As we discussed in our previous post, millions of mortgage borrowers have entered forbearance since the beginning of the pandemic, and more than 2 million remain in a program as of March 2021. In this post, we use our Consumer Credit Panel (CCP) data to examine borrower behavior while in forbearance. The credit bureau data are ideal for this purpose because they allow us to follow borrowers over time, and to connect developments on the mortgage with those on other credit products. We find that forbearance results in reduced mortgage delinquencies and is associated with increased paydown of other debts, suggesting that these programs have significantly improved the financial positions of the borrowers who received them.

Forbearance and Mortgage Delinquency

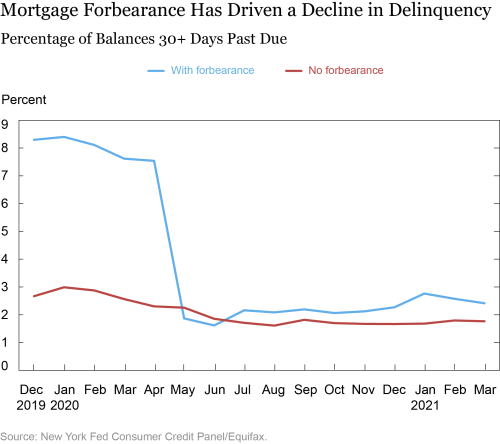

Since March 2020, we have observed more than 6.1 million mortgagors enter forbearance. As noted in our previous post, these forbearance participants were much more likely to be delinquent prior to the pandemic than the general population of mortgagors. One of the benefits of forbearance for these previously delinquent borrowers is that commencement of forbearance is often coincident with a “cure”: a change in mortgage status to “current.” That is, for many borrowers, mortgage delinquencies are wiped away as the borrower enters forbearance, at least temporarily. (These status changes come without evidence of payment, supporting the conclusion that the cure is the result of an administrative change rather than a true cure. Mortgage servicer reports to investors, as opposed to credit bureaus, show these loans as delinquent. Importantly, however, these investor reports do not affect borrower credit histories.)

The first chart below shows the credit bureau reporting of mortgage status for those that entered forbearance by May 2020. Around 8 percent of the mortgages were already delinquent before entering forbearance. A great majority of those accounts that were previously delinquent are reported as “current” while in forbearance, some of them by making payments and some without one. A minority—about 30 percent of the previously delinquent accounts—retain this delinquent status throughout the period. These varying treatments upon entry into forbearance seem to depend on servicer practices. As such, current foreclosure data and delinquency statistics drawn from credit bureau data do not accurately give a clear indication of housing market stresses.

At the same time, neither does the rate of forbearance itself. Why? Because a large share of mortgagors in forbearance actually continue to make their monthly mortgage payments. Indeed, the share of borrowers who continue to make payments while in forbearance is surprisingly high: in each month since June 2020, between 30 and 40 percent of the borrowers in forbearance have made their monthly payment.

This behavior suggests that some borrowers have taken advantage of the forbearance program and skipped payments while others have applied for forbearance as an “insurance policy” against which they are not making claims, and they are reducing their balances each month as originally anticipated in the mortgage contract.

But for the 60-70 percent of forbearance borrowers who are not making payments, mortgage balances aren’t falling. In 2019, mortgagors paid off approximately 4 percent of mortgage balances by making their regular payments. By contrast, borrowers in forbearance have seen their balances increase by 1-2 percent over the course of the last year as the automatic amortization that comes from making the mortgage payment has been largely absent and the interest component of the skipped payment is added back to the balance as well. As of March 2021, among the 5 million borrowers who have taken forbearance for at least one month since the pandemic and haven’t prepaid, about 26 percent have a higher mortgage balance than a year earlier.

Mortgage Forbearance and Performance on Other Household Debts

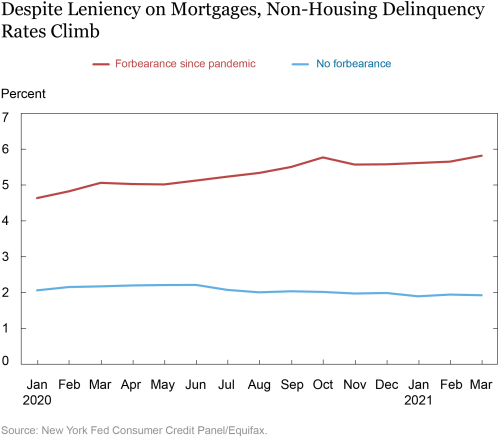

We can also use the CCP to examine the relationship between mortgage forbearance and performance on a borrower’s non-housing debts. Doing so, though, requires a slightly longer timeframe. In the chart below, we show that non-mortgage delinquency (which reflects delinquency on auto, credit card, and miscellaneous consumer debt) was persistently higher among those who had at least one month of forbearance since March 2020; indeed, prior to the pandemic this was a group of borrowers whose delinquency rates had not only been high, they had also been on the rise. (We keep student debt out of consideration here since the vast majority of student debt has been in automatic forbearance since the early weeks of the pandemic.) Immediately after March 2020, delinquency on non-housing debts leveled off briefly, but then began increasing again and stood at 5.8 percent in March 2021, a full percentage point higher than it had been one year before. In contrast, delinquency rates for those not in mortgage forbearance were roughly flat during the year ending in March 2021, at about 2 percent.

Thus we have a glass half empty/half full situation: these are clearly distressed borrowers, and mortgage forbearance provided assistance that may well have allowed them to keep their homes. Nonetheless, these borrowers were already struggling with debt repayment prior to the pandemic, and forbearance has not allowed them to close the delinquency gap with other mortgagors; instead that gap has persisted in spite of forbearance.

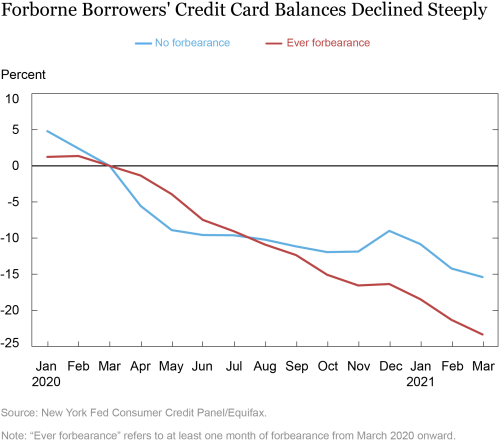

A second dimension of performance, and one that is perhaps especially interesting during the pandemic environment of reduced consumption opportunities, is debt balance paydown. We’ve noted in the past that aggregate credit card balances fell a lot in 2020, and ended the year more than $100 billion below their December 2019 level. This is the largest annual decline in credit card balances for at least two decades, and it continued into the first part of 2021. The accumulation of savings by U.S. households during the pandemic was surely a key factor in this paydown of costly credit card balances. Did mortgage forbearance play a role for those households that received it?

In the next chart, we provide some evidence for that proposition. The chart shows the relative credit card balances for mortgagors who had a forbearance after March 2020 (red) and those who never did (blue). Card balances declined for both groups, but somewhat more steadily for borrowers with forbearances: by March 2021, they had reduced their credit card balances to 23 percent below their March 2020 level. This compares with a 15 percent decline for mortgagors without a forbearance. The dollar amount of credit card paydown is even higher for those with forbearance, since their initial average amount of credit card debt as of March 2020 was significantly higher at $9,000 compared to $6,000 for those without forbearance. As a result, a typical household in mortgage forbearance has reduced its credit card debt by $2,100 over the last year, compared to $900 for a mortgagor not in forbearance.

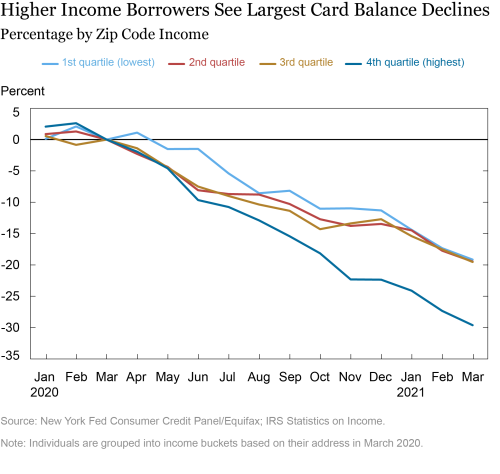

The ability to reduce credit card obligations over the past year has not been equal across different types of mortgage borrowers in forbearance. The next chart shows that the balance decline for neighborhoods outside of the top income quartile has now reached 20 percent below the March 2020 level. In the highest income neighborhoods, which benefited from the largest share of mortgage relief as shown in the previous blog post, credit card balances have fallen more: 30 percent as of March.

Conclusion

Our brief review of what happens to borrowers when they’re in forbearance produces some interesting conclusions. First, many previously delinquent borrowers are marked “current” as they enter forbearance, even if they don’t make a payment. As a consequence, credit bureau measures of mortgage delinquency must be viewed cautiously in a period of widespread forbearance. Second, a substantial share, around 30-40 percent, of borrowers who get forbearance nonetheless continue to make payments. This will have implications for our expectations for how delinquency measures will change when forbearance ends. Finally, mortgagors in forbearance have been able to pay down their credit cards faster than those not in forbearance, especially in higher income areas. In our next post, we will shift our focus to a group of mortgage borrowers who stand out from the crowd for a different reason: they own a small business.

Andrew F. Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Andrew F. Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is an officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is an officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is a senior data strategist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is a senior data strategist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Andrew Haughwout, “What Happens during Mortgage Forbearance?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 19, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/05/what-happens-during-mortgage-forbearance.html.

Additional Posts in This Series

Keeping Borrowers Current in a Pandemic

Small Business Owners Turn to Personal Credit

What’s Next for Forborne Borrowers?

Press Briefing

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics