Once a bank grows beyond a certain size or becomes too complex and interconnected, investors often perceive that it is “too big to fail” (TBTF), meaning that if the bank were to become distressed, the government would likely bail it out. In a recent post, I showed that the implicit funding subsidies to systemically important banks (SIBs) declined, on average, after a set of reforms for eliminating TBTF perceptions was implemented. In this post, I discuss whether these subsidies increased again during the COVID-19 pandemic and, if so, whether the increase accrued to large firms in all sectors of the economy.

Expected Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on TBTF Subsidies

Unlike the global financial crisis (GFC), the COVID-19 pandemic did not directly affect banks. Rather, nonfinancial firms that had to curtail or shut down business activities due to health restrictions were the most stressed. Nevertheless, banks that lent to hard-hit businesses might also suffer if many borrowers defaulted on their loans. Indeed, there was concern that a wave of corporate bankruptcies would overwhelm courts. Such concerns, if widely shared, might increase expectations of large bank bailouts and implicit subsidies.

Extensive fiscal and monetary support, and supervisory measures that provided regulatory relief, prevented the worst-case economic outcomes. Consequently, widespread bankruptcies have not materialized. However, there is continuing concern regarding large credit losses to banks in the near future.

Relative Returns of the Largest Financial Firms Changed during the Pandemic

If SIBs are viewed as likely to be bailed out, they can issue debt and equity at a discount to the fair market price, thus receiving an implicit funding subsidy that, in turn, creates a competitive disadvantage for non-SIB firms. As in my previous post, I estimate the implicit subsidy by first constructing a TBTF risk factor, and then estimating exposures to this factor for SIBs and other large financial firms, as detailed in my related study.

The TBTF risk factor is based on the idea that the largest financial firms have a higher probability of bailout and so investors perceive them to be less risky and have lower expected equity returns, relative to other large financial firms. Empirically, the TBTF factor is constructed by taking a short equity position on the largest 8 percent of financial firms globally and a long equity position on the next largest 8 percent of financial firms globally. The returns to this factor are expected to be positive, and represent in part the systemic risk premium—the additional compensation that investors require to hold less systemically important firms.

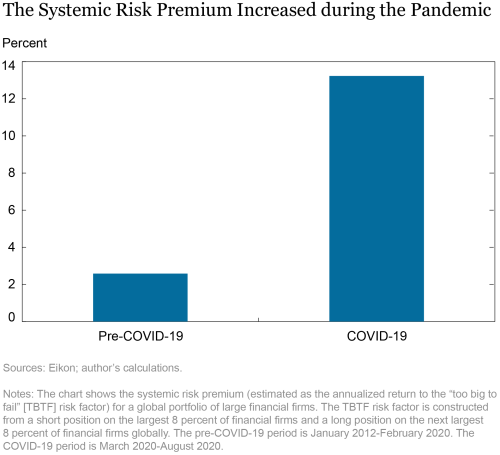

The chart below shows estimates of the systemic risk premium using equity returns data of a global portfolio of financial firms from Asia (excluding Japan), Canada, Europe, Japan, and the United States. To focus on the recent pandemic, the sample starts in 2012, once TBTF reforms started to be implemented. On an annualized basis, the systemic risk premium increases from 2.58 percent in the pre-COVID-19 period (January 2012 to February 2020) to 13.23 percent in the COVID-19 period (March 2020-August 2020). In other words, during the pandemic, investors have required more compensation for holding the stocks of large financial firms, as compared to the very largest financial firms. One explanation may be that investors are putting a premium on safety during the pandemic, and the perceived default risk of even large firms shot up relative to that of the very largest firms.

Implicit Subsidies to SIBs before and after the Pandemic

In order to estimate the implicit subsidy to SIBs, we consider the exposures of SIBs and other large non-SIB financial firms to the TBTF risk factor. Since SIBs benefit when they are perceived to be TBTF, they should have a lower TBTF risk exposure than non-SIBs. This differential exposure is a measure of the subsidy to SIBs. Our methodology accounts for the systematic risk of large banks, or how much their returns co-move with the market return. This is important because large banks are expected to have large systematic risk, which should be separated out when estimating their systemic risk.

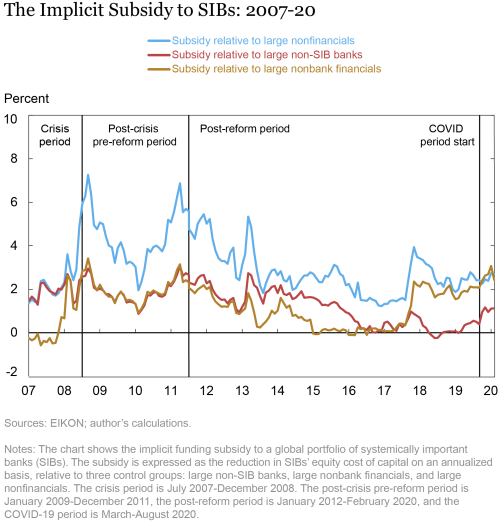

In the chart below, we show the evolution of the implicit TBTF subsidy for the global portfolio, expressed as a lower equity cost of capital for SIBs relative to three other groups: large non-SIB banks, large nonbank financials, and large nonfinancial firms. For all three comparisons, the implicit subsidies have generally decreased since their peak during the GFC, except for a second smaller peak around 2011 when the European debt crisis occurred, and other smaller increases that cannot be attributed to specific events. With the start of the COVID-19 period, subsidies increase. However, because subsidy levels were low prior to the pandemic, TBTF subsidies remained at moderate levels by historical standards even after this increase.

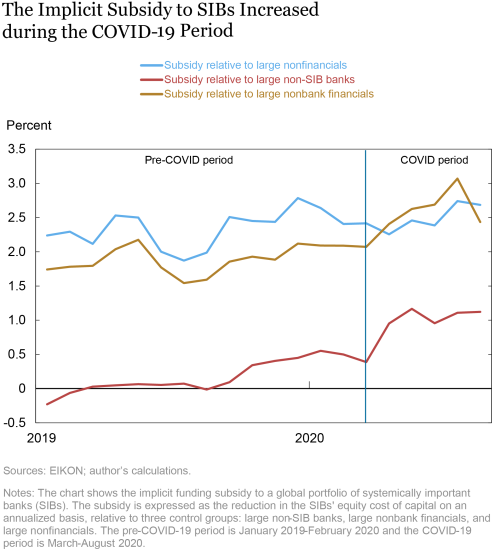

To get a better understanding of the evolution of the subsidy in the pandemic era, we zero in on the two recent years, 2019 and 2020 (see chart below). Except when using large nonbank financials as the control group, subsidies increase at the beginning of the COVID-19 period and peak in summer. A regression analysis shows a statistically significant increase in subsidies of between 50 and 80 basis points (depending on the control group) between March and August of 2020, from a pre-COVID-19 average of about 100 basis points between January 2012 and February 2020.

Did Funding Advantages Increase for All Large Firms?

Are the increased funding advantages specific to large banks or do they accrue to large firms broadly? The pandemic was particularly adverse for small- and medium-sized firms and to the relative advantage of large firms in many industries. If so, our results might reflect this broad-based structural economic change rather than a TBTF subsidy.

We examine this question by constructing a nonfinancial size factor, analogous to the TBTF factor but using large nonfinancial instead of large financial firms. This factor is constructed at the industry level, given differences in how COVID-19 affected different industries. Then, we evaluate the funding advantage of the largest 10 percent of nonfinancial firms in each industry, relative to the next largest 10 percent of nonfinancial firms. An increase in this funding advantage during the pandemic, especially in the hardest-hit industries, would suggest an economy-wide shift towards large firms.

Our results show that in the oil and gas, retail, and transportation sectors—all disproportionately affected by the pandemic—the largest firms increase their funding advantage during the pandemic, but the statistical significance of the change is weak or absent. In the remaining sectors—including the hard-hit entertainment and hospitality sector—the funding advantage of the largest firms decreased during the pandemic. Hence, the evidence of an economy-wide increase in funding advantages for large firms is mixed.

Final Thoughts

While our findings suggest that implicit subsidies to SIBs increased during the pandemic, our calculations were carried out in a period of unprecedented government support. Such support may have muted estimates of bank risk (and required subsidies) or, alternatively, reinforced expectations of bailouts in spite of reforms. Moreover, our subsidy estimates are based on equity prices alone. Future work should assess whether using alternative asset prices yields a different perspective.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Asani Sarkar, “Did Subsidies to Too-Big-To-Fail Banks Increase during the COVID-19 Pandemic?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 11, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/02/did-subsidies-to-too-big-to-fail-banks-increase-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.html

Related Reading

The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Fed’s Response

Did Too-Big-To-Fail Reforms Work Globally?

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

In reply to Bill Nelson: Thanks for your comment. The average TBTF factor return from May to September 2020 (when the current data end) is 10.0% on an annualized basis, compared to 13.2% from March to August (the value reported in the first chart). If you want to compare to a 6-month period, the average return from April to September is 15.6% on an annualized basis.

The first exhibit shows that the equities of the largest financial institutions did poorly in the pandemic period (March-August 2020)relative to the equities of merely large financial institutions. The post attributes the difference to a reduction in the expected returns investors demand to hold the equities of the largest institution. But such a reduction would cause a capital gain in the stocks of the largest financial institutions when it occurred that would have resulted in the equities of those firms doing well, not poorly. If you are just going to show a 6-month average, why not show the May-October average so that you get a reading on the posited new level of required returns that, while noisy, is at least not corrupted by the associated capital gain? For additional discussion see https://bpi.com/the-fact-that-big-banks-stock-prices-got-hammered-this-spring-hardly-proves-they-are-tbtf/