imply a 1.5 percent reduction in the average likelihood of any student loan borrowing and an average reduction of $1,052 in student debt for college-going cohorts in merit-aid states.

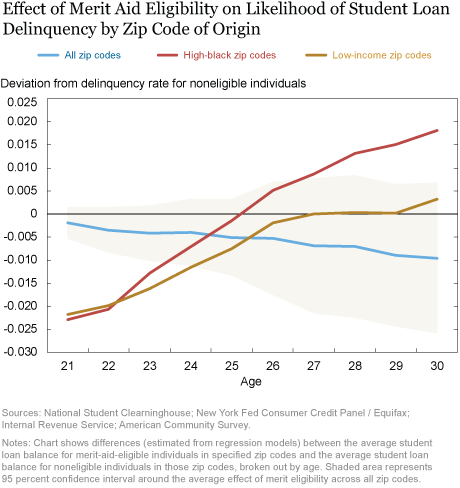

Finally, we also examine dynamics of student loan delinquency and default. The proportion of all individuals who become delinquent on student debt payments by age 30 is 14 percent—compared to figures of 18 percent and 19 percent for individuals from low-income and high-black neighborhoods, respectively. While we find that on average, merit-eligible individuals are slightly less likely to experience a delinquency or default on their student loan, these effects are not statistically different from zero (blue line in figure below). However, we find important variations when we distinguish between individuals from different neighborhoods. Students in merit-aid-eligible cohorts originating from low-income (gold line) and high-black (red line) neighborhoods are much less likely to be delinquent on student loans until their mid-20s, likely because merit aid eases their financial constraints and helps them stay current on their payments. In contrast, by their late 20s, merit-eligible students from low-income and high-black neighborhoods are slightly more likely to be delinquent than the average merit-eligible student (though they remain statistically indistinguishable from the average).

Our findings have important implications for the debate over college cost, the impact of tuition subsidies, and “free college.” We do not find any evidence that lowering the cost of college through merit-aid programs increases college enrollment. In contrast, we find significant reductions in the incidence and magnitude of student loan balances among students. While we do not find significant reductions in delinquency for individuals in merit-aid-eligible cohorts overall, we find that such students coming from low-income and high-black neighborhoods were somewhat more likely to be delinquent by age 30, although these effects are not statistically different between groups. In ongoing analysis, we are examining the mechanisms behind higher delinquencies for merit-eligible individuals from less advantaged neighborhoods: perhaps the explanation has to do with the fact that they are substituting into other types of debt as student debt declines. Moreover, we are analyzing the effects of merit eligibility on a broader range of measures of financial and economic well-being—essential steps toward a fuller understanding of the implications of “free college” and other tuition-reduction programs. So, stay tuned for more!

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

William Nober is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

William Nober is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Rajashri Chakrabarti, William Nober, and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “Is Free College the Solution to Student Debt Woes? Studying the Heterogeneous Impacts of Merit Aid Programs”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 10, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/09/is-free-college-the-solution-to-student-debt-woes.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics