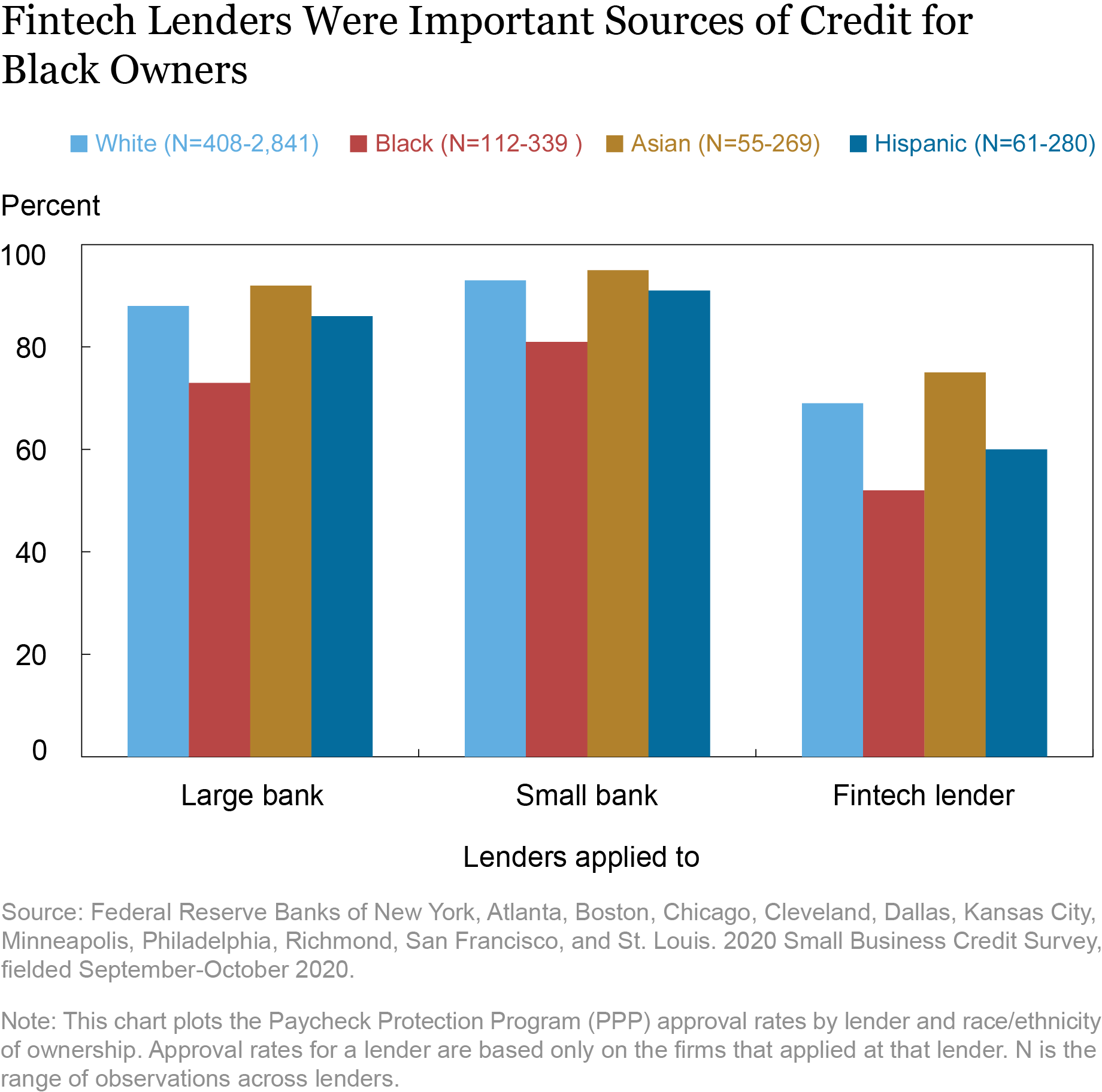

Editor’s note: Since this post was first published, the chart entitled “Fintech Lenders Were Important Sources of Credit for Black Owners” has been updated to reflect a correction in the estimated approval rates of PPP loans. For example, following the correction, we do not find that Fintech lenders approved the highest percentage of applications from Black-owned small employers, as compared to firms owned by persons of other races and ethnicities. (October 26, 2022, 1:08 pm).

Small businesses not only account for 47 percent of U.S employment but also provide a pathway to success for minorities and women. During the coronavirus pandemic, these small businesses—especially those owned by minorities—were hard hit as consumers reduced spending disproportionately on services that require in-person physical interaction, such as hotels and restaurants. In response, the U.S. government launched the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) to provide guaranteed and potentially forgivable small business loans. In this post, we examine financial technology (fintech) lenders participating in the PPP and find that, while disbursing only a small share of total loan amounts, they provide important support to minority business owners, who have in the past been underserved by the traditional banking industry.

Small Business Experience during the Pandemic

The previous post showed that declines and recoveries in small business revenues differed along demographic lines. Survey evidence shows that the number of active business owners dropped by 22 percent from February to April 2020, with Black and LatinX owners suffering most. Industries with a higher concentration of female, Black, LatinX, and immigrant businesses were among the hardest hit. More recent evidence shows that these trends continued until later in 2020 with almost 80 percent of small business firms reporting drops in income with stark disparities by business owners’ race.

Bank and Fintech Lenders in the Paycheck Protection Program

The PPP is administered by the Small Business Administration (SBA), with funds allocated in three rounds or waves. A total of $659 billion in funding was authorized in the first two waves between April 3 (the PPP launch date) and August 8, 2020. In 2020, the PPP provided 5.2 million loans worth more than $525 billion. The current (that is, third) round began in January 2021 with an additional $284 billion in funding authorized, all of which was exhausted by May 4.

Eligibility is broad-based, and different from other SBA lending programs since applicants only have to document their payroll and other expenses and do not have to meet the “credit elsewhere” test. However, they can apply for and receive loans only through eligible financial institutions. Since lenders bear no credit risk when providing loans guaranteed by the U.S. government, differences between lenders in loan disbursements primarily reflect their ability to process applications and their approval decisions.

Initially, loans were mostly distributed by banks, which allowed for rapid delivery but also increased the chance that loans might go to existing bank customers rather than the hardest-hit borrowers. In an important change, the SBA authorized more nonbank lenders to accept applications toward the end of the first wave. Of particular interest are fintech lenders, defined as nonbank lenders that operate online such as Kabbage, Square, Lending Club, OnDeck, and PayPal Working Capital. Recently, fintech companies have become important lenders to small businesses, especially in places where banks have pulled out. Compared to banks, fintech lenders may be more efficient in processing applications (as was shown for mortgages), and more likely to lend to underserved businesses that are unable to borrow from banks.

Who Applied for PPP Loans and from Which Lenders?

Which lenders did borrowers seek out for PPP loans? To examine this question, we use data from the Federal Reserve’s 2020 Small Business Credit Survey, which included 9,693 small employer respondents (firms with 1-499 employees) nationwide and was carried out in September and October 2020. Some firms reported in the survey that they did not apply for PPP loans, mainly because they felt unqualified for the loan or loan forgiveness. Of applicants, 87 percent applied to either a large bank (one with more than $10 billion in deposits) or a small bank, while just 8 percent applied to fintech companies. By comparison, in the previous five years, 44 percent of firms with between one and 499 employees had used a large or small bank and 20 percent had used fintech companies.

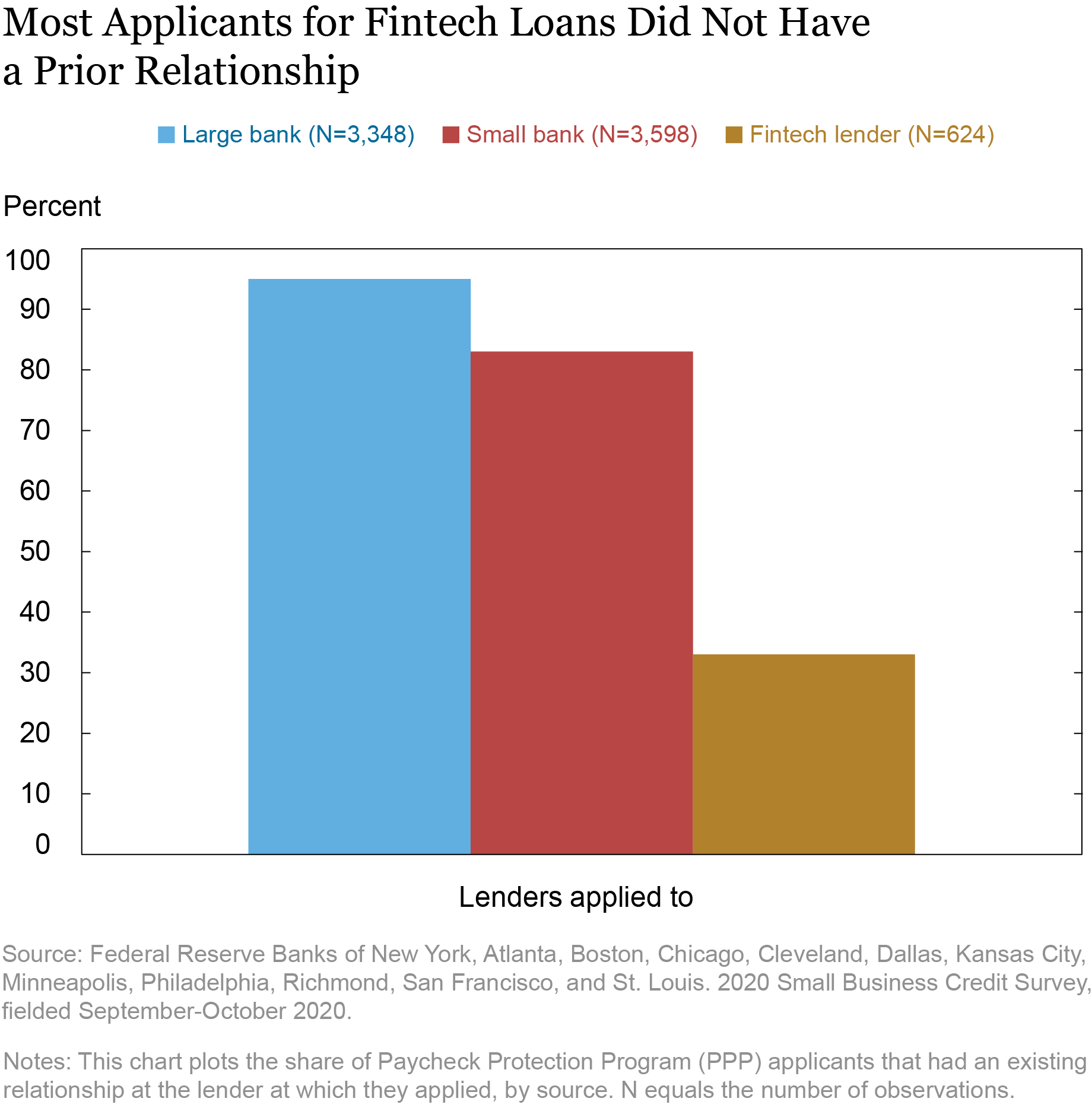

One reason that borrowers might turn to banks is because they have an existing relationship. While that connection may facilitate loan approval and encourage banks to look out for the survival of applicant firms, it may also prevent loans from reaching the hardest-hit borrowers. Indeed, as the chart below shows, 95 percent of large bank applicants and 83 percent of small bank applicants had a prior relationship with their PPP lenders. (Borrowers may have relationships with multiple lenders). These borrowers had more employees, higher credit scores, and were more likely to have white owners. In contrast, just one in three small employers that applied to a fintech lender had worked with that lender before. These borrowers had fewer employees, lower credit scores, greater difficulty in accessing PPP credit, and were more likely to be Black-owned and to have reduced their workforce. Thus, our results suggest that PPP applicants self-select among lenders, with underserved borrowers gravitating towards fintech companies.

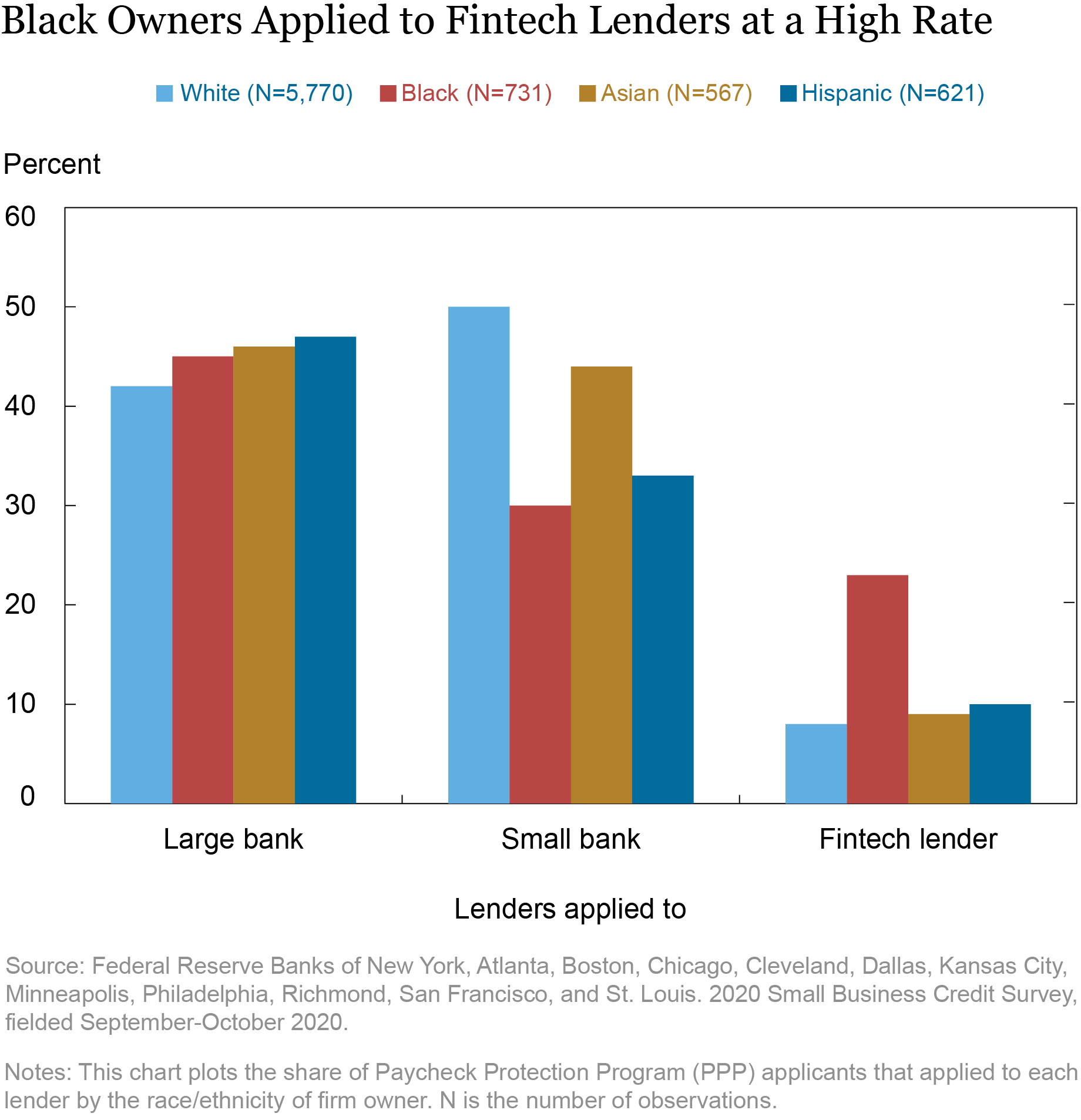

Nearly half of all small employer firms sought out PPP funds from a large bank, with little difference in application rates by race and ethnicity (see chart below). However, there are clear differences in the racial profile of applicants to small banks and fintech lenders. Fewer Black and Hispanic owners applied to small banks than did white and Asian owners. In contrast, about one in four Black-owned firms applied to fintech lenders, more than twice the rate of white-, Asian-, and Hispanic-owned firms.

Who Got Approved for PPP Loans and from Which Lenders?

Did fintech lenders provide credit to firms with Black owners by approving their applications at a high rate? The chart below shows that fintech lenders approved a sizeable majority of their applicants, even though most of their applicants had no existing relationship with them. PPP approval rates were highest at banks, likely reflecting the fact that most of their applicants had existing banking relationships, consistent with prior research.

How Much PPP Credit Did Fintech Lenders Provide?

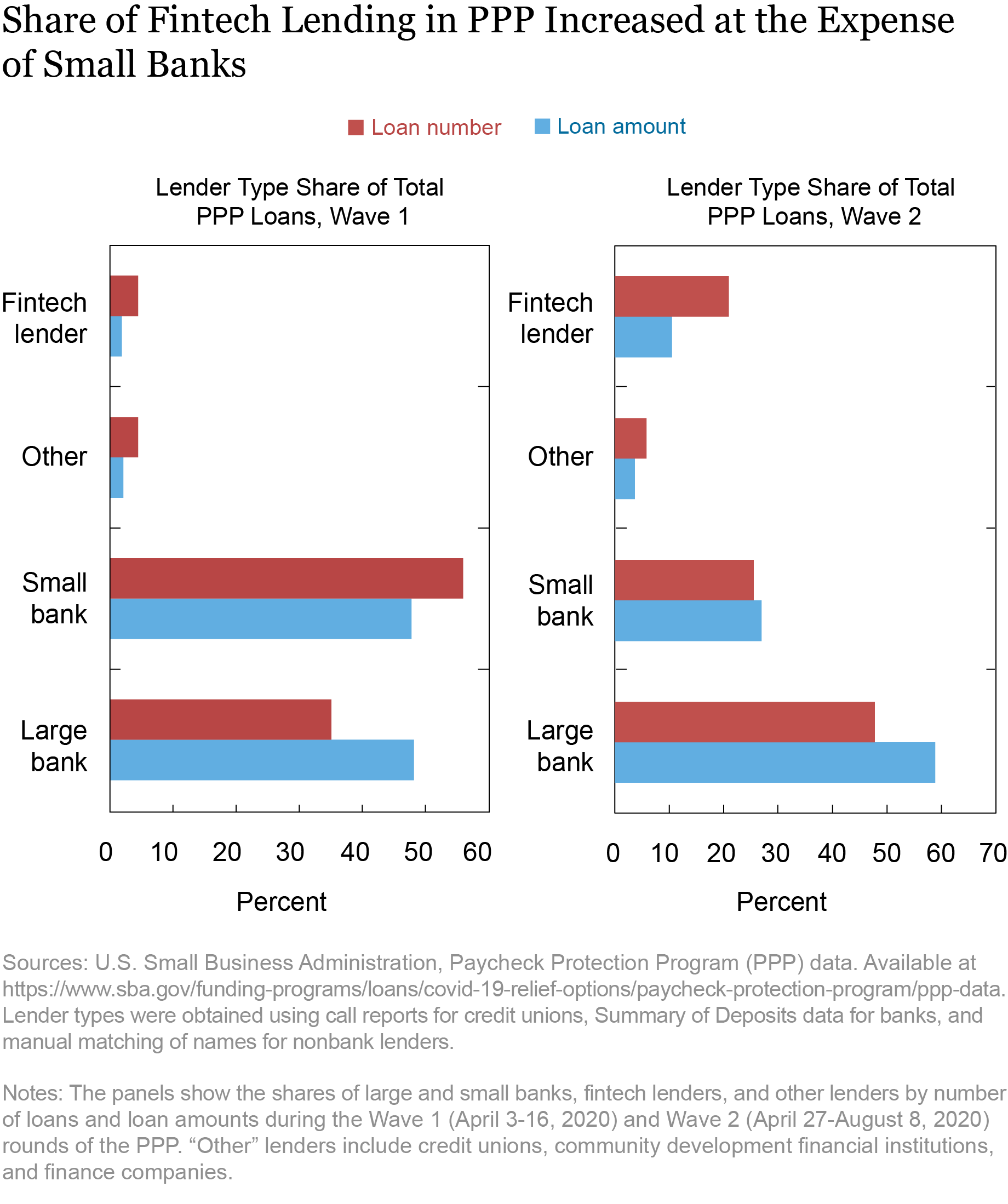

The pattern of PPP loan applications and approvals is reflected in banks’ and fintech lenders’ shares of PPP loan amounts (see chart below). During Wave 1, the fintech share of loan amounts (number of loans) was less than 2 percent (4 percent) as compared to 96 percent (91 percent) for banks, in part reflecting delayed authorizations from the SBA. The smaller share of fintech lenders in the loan amounts implies smaller fintech loan sizes, a topic we explore further in part three of this series. Smaller banks had a greater share by the number of loans than large banks, consistent with anecdotal evidence that large banks initially lacked the capacity to process applications, providing small banks an opportunity to gain market share.

As more fintech lenders were approved as PPP lenders, their share of lending increased to more than 10 percent of loan amounts and 20 percent by number of loans in Wave 2. While large banks maintained their shares from Wave 1 to Wave 2, those of small banks plunged by nearly half. One possible explanation is that fintech lenders appealed to small bank customers by providing a more efficient approval process which outweighed the benefits of having a prior banking relationship. By comparison, large bank customers appear to have continued to value their banking relationships.

Inequality in Credit Access

Although fintech lenders had a small share of PPP loan volumes, they likely served borrowers who would not have received loans otherwise. Applicants who approached fintech lenders for PPP loans were more likely to lack banking relationships, be minority owned, and have fewer employees. Our results suggest that historical factors that prevent Black owners from receiving bank credit continued to operate with the PPP.

In the next post, we examine the implications of unequal credit access: whether smaller firms received the amount of PPP credit that they requested, and whether loans went to the hardest-hit areas and mitigated job losses.

Jessica Battisto is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Outreach and Education Group.

Jessica Battisto is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Outreach and Education Group.

Nathan Godin is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Nathan Godin is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Claire Kramer Mills is an assistant vice president and director of community development analysis in the Bank’s Outreach and Education Group.

Claire Kramer Mills is an assistant vice president and director of community development analysis in the Bank’s Outreach and Education Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jessica Battisto, Nathan Godin, Claire Kramer Mills, and Asani Sarkar, “Who Received PPP Loans by Fintech Lenders?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 27, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/05/who-received-ppp-loans-by-fintech-lenders.html.

Additional Posts in the Series

COVID-19 and Small Businesses: Uneven Patterns by Race and Income

Who Benefited from PPP Loans by Fintech Lenders?

Press Briefing

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics